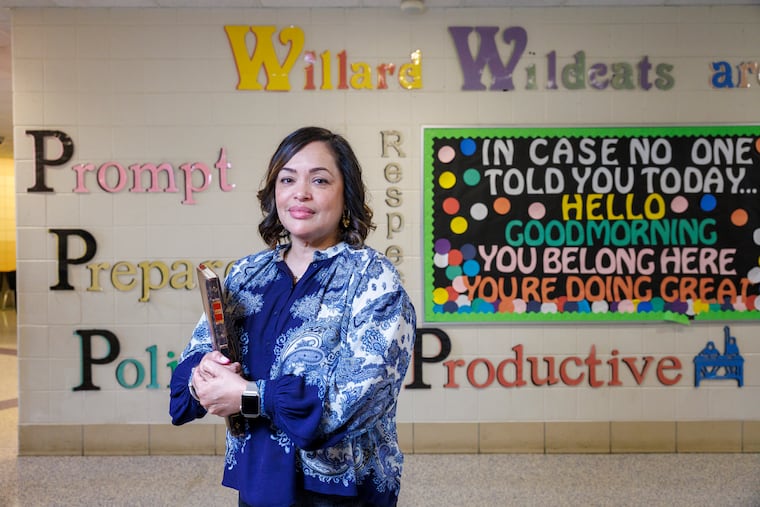

From the child of undocumented parents to a star principal, here’s how this Philly educator thrives at her toughest job

“I respect these children so much,” Willard principal Diana Garcia said. “They walk through what they have to walk through. Some of them don’t have basic needs. But they show up.”

Some people might say Diana Garcia came from very little: Her parents were undocumented immigrants from Dominican Republic who sometimes lacked the money to buy clothes for the family. They never stepped foot in their children’s school buildings — they didn’t speak English, and they didn’t feel welcome.

But Garcia often says she “comes from poverty, not dysfunction.” Despite her parents’ lack of material means, there was abundant love at home, thrift store books — including a set of encyclopedias that had some volumes missing — and the pervasive sense that education would vault their bright daughter to a better life.

» READ MORE: These Philly principals have won 2023 Lindback Awards. Here’s why.

Garcia, now the principal of Willard Elementary School in Kensington, surely has lived up to her parents’ dreams for her.

She is one of seven winners of the 2023 Lindback Award for Distinguished Principal Leadership, a recognition of the Philadelphia leaders who have made significant leadership and humanitarian contributions to their school community. In addition to Garcia, the other winners include Crystal Edwards, W.D. Kelley Elementary; Alphonso Evans, Stearne Elementary; Lillian Izzard, Edison High; Kahlila Johnson, Overbrook High; Amanda Jones, Muñoz-Marín Elementary; and Heather Mull Miller, Hunter Elementary.

“I can relate to a lot of our kids,” said Garcia. “I’ve walked the streets that they’ve walked through to get to school. My message has always been, ‘Your current situation does not dictate your future. If I did it, you can do it.”

Garcia was born in New York, but her family settled in Philadelphia, and she attended public schools in North Philadelphia: Potter-Thomas Elementary, Stetson and Conwell middle schools, and Mastbaum High.

She earned a business degree at Chestnut Hill College, then felt called to the classroom. The Philadelphia School District needed bilingual teachers, and offered a path to certification through a teacher apprentice program.

Garcia never looked back. She landed at the now-closed Ferguson Elementary at Seventh and Norris, and has worked in education in North Philadelphia ever since — as a teacher and principal at district and charter schools.

Early in Garcia’s time as an apprentice teacher, she was clucking like a duck to demonstrate a concept to her students. She looked up to see her principal, Linda Hall, sitting in her classroom, observing. Garcia was terrified — was her unorthodox style OK? — but Hall was delighted, and went out of her way to let Garcia know she appreciated the lengths to which she went to ensure her students understood the material. That made an impression.

“She trusted her teachers, she gave us room. She really found ways to acknowledge us, and she spoke highly of her team. She held us accountable, but she had faith that we” would shine, Garcia said.

That’s the kind of principal Garcia aims to be, too. She can’t talk about Willard without giving a shout-out to her staff — “I just can’t express how indebted and honored I am to work with this team,” she said.

Serving as Willard’s principal is perhaps one of the hardest things she has done in her life, but also among the most rewarding, Garcia said.

The school sits in Kensington, where the city’s opioid and gun violence epidemics touch everything. When she did a cleanup of surrounding streets a few years ago, a single block Garcia cleaned yielded 100 dirty needles.

In September, three people were shot outside Willard, and in March, bullets were fired into two Willard classrooms during the school day. Although no one was injured, the incidents have shaken the school community deeply, Garcia said.

That’s the toughest part of the job: the things from which Garcia and her staff can’t protect their kids.

“We can control deployment schedule, how many folks are at this doorway. But I can’t control what happens down the street, up the block, after hours, in homes,” Garcia said. “We just work hard to send the message that when they’re here, they’re safe.”

Yes, she’s an instructional leader, Garcia said. But a big part of her job is removing barriers for students. So if a family needs beds, or rent money, or food, she finds community organizations to help. On a recent day, a student came to school in slides and socks, inappropriate for the weather and for running on the playground.

So Garcia pulled the child aside and had a private conversation with her. The little girl told her principal she had no other shoes. Garcia headed to a school closet full of donated clothes and shoes, and found her a new pair.

“I respect these children so much,” Garcia said. “They walk through what they have to walk through. Some of them don’t have basic needs. But they show up.”

So do teachers and staff at Willard, where turnover is uncommon.

“Coming here poses a risk, and our teachers understand that, and they’re still willing to come,” Garcia said. “And when you have a staff that understands the population and is committed to ensuring that the kids have a great school experience, the kids rise to the occasion.”

Willard kids know it by heart: When Mrs. Garcia asks, “How do I love you?” they answer, “No matter what.”

Garcia is proud that Willard’s academic stats are headed in the right direction, with academic outcomes and attendance trending up.

But everything flows from relationships, Garcia said.

That sustains her on the tough days, when students act out, reeling from mental-health needs and trauma brought on by things they see in the community, or when there might be a lockdown because of neighborhood activity.

“But the best part of my job is that on my worst day, I’ll get a hug from a kid that just totally changed my demeanor and my life,” said Garcia.