Olympic breakdance might be on the horizon. Is Philly’s scene ready for the competition?

The International Olympic Committee is considering breakdancing for the 2024 games in Paris. In Philadelphia, hip hop’s second city, many breakers wonder how the judges would measure their groove.

The breakers made their way to the circle. Out on the floor at the Gathering, many had already gotten started.

Michael Cannon, 28, hadn’t really been planning on dancing as he did that night at Philadelphia’s longest-running hip-hop party. His knees had been bothering him and grew swollen, but all the same, he couldn’t help himself. Dance, the Germantown native explained, is really about the emotion, and he was moving off the feeling.

Cannon, who dances with Philly Surfers, isn’t convinced that the proposal to make breaking an Olympic sport is a good idea, because he’s not sure how that kind of spirit would be measured.

“Our founding fathers laid down a foundation for us that was supposed to be based off of us knowing our curriculum, and studying things like that,” he said, wiping sweat off his face (the Gathering doesn’t have AC). “Not off us laying down moves to be judged upon. Because the judge doesn’t always know what the heart feels.”

For months, the breaking world has brimmed with anticipation. The International Olympic Committee begins its 134th session Monday and may approve breaking — provisionally — as an official sport for the Summer Games in Paris 2024. The Youth Olympics last year in Buenos Aires already welcomed breaking, something Olympic watchers viewed as a test run.

Along with waves of excitement, the Olympic process has stirred debate, and in some cases, distaste from such dancers as Cannon. Despite the potential prestige, the moment has raised questions over whether the Olympic stage is right for Philly dancers, even among those who say they’re in favor. Conversation in the breaking community, which grew decades ago out of hip hop party culture, roils with concerns over how the art would be judged, who would get to decide, and ultimately who, in a playing field expanded long ago with hip hop’s globalization, would benefit from Olympic glory.

Raphael Xavier, a longtime Philly-based breaker with roots in Wilmington, isn’t against Paris 2024 per se; he just thinks that Olympic elevation could make the global community implode.

“Everybody’s still arguing about what it is, what it’s not," he said. "Is it a dance? Is it a sport? Who created what? How come this person is not getting the attention?”

Hip hop scholarship has a tendency to follow the music, rather than the dancers, he said. Without clearly traced histories, who’s to tell the next generation what the rules should be?

“No matter how they see it right now," he said, "it’s still some internal beefs that are happening that won’t allow it to move in the [right] direction.”

One layer of controversy concerns breaking’s governance. If accepted, breaking would be the first Olympic “dance sport.” This current campaign falls under the dominion of the World Dance Sport Federation, headquartered in Lausanne, Switzerland. Some breakers resent the fact that the biggest decisions would be up to an organization known for ballroom dancing.

Jean-Laurent Bourquin, a World Dance Sport Federation senior adviser, acknowledged that they could have tried supporting a new, breaker-led organization. But that, he said, would have brought decades more of red tape.

“It would mean that breaking could have been in the Olympics in 2040, for example,” Bourquin said. “We have no time to waste for the new generation that is just coming and who is dreaming to be in Paris or in Los Angeles [in 2028]. I think what people do not realize is that, OK, we could have let the breaking community start in its own way, but they would have gone through many fights between the U.S. and Europe, between the U.S. and Japan, between Korea and Japan, between China and France. And it would have been painful without a concrete result.”

