Philly leaders are demanding money to repair schools in new Pa. budget

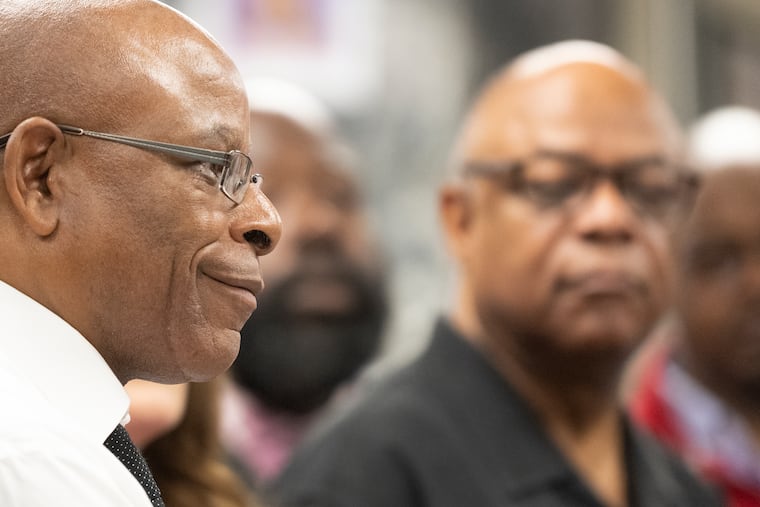

City Councilmember Isaiah Thomas called the district's toxic school buildings "the most urgent problem we have right now in the city."

As negotiations over the state budget heat up, Philadelphia lawmakers and officials say funds to fix the city’s aging, toxic schools rank as a top priority.

At a news conference Friday at South Philadelphia High School, the school district’s superintendent, City Council members and union leaders joined State Rep. Elizabeth Fiedler (D., Philadelphia) in support of a proposal to pump hundreds of millions of dollars into school facilities.

Philadelphia is the epicenter of the state’s school facility crisis. Asbestos contamination closed six district school buildings this year — and some won’t reopen at all this fall. More than 40% of the district’s 216 buildings lack fully functioning air-conditioning, leading to closures on hot days. Overall, the average age of district buildings is 73 years old.

Isaiah Thomas, a City Council member who chairs the council’s education committee, called the state of the school district’s buildings “the most urgent problem we have right now in the city.” He has called for a $5 billion investment in school facilities improvements statewide over the next five years.

Pennsylvania faces a budget surplus this year, presenting a “very unique moment,” Thomas said Friday. “We have an appetite to do something about it.”

Democrats are hopeful about the prospect of new state money for school repairs — a funding stream that has been dormant for years — given Gov. Josh Shapiro’s inclusion of facilities funding in his budget plan.

» READ MORE: Pa. public school advocates are furious at Gov. Josh Shapiro for supporting school choice vouchers

While Shapiro, a Democrat, proposed $100 million for school facilities next year, House Democrats have called for increasing that figure to $250 million.

House Democrats have also moved to restart a state program for distributing money to school districts for facilities projects — advancing a bill that would allow districts to apply for grants covering 75% of the cost of repair projects, with awards capped at $5 million. The program, which could get a vote as soon as next week, hasn’t been funded since 2016.

“We know it’s a first step,” Fiedler said, noting that schools’ capital needs likely total in the billions of dollars.

In Philadelphia, where the district’s capital needs have been estimated at $5 billion, Superintendent Tony B. Watlington Sr. said the district was undertaking 27 projects this summer, including increasing the number of air-conditioners and improving HVAC systems.

“It’s no secret that asbestos continues to be a problem in one of the nation’s oldest cities,” Watlington said, adding that the district was working to identify swing spaces for students at Frankford High School, which switched 900 students to virtual learning in April due to damaged asbestos and is expected to remain closed all next school year.

The Frankford experience taught the district “we must have shovel-ready swing spaces ready to go,” Watlington said. He said the district was preparing a strategic plan that would identify “what should our 21st-century school facilities look like in Philadelphia.”

Jerry Jordan, president of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, said the conditions in Philadelphia wouldn’t be tolerated in whiter, wealthier school districts. A Commonwealth Court ruling in February found Pennsylvania’s school funding system unconstitutional, in part for depriving children in lower-wealth districts compared to more affluent peers.

“We are failing one of our most basic fundamental obligations as a society: keeping our students safe at school,” Jordan said. “We have to prove the worth of our children, and it’s outrageous.”

The disparities aren’t lost on students, said William Sax, a social studies teacher at South Philadelphia High School, who said he’s taught in classrooms where the heat doesn’t come on until noon. Students have taken the standardized Keystone Exams in the cold, wearing coats, he said.

“When you go into a facility that looks like something, you want to learn something,” Sax said. “When you go into a building that doesn’t look like anything, you know what people are saying about you.”