Betsy Ross was buried three times. She’s not the only American with multiple graves.

History has taught us that a person’s burial site isn’t necessarily their final resting place.

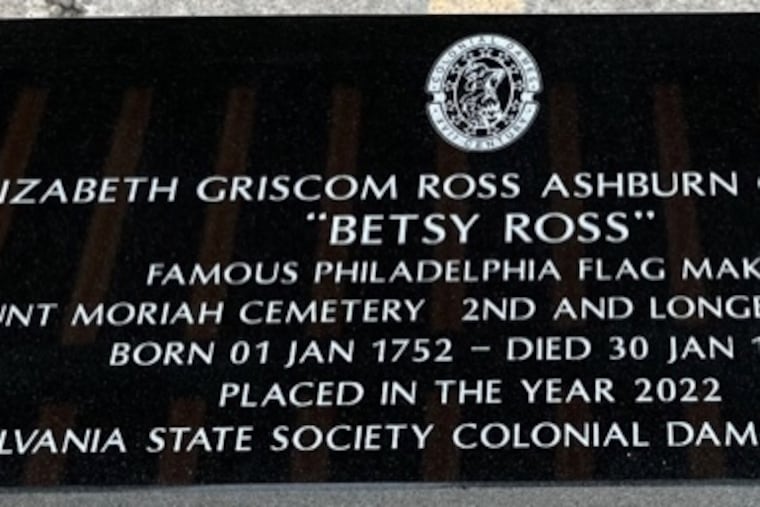

On Oct. 16, a group of women with ancestral ties to colonial America placed a marker in a Southwest Philadelphia cemetery at the second of Elizabeth Griscom Claypoole’s three graves.

They did this knowing that the woman, also known as Betsy Ross, isn’t there.

In her busy afterlife, Ross — who may or may not have sewn the first official American flag — was buried at age 84 in Society Hill in 1836.

She was disinterred in 1856, when her Quaker cemetery was shuttered to make way for city growth. Ross was moved to Southwest Philadelphia’s Mount Moriah Cemetery, a portion of which is in Yeadon.

There, she was reburied without a grave marker, though a cemetery monument was eventually installed in 1923.

In 1975, in anticipation of the Bicentennial, Ross was disinterred once more with her descendants’ permission and finally buried in the courtyard of the Betsy Ross House in Old City, under magnolia trees. Her Mount Moriah cemetery monument was removed and reinstalled at Valley Forge National Park. Neither cemetery nor park officials said they know the year.

Different generations of members of the National Society of Colonial Dames of the XVII [17th] Century placed the markers, both in 1923, and earlier this month.

“We are correcting history — again,” said Buckingham Township resident Marion Lane, state president of the organization. “Without a marker, no one knew Betsy Ross had been there.”

Not surprisingly, as the years went by, it became harder to identify Ross’ remains, which had been buried with her third husband, John Claypoole.

As to what’s inside Ross’ third coffin at the Betsy Ross House, there are several conjectures.

Both Lane and Ken Smith, president of Friends of Mount Moriah, said that in 1975, all that was dug up of Ross’ was a collar bone and a boot.

“Not true!” said Lisa Acker Moulder, director of the Betsy Ross House. “Parts of two skulls and leg bones were discovered. A female was identified by a skull fragment, and a man by the size of a femur.”

Still, suggested Todd Van Beck, funeral historian at the Cincinnati College of Mortuary Science, “Earth burial is an inexact science,” and it’s possible that some of Ross’ remains still exist in the ground at all three of her graves.

History has taught us that a person’s burial site isn’t necessarily their final resting place.

Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson had his left arm buried in Chancellorsville, Va., after it was shot on May 2, 1863, and amputated. Eight days and 100 miles later, Jackson was killed and interred soon after in Lexington, Va.

Abraham Lincoln was entombed, then moved to a space between the walls of his tomb for fear of grave robbers. Years later, when a new memorial was being made for him, Lincoln was transported to an unmarked grave while the work went on. The 16th president was ultimately removed from that site and buried in Springfield, Ill., which he’d considered his true home, according to historians.

In another case of multiple burials, Revolutionary War Gen. “Mad” Anthony Wayne of Easttown Township, Chester County, died of gout and was buried near Erie in 1796. The story goes that his family wanted his remains relocated to Radnor. Twelve years later, the coffin was dug up, only to reveal his body to be nearly intact. It was too hard to transport that way, so the corpse was boiled and the bones were taken to the family plot in Delaware County. Then the cooked flesh was poured into the original grave. Apparently, some bones were lost on the trip to Erie, so it’s possible that Wayne’s remains might be strewn in lots of places. One spooky story holds that every Jan. 1 — Wayne’s birthday — his ghost searches for his scattered skeleton.

Throughout America, the remains of thousands of people have been unearthed and relocated.

In mid-18th-century Philadelphia, it became “fashionable” for some people to relocate the coffins of loved ones to newer, prettier, park-like spots such as Mount Moriah, and Laurel Hill Cemetery in East Falls, said forensic archaeologist Kimberlee Moran of Rutgers University-Camden.

More often, though, if coffins were moved, it was for the sake of progress, as Ross originally was, said Keith Eggener, professor of architectural history at the University of Oregon. To make room for San Francisco’s early-20th-century development, around 150,000 bodies were shuttled out of city cemeteries and into the ground in suburban Colma, historians say.

Sometimes, cities failed to empty cemeteries slated for removal, and construction workers laid foundations over the departed, forever entombing them, Van Beck said: “There are graves of the Revolutionary War dead under buildings everywhere.”

Something like that nearly happened on Arch Street in Old City in 2016, when as many as 300 historic grave sites from the 310-year-old First Baptist Church burial ground were discovered during a residential construction project. The deceased were supposed to have been moved in 1859.

Their remains are being studied by a group of historians, anthropologists, and archaeologists — which Moran is coordinating — and will be reinterred next September at Mount Moriah — perhaps not far from Betsy Ross’s penultimate burial site.

Though Ross’ remains are gone, the newly marked spot will alert visitors that “Mount Moriah is an important part of her story,” Lane said.

It has added significance, said historian Hilary Iris Lowe of Temple University, an expert on the history of women.

“Very few graves of women in U.S. history are visited or venerated,” she said.

As it turns out, Betsy Ross’ burial sites are both.