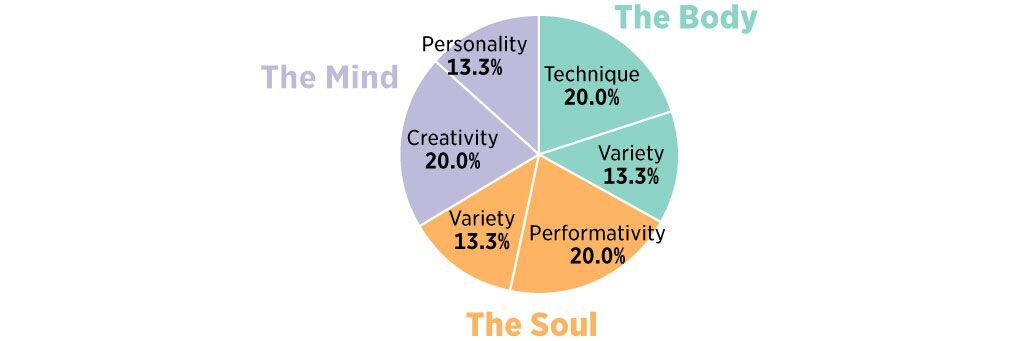

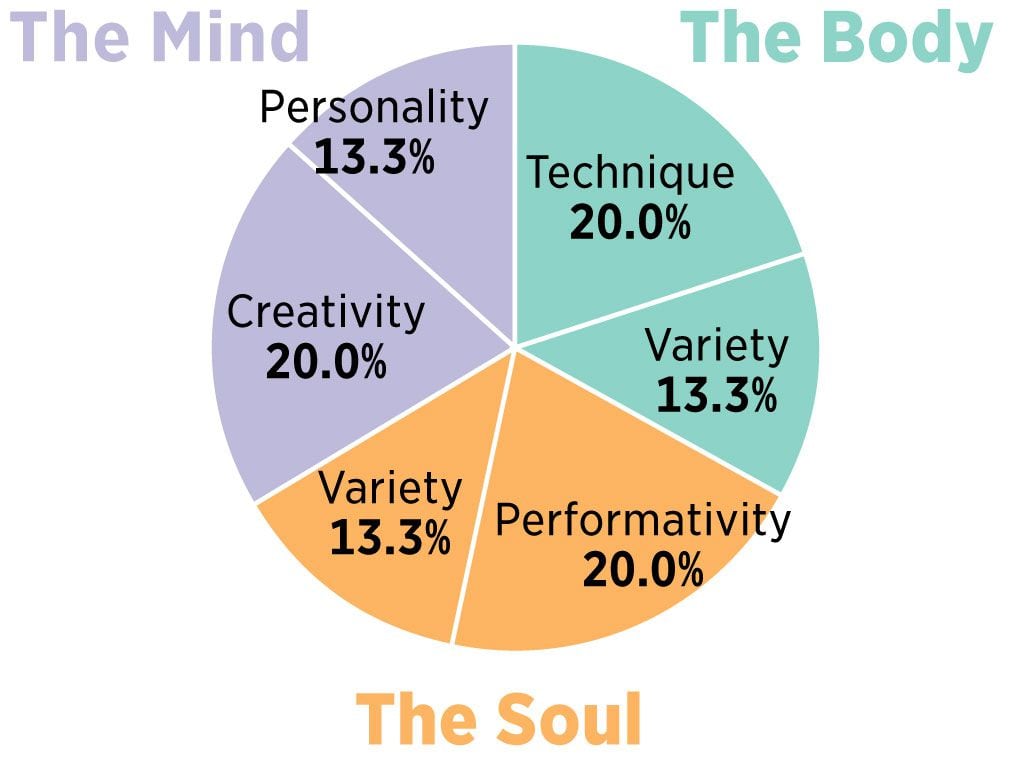

A Breakdown of the Trivium Value System

This is the judging system for the World Dance Sport Federation, which would govern Olympic breakdance, if accepted. Developed by two respected figures in European breaking, its rules mandate that five judges score dancers with each battle round on six criteria, under the categories of body, mind, and soul. In many battles currently, it's common to see judges vote by simply pointing to the winning side. The goal of Trivium, according to a World Dance Sport Federation representative, is to provide more transparency. The federation first implemented the system in the 2018 Youth Olympics in Buenos Aires.

Steve “Silverback” Graham, the founder of both the Silverback Open, a prestigious annual international competition held in Philly, and the nonprofit Urban Dance and Educational Foundation, said he’s working to get more breakