The Boy in the Box was just the beginning. A new team is tackling dozens of Philly’s other nameless murder victims.

Solving the backlog of Philadelphia’s cold cases is up to one team. It’s low on resources.

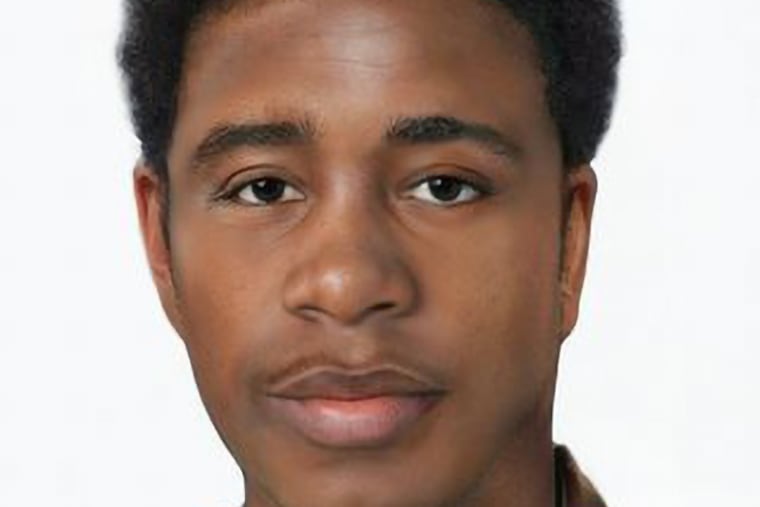

The youth, found shot dead along Cobbs Creek Parkway, was old enough to have a tattoo with the initials HB or BH inside a heart on his arm, yet too young for his wisdom teeth to have grown in.

He stood 5-foot-9, weighed 139 pounds, and his hair had a Jheri curl. He was wearing worn acid-washed jeans. In their February 1989 report, police wrote that he could have been a New Yorker with the nickname Dallas.

Thirty-four years later, his real name remains a mystery.

Since 1955, Philadelphia’s list of anonymous dead has grown to 225, according to NamUs, a federal database of people who are dead and unidentified, including 15 who died last year. The majority were men, and more than half were Black, when race could be determined.

They include a newborn found in a creek in 1997, a young Black girl found decapitated in a milk box in 1962, and a man found shot next to railroad tracks along Delaware Avenue in 1977.

Sixty-eight people were found in vacant lots or homes. Almost 60 more were found washed upon the banks of or pulled from the city’s rivers.

Now a collaborative team from the Philadelphia Police Department, Medical Examiner’s Office, and District Attorney’s Office is taking a new look. Team members have 30 separate investigations underway, though they did not say which cases they were investigating, or if the young man found in 1989 was among them.

“We’re giving people back their names,” said Ryan Gallagher, Criminalistics Unit manager at the Police Department’s Office of Forensic Science.

He convened the group of experts after police had success last year using DNA testing to identify the Boy in the Box, a 1957 child homicide case, as Joseph Augustus Zarelli. The Inquirer earlier this month confirmed the identities of his parents, both now dead.

» READ MORE: The biological parents of the ‘Boy in the Box,’ Joseph Augustus Zarelli, have finally been identified

But the team’s efforts are limited. Its members are actively investigating only deaths that appear to be homicides, about 10% of the backlog, and cases where the cause of death is unclear.

Nearly 200 others — suicides, accidents, overdoses — are not receiving their scrutiny right now. These cases are the responsibility of the Medical Examiner’s Office, but the city’s chief medical examiner, Constance DiAngelo, says her office is short on the staff and equipment needed to address the backlog. They don’t even have the ability to scan fingerprints into a database for identification without the help of police, she said.

Exhuming the past

Family members in recent years have resorted to pleading on social media sites like Missing in Philly, used to help people find loved ones, frustrated by the Police Department’s slow response.

“This absolutely sickens me to post but I need help finding my sister.”

“My brother Joe has been missing from the Manayunk area since 2019.″

“Please help me find my friends daughter’s father his name is Reuben Wray last seen Thursday January 5th leaving Temple Hospital with a head injury...”

Some may be found alive, or identified, or never end up before the city’s new work group, due to its limited scope.

When the group started, authorities pored over records, looking for possible matches between the Police Department’s missing persons list and the medical examiner’s tally of unidentified dead, though none so far have been confirmed.

Investigators also sought out DNA samples for the cases they’re working on. If none are available, the team may seek to exhume a body, though that has not been necessary so far, Gallagher said.

Forensic genealogy uses a person’s DNA sample to identify family members, even distant relatives. It has allowed millions of people to use commercial databases like Ancestry and 23andMe to trace their family history and is increasingly being used as a tool to solve cold cases.

But applying forensic genealogy to cold cases can cost $7,000 to $8,000, Gallagher said.

While the Police Department has so far funded each request for forensic testing, the work group is in the process of applying for grant funding. Gallagher’s 30-person department is about a third of the size needed to handle the massive amounts of specimens that come in for DNA testing.

» READ MORE: ‘Boy in the Box’ case brings hope DNA could help identify Philadelphia’s hundreds of nameless dead

Any newly deceased unidentified person in the city has DNA samples taken and submitted to public databases.

The potential to find a relative is still limited. For example, most of the DNA samples in the public databases come from white donors.

“We need the Black and brown and Asian communities to submit samples,” DiAngelo said.

The work group plans to host a missing persons day this spring where Philadelphians can add their DNA samples to existing databases.

When a death isn’t a crime

When there are no signs of a crime, the Medical Examiner’s Office takes the lead in investigating an unidentified death in Philadelphia. When searches of police databases don’t work, they may take descriptions of the deceased to health centers or homeless shelters to try to identify the person.

Two cases were recently identified after relatives filed a missing persons report, or called the morgue.

Last year, more than 500 people who died could not be immediately identified, more than any year since 2017, according to data provided by the office.

Many of them were unhoused, said Jamie Willer, a Medical Examiner’s Office investigator participating in the collaborative group. She is increasingly called to investigate deaths in Kensington.

“They’re a lot harder to ID,” she said, saying people’s identifying information can be stolen and those who knew them may be reluctant to talk.

In cases where bodies have decomposed, busts or forensic reconstructions may help to create a likeness of the person’s face, Willer said, but authorities are not currently taking this approach due to a lack of funding.

The members of the newly formed forensic team must balance work on older cases with the city’s more recent drownings, falls, murders, and overdoses.

“I feel like this team is going to be together for a while,” DiAngelo said.

This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Jamie Willer’s name.