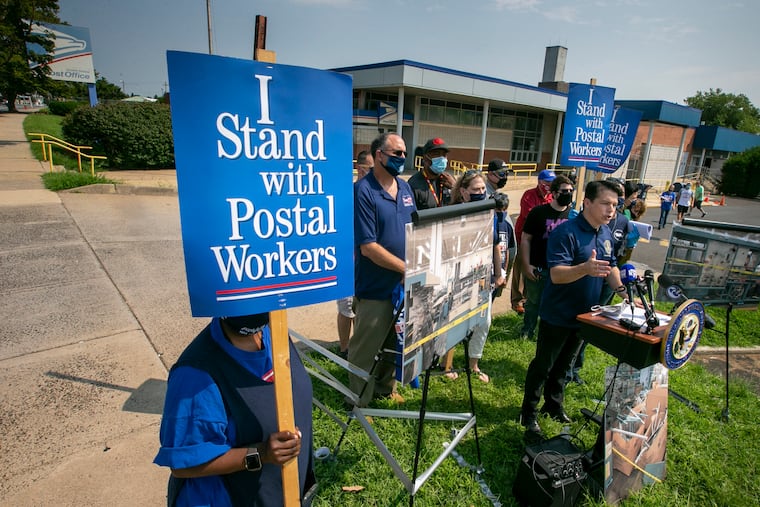

The head of the USPS said he was suspending changes. But Philly mail delays aren’t getting better

Philadelphians are still going days without mail. And workers and experts say the Postal Service’s problems run deeper than just the new policies.

The Postmaster General said earlier this month that he was suspending some planned operational changes, making at least a partial retreat amid growing criticism that the Trump administration is undermining the U.S. Postal Service in a bid to hobble mail voting in the presidential election.

But that hasn’t solved pervasive mail delivery problems across the Philadelphia region. At least a dozen mail sorting machines have been removed from USPS processing centers across Southeastern Pennsylvania in the last two months, union leaders say — that damage has already been done.

And while Postmaster General Louis DeJoy pulled back on additional changes, the main policy in effect that is causing delays across the country remains unchanged, union leaders said. Philadelphians are still going days without mail. And workers and experts say the Postal Service’s problems run deeper than just the new policies.

Staffing remains unsustainably low, the product of longtime issues exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. And while overtime pay has been restored, DeJoy’s enforcement of a policy that orders carriers and delivery trucks to leave for their posts on time, whether they have all their mail or not, remains in place.

In his Aug. 18 statement, DeJoy said he was suspending additional cost-saving measures — which had included removing mail sorting machines, and cutting post office hours — “to avoid even the appearance of any impact on election mail.”

But he didn’t address the changes that had already been made. DeJoy, a major campaign donor to President Donald Trump, later said in Senate testimony that machines that have been removed won’t be put back. A USPS spokesperson did not respond to questions about whether the delivery policy, which has resulted in dozens of bins of mail being left behind, will be reversed.

Union leaders said that most of the machines have already been disassembled and sent to scrapyards.

But the main factors contributing to the mail delays aren’t the removal of machines, which has generated headlines and anxiety across the country, union leaders and post office experts said. The focus on the reduction in machines also obscures the fact that machines were already being cut over the years, as mail volume decreased long before the pandemic.

More direct culprits, they said, are DeJoy’s policy that delivery trucks and mail carriers must “leave mail behind” if it’s not sorted by the time their shifts begin, along with widespread staffing shortages — caused by a lenient pandemic leave policy, poor retention, and widespread coronavirus cases. Those have combined to create a backlog that sometimes grows faster than it is delivered, workers say.

‘Months away from being efficient’

DeJoy did reinstate overtime, which has helped Lehigh Valley offices catch up on deliveries, said Andy Kubat, president of the regional postal union.

Still, residents across the Philadelphia area continue to report days- and weeks-long delays.

Testifying before a U.S. Senate committee, DeJoy said that in Philadelphia, the “intimidation of the coronavirus” has been the main problem. He said the average availability of Postal Service employees has dropped about 4% nationwide due to the pandemic. But in urban areas like Philadelphia, where at least 143 employees have contracted the virus since March, employee attendance is down more than 25%, he said.

The Postal Service also extended its leave policy in April to allow 80 hours of emergency paid sick leave and up to 12 weeks of leave for family or child-care emergencies, which has contributed to more employee absences.

Joe Rodgers, president of the National Association of Letter Carriers Keystone 157 in Philadelphia, said the Postal Service failed to hire much-needed carriers before the pandemic. It’s trying to hire now, but the jobs are specialized and physically taxing, which makes it difficult to retain employees and teach them quickly.

“We are months away from being efficient,” Rodgers said.

Leaving mail behind

Massive USPS machines scan and sort hundreds of thousands of letters based on delivery routes. The sorted items are then placed into bins, which truck drivers bring to the designated post offices for carriers to deliver.

In the past, if a machine was running behind schedule, the Postal Service would allow the trucks to wait, or dispatch additional drivers. In a recent report, the agency’s Office of the Inspector General said this is generally because managers “prioritized high-quality service above the financial health of the Postal Service.”

But DeJoy, a former logistics executive who has sought to improve the agency’s dire finances, saw this as a shortcoming that led to unnecessary overtime. Upon his appointment in June, he ordered trucks and carriers to leave on time. That meant, he acknowledged in his Senate testimony, “some mail got stuck on a dock.”

A 2019 order had mandated that trucks leave on time, but was routinely ignored until recently, with USPS logging more than 590,000 late trips across the country in the second half of 2019, including more than 13,000 from a Philadelphia distribution center, according to a Postal Service report.

DeJoy cited an estimated $1 billion in annual savings in defending the trucks order before Congress.

“It is really a farce to sit here and believe that we can do nothing,” DeJoy said this month at a Senate hearing.

Postal employees said the wait time and extra trips are worth it to ensure people get their mail on time.

“When you have a truck leaving empty because the machine has to run for another 10 minutes, wouldn’t it be better to wait 10 minutes and take it all at once?” Kubat said.

‘Trash in a box’

Eight delivery bar-code sorting machines and one flat sorting machine have been decommissioned from Philadelphia’s Processing and Delivery Center, one of the largest such plants in the country, said Nick Casselli, president of American Postal Workers Union Local 89 in Darby. Casselli said scraps of metal parts are sitting in boxes on the floor of the Lindbergh Avenue facility.

“It just looks like trash in a box,” Casselli said. “We have more empty spaces on the workroom floor right now than we do machinery.”

Three machines have been removed from the Lehigh Valley Area’s processing plant, Kubat said.

“One has been thrown away, and two are disconnected just sitting in parts on the work floor,” he said.

The dismantling of the letter-sorting machines has only slightly contributed to the delays seen across Philadelphia this summer, as the volume of letter mail has substantially dropped, Casselli said. But he worries that once businesses and schools reopen, mail will pick back up, and existing delays could be exacerbated.

Data reports to the Postal Regulatory Commission show that dozens of machines have been decommissioned in recent years based on volume and productivity, but the speed and amount that have been decommissioned this year is unprecedented.

A memo obtained by the Washington Post showed that the USPS planned to decommission 671 letter-sorting machines, or about 10% of its inventory, this year as part of a long-term plan to adjust to the declining use of letter mail. By comparison, 125 machines were decommissioned in 2018, and 186 were taken offline in 2019.

Staff writer Harold Brubaker contributed to this article.