Philly Puerto Ricans join latest swell of organizing activity for political influence here and on the island

The 40 Philly residents met at Taller Puertorriqueño, one of more than 50 assemblies that have sprouted up across the country — three in New York City, one in Florida, dozens in different municipalities in Puerto Rico.

It was Saturday afternoon and 40 Philly Puerto Ricans had gathered in a room taking turns at the mic to discuss the issues facing a population with a complicated relationship to the United States: its citizenship status, the economic oversight of the island, people’s health, and endless corruption among elected officials, to name a few.

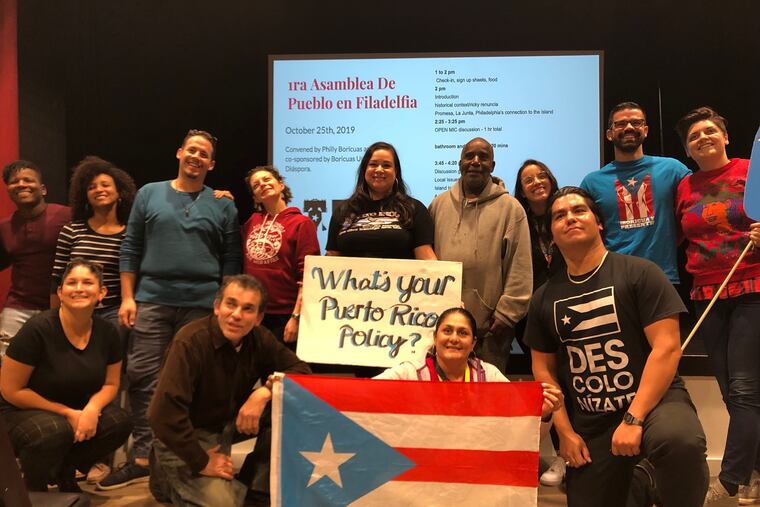

This was the inaugural People of Puerto Rico Assembly, headed by Philly Boricua, a recently formed political education group to organize locals on how to make an impact here and on the island.

The Philly residents met at Taller Puertorriqueño, one of the more than 50 assemblies that have sprouted up across the country — three in New York City, one in Florida, dozens in different municipalities in Puerto Rico — in the aftermath of the political turmoil that caused Gov. Ricardo Rosselló to resign after a series of corruption scandals.

Puchi DeJesús, a member of Philly Boricua, said the group’s end goal is to educate the communities about their weighty voting power and how to exercise it. Not only do Philly Puerto Ricans, who make up 62% of the Latino population here, have the numbers to make a difference in local elections; they have the additional capacity to elect U.S. politicians who then can influence policy regarding Puerto Rico.

“The residents of the city of Philadelphia are very aware that Puerto Ricans are here, and that they have been here for generations," DeJesús said, "but they do not see them as a political force to make changes inside and outside the city, because we have to activate ourselves.”

Adrián Rivera Reyes, once a candidate for City Council at large and a member of Philly Boricua, said the group invited local residents and leaders of old and new activist groups to have a discussion defining its political priorities and coming up with strategies to enact them.

Reyes noted the many federal policies that are oppressive toward Puerto Rico: for instance, La Junta, the controversial board responsible for restructuring the debt and overseeing the negotiation of creditors.

Puerto Ricans living in Philadelphia in particular are doubly burdened, paying taxes for a struggling school system and having to financially help family on the island, the group said.

“So, perhaps the most important thing is to develop an educational campaign to be able to use that power that the Puerto Rican people have in the United States," Reyes said, "which is the right to vote for people who are making decisions toward the nation and the island.”

But Puerto Ricans aren’t just holding meetings. They are also confronting people in power in public spaces to address the issues that the nation has dealt with for the last 120 years, including the Jones–Shafroth Act, which continues to regulate how goods enter the island and Puerto Rico’s crippling financial debt (not to mention corruption surrounding the hurricane relief efforts after Maria and Irma in 2017).

Last month, former New York City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito was one of seven people arrested during a protest that disrupted the reopening of the Museum of Modern Art after a temporary closure for renovations and expansions. They were demanding that the museum cut ties with trustee Steven Tananbaum, who runs a hedge fund that has purchased a large amount of Puerto Rican government debt. In Puerto Rico, taxpayers are obligated to pay off its high-interest debt before any money goes toward such services as health and education. The result is that those services are often starved of funding.

Closer to home was David Lagarza, who was expelled from a conference room at Rutgers University-Camden last month, after he publicly shamed the resident commissioner of Puerto Rico, Jenniffer González-Colón — visiting the university to discuss Puerto Rico post-María — for supporting the Trump administration.

Fermín Morales Ayala has been a community leader in Philly since the 1990s to advocate for the freedom of political prisoners and for the U.S. Navy to evacuate the Puerto Rican island of Vieques. He’s heartened to see Philly Boricua and a younger generation rising to power at such an important moment in Puerto Rico’s history.

The new leaders today, he said, are not distracted by internal strife — such as sexual orientation, skin color, and racial identity — and are joining together regardless of political affiliation. The legacy leaders in Philly and on the island had “such a hard time” organizing people because many didn’t understand the terms of being a commonwealth, he said.

“Seeing youth follow this path of us, who have fought for a long time, makes me feel very good," Ayala said, "because the contemporary struggle continues with a more advanced, more conscious vision.”

Among the group’s current activities: educating people about the campaign contributions made to Cory Booker, Pete Buttigieg, and Amy Klobuchar by hedge fund manager Seth Klarman, who opposes forgiving Puerto Rico’s debt. Philly Boricua also is in the process of surveying 1,000 Philly Puerto Ricans to learn more about their needs and willingness to get involved in organizing.