A new fund offers coveted loans to formerly incarcerated people in Philly

The Fountain Fund has just launched in Philly hoping to alleviate barriers to access to capital for returning citizens.

Dealing with financial institutions — banks and credit card companies, Realtors and rental agencies, car dealerships — filled Michael Butler with anxiety.

He knew he’d face an inevitable series of unanswerable questions: Where are your W-2s? Tax returns? Credit report? Job history?

After going to prison at age 18 and serving 17 years, Butler thought his release would mean he was finally free.

Now, at age 39, he’s found he still can’t escape those questions — and neither can others trying to rebuild their lives after prison.

“Life smacks you in the face and says not yet,” said Butler, who helped start a reentry nonprofit and earned the support of District Attorney Larry Krasner while in prison. “It is one of the most feared things that people who are incarcerated coming home have to face: coming to a world, stepping into an institution, and having to explain why they’ve been missing for so long.”

Barriers to capital and finance-based opportunities are one of the most pressing issues faced by about 400,000 Philadelphians with criminal convictions. The Fountain Fund, a Virginia-based nonprofit, has just been launched in Philadelphia to alleviate that problem by offering low-interest loans to formerly incarcerated people.

Banks often look for credit, job, and pay history that many formerly incarcerated people don’t have, effectively icing them out of traditional loan opportunities in some cases.

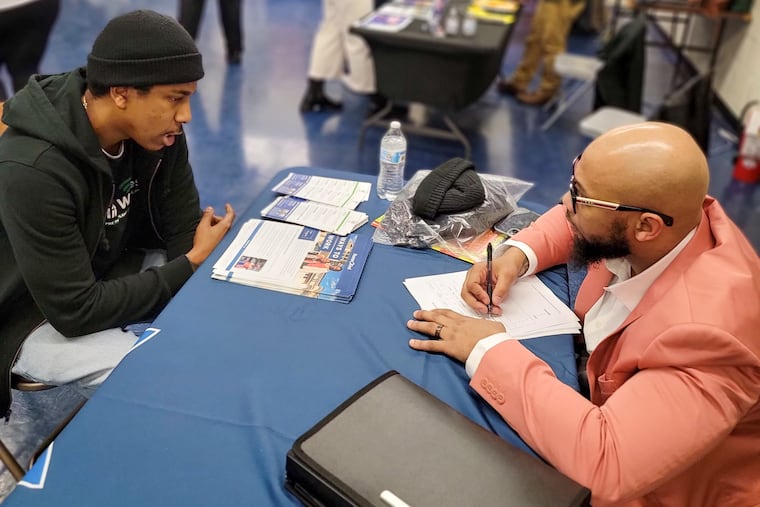

Launched in 2017, the Fountain Fund distributes loans of about $250 to $15,000 alongside financial education for returning people who are already employed, have feasible job opportunities, or have viable entrepreneurial ventures. Anyone who’s been locked up, is working or expects to be working, and can point to ways a loan would improve quality of life qualifies to apply. The nonprofit was launched in Charlottesville, Va., before being expanded to New Orleans, Richmond, Va., and now Philadelphia.

Butler, who said his anxiety about accessing financial resources has often turned into frustration and anger, now works as the Fountain Fund Philadelphia’s director of client and community engagement.

A different organization with a chapter in Philadelphia, the GreenLight Fund, worked to bring the Fountain Fund to the city.

The GreenLight Fund helps identify pressing, unmet needs in different neighborhoods.

“Last year when we ran our selection cycle in Philadelphia,” said Felicia Rinier, executive director of GreenLight Philadelphia, “economic support for previously incarcerated individuals was lifted up repeatedly as a need.”

GreenLight then looked nationwide for existing organizations that could address the issue.

GreenLight invested $600,000 into the Fountain Fund, and another philanthropic partner gave an additional $150,000 to fund the program for the first four years.

Rinier said the program expects to give loans to as many as 50 people in year one, and to 450 people by its fourth year. It will be located inside the Center for Employment Opportunities, another GreenLight-funded organization that helps returning people get jobs.

Fountain Fund offers loans with a 5% interest rate, and a 3% interest rate for people who enroll in automatic payments. The group’s financial coaching helps teach formerly incarcerated people to build credit and learn about entrepreneurship, and Butler said participants can get incentives such as a 10% rebate off their loan and a savings account if they attend extra sessions.

Butler, who was incarcerated for third-degree murder, has worked on reentry issues with Krasner since his release, along with other city initiatives, including the Institute for Community Justice. He said he still expects to face stigmatization for the rest of his life, and is now throwing his energy behind the Fountain Fund’s effort.

“It’s not just about giving out money,” Butler said. “It’s to educate people about money, to keep them away from, possibly, bad habits that they could fall into.”

According to a 2022 report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics that looked at more than 50,000 people released from prison in 2010, about two-thirds of them were jobless at any point over the four-year period. One-third were unable to find a job at all over four years, and the average employed person held more than three jobs over the four-year period, which the Prison Policy Initiative said suggests lack of gainful employment.

Eighteen percent of Fountain Fund loans have been used to start or expand a business, according to the organization’s website, allowing people to bypass the exclusionary job market.

The loans have gone toward other things, too, according to a study of the 300 formerly incarcerated people who have received some of the more than $1.5 million in loans since the fund was launched.

The average returning person comes home, said Rinier, with about $13,000 in court fees and fines, which makes it difficult to get a driver’s license reinstated or buy a car. The Fountain Fund said about one-third of loan recipients used the money to help cover those kinds of expenses, and more used it to purchase vehicles or get housing.

Upon his release from prison, Butler said, he had a network of people to offer support.

“I’m just glad that I’ve had great people in my life help me through those processes,” Butler said, “and I feel like the Fountain Fund is going to be that for people stepping inside of our doors.”

The Philadelphia Inquirer is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push toward economic justice. See all of our reporting at brokeinphilly.org.