A Philly success story: Celebrating winning sports teams is more fun in a walkable city

“That’s the great thing about an old, dense city. People want to celebrate in public places."

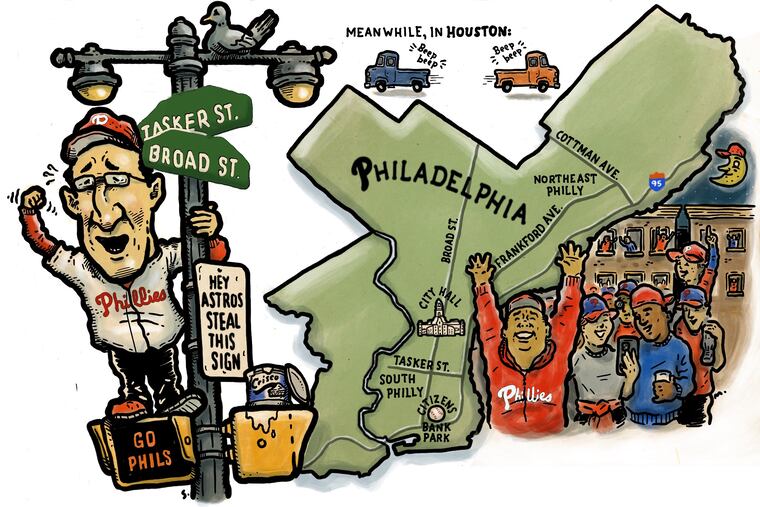

As the victorious Phillies flooded the field at Citizens Bank Park on Sunday, the streets of South Philadelphia, Center City, and Northeast Philadelphia sprang to life as well.

All along South Broad Street, clusters of fans took over street corners to celebrate. Champagne bottles were popped, rally towels whipped with superhuman vigor, and a cacophony of whoops and shouts echoed through blocks of neatly kept rowhouses. At Broad and Snyder Streets the light poles had been preemptively greased to deter overeager fans from climbing to life-threatening heights.

“There were fireworks and lots of chanting — it was just a really great vibe,” said Claire Jaffe, who lives in South Philadelphia and partied hard at Broad and Oregon Avenue, where crowds dominated the usually car-clogged intersection.

“As I walked home, I really enjoyed the little pockets of people outside bars and homes that had just organically come together,” Jaffe said. “You could get caught up in different parties as you go along.”

The phenomenon wasn’t confined to South Philadelphia. On Sunday, columns of revelers also wended their way toward City Hall, where authorities closed much of Broad Street to cars as pedestrians claimed the thoroughfare for their celebration. At Frankford and Cottman Avenues in the Northeast, the intersection was closed to traffic and transformed into a jubilant mob scene.

Philadelphians are hoping for more such ecstatic street scenes as the Phillies embark on the World Series Friday and the so-far undefeated Eagles nurture Super Bowl dreams.

Such are the joys of cheering on a team’s win in a walkable city where people can easily get together — without driving — and take over the street. Not the kind of celebration one could expect in San Diego or Houston, cities wreathed in highways, where pedestrians are a rare sight.

‘People want to celebrate in public places’

“That’s the great thing about an old, dense city,” said Paul Goldberger, an architecture critic and author of Ballpark: Baseball In the American City. “People want to celebrate in public places. Whereas highways and automobile-oriented arterial roads don’t feel like public places in the same way.”

Philadelphia isn’t unique, of course. Pittsburgh was thronged after the Penguins won the Stanley Cup in 2016 and 2017. Baltimore saw its share of street celebrations in 2013 when the Ravens took the Super Bowl, and Washington turned out (though more decorously) for the Capitals’ victory in 2018.

But all these cities have dense urban centers, with populations that have been recently growing in the core and its adjoining neighborhoods. Cities that boomed after the era of automobile dominance that began in the 1950s, especially those in the Sun Belt, tend to have more attenuated downtowns, with smaller populations, and little pedestrian access to surrounding areas.

The sprawling developments that have dominated American cities, and most of its postwar suburbs, do not lend themselves to spontaneous street celebrations or public interaction of any kind.

John Ricco was watching the game Sunday with his family in Lower Bucks County. When the Phillies won, the cheering in their house was intense, but outside it was just another quiet night in suburbia. Then he took SEPTA’s West Trenton Line back home to his apartment in Center City, where a far more riotous reality awaited.

“I went from the sleepy suburbs where it was my family and I celebrating to literally thousands of people congregated in the street to celebrate right outside my apartment,” said Ricco.

Ricco notes that many people were augmenting their adrenaline rush with a healthy (or not) dose of booze, which would also be a disastrous combination with a more auto-oriented landscape. To get to the town center near his parents’ house, he would have had to drive for over 10 minutes — not something he wished to do after consuming a few beers with his dad.

“After people are boozed up, they’re not going to go driving,” Ricco said. “Even if they did try to drive to a spontaneous thing with this, how would that work? Where are you going to park?”

Philly’s sports fan culture

Philadelphia’s street-party atmosphere after big wins is also, of course, attributable to the near lunatic fan culture. Then there’s social media. The outrages and joys of the festivities after the Phillies’ World Series win in 2008 and the Eagles’ Super Bowl victory in 2018 rocketed around the internet and won notoriety for a city that already revels in its rascally reputation. (Who can forget the horse-poop eating incident?)

On Sunday night, though, it was hard to not be impressed by the way the city itself added to the sheer scale of the street parties. On almost every corner of Broad from Oregon Avenue to City Hall, there was at least a small group of revelers enjoying the night together. The crowd at Frankford and Cottman put even their comrades outside City Hall to shame. Camaraderie was in the air, along with a not-inconsiderable amount of firework smoke and toilet paper.

For Philadelphia residents like Ricco and Jaffe, this is part of why they want to live in the city. Not specifically because of occasional bouts of crazed communal bacchanalia, but because they feel like a part of something bigger than they might in newer suburbs or in a sprawling Sun Belt city.

“The way Center City is makes people feel physically and emotionally connected to the city,” Goldberger said. “That dovetails perfectly with the idea of celebrating a sports team.”

Like a World Series champion, perhaps?

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article incorrectly spelled the name of Claire Jaffe. The error has been corrected.