Philly City Council is considering new requirement for affordable housing

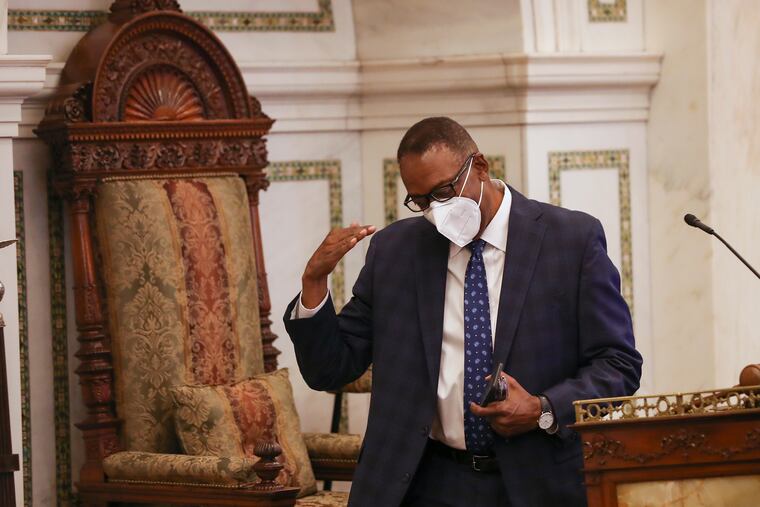

Council President Darrell Clarke wants developers to include affordable units in their big multifamily housing projects in North Philadelphia.

In the midst of an otherwise sleepy autumn City Council session, Council President Darrell Clarke has introduced a bill that would require developers building multifamily housing around North Broad Street to provide units for lower-income residents in their projects.

“There is a significant level of development happening along North Broad Street,” said Clarke, whose district covers that area. “Literally, we’re talking three 400-unit projects. Given the need for affordable housing, we thought this might be the best opportunity to get a consensus on doing something on North Broad as it relates to providing affordability.”

Laws that require developers of new construction to provide housing affordable for people with low to moderate income are referred to as “inclusionary zoning.” Cities throughout the country have experimented with the concept, mostly in areas with super-hot real estate markets such as New York and San Francisco.

Clarke’s plan for the area around North Broad Street would require developers building more than 10 rental housing units to designate at least 20% of them for people at 60% of area median income. That means housing earmarked for those making about $50,000 for a two-member household (allowing a rent of about $1,423 a month).

The bill would also allow for the developer to build units for higher-income residents if they offered for-sale units instead of rentals. The exact rental restrictions would evolve over time to keep up with inflation.

Real estate industry advocates have often criticized inclusionary zoning efforts such as this for adding to the cost of their projects without compensation, creating few affordable units, and discouraging development in targeted areas.

Clarke says that his bill could address some of that criticism with the help of a new state law sponsored by State Rep. Jared Solomon (D., Phila.), called the “Affordable Housing Unit Tax Exemption Act,” which authorizes local governments to establish up to a 10-year tax abatement for the renovation or creation of affordable housing in “deteriorated areas.” If City Council passes enabling legislation, that could allow Clarke to offer abatements to developers who are required to build affordable units under his inclusionary zoning bill — mitigating the costs imposed by that requirement.

Solomon’s bill “allows us to designate certain zones that could potentially provide an incentive — such as a higher level of tax abatement — if the developer agrees to build a certain level of affordable housing,” Clarke said.

Previous attempts at inclusionary zoning

This isn’t Council’s first inclusionary zoning effort. Former Councilmember Maria Quiñones-Sánchez, who resigned earlier this year to run for mayor, unsuccessfully attempted to get a citywide version passed in 2017. At the end of 2021 Councilmembers Jamie Gauthier and Quiñones-Sánchez created and shepherded into law targeted versions of the idea in booming sections of their districts.

Clarke says he’s been intrigued by inclusionary zoning for more than a decade, and a draft version of his bill would have covered his entire district, instead of just the area around North Broad Street.

Real estate development lobbying groups are opposed to inclusionary zoning and argue that Quiñones-Sánchez and Gauthier’s bill have repressed development in the targeted areas. After those laws went into effect in July, only one zoning permit has been issued for four mandatory affordable units as part of a small apartment project in Kensington.

The Building Industry Association, the lobbying group for residential developers, is negotiating with Clarke over his bill. While the group opposes the idea, members applaud the fact that, unlike the two previous bills, Clarke’s bill would also require developers to meet requirements by building units for higher income families. In combination with a possible future tax abatement on projects that include affordable housing, they say his legislation could succeed in its aims.

“We believe that the tax abatement bill that’s out there could be a huge help,” said Gary Jonas, president of the Building Industry Association. “If that gets adopted at the city level, that would be very helpful for actually delivering affordable units.”

The clock is ticking

But no councilmember has introduced enabling legislation that would allow for Solomon’s state law to be applied in Philadelphia. Clarke’s spokesperson had no information on any plans to do so. Solomon says he’s been “working on it” with the Council president’s office. To get the bill passed by the end of this session, it would have to be introduced next week, at the Nov. 17 session.

Some prominent figures in the real estate industry are skeptical that inclusionary zoning can succeed, even if they are granted a tax abatement to include affordable units in their properties. Given the continued heightened costs of construction and sharply rising interest rates, the math just won’t work.

“A ... 10-year tax abatement is a step in the right direction, but that alone cannot be the solution,” said Mo Rushdy, managing partner at the Riverwards Group, a housing developer in Philadelphia. “It has to be in a package of incentives that allows mandatory inclusionary zoning to work. Otherwise, it’s just going to be another bill and get passed with very little results.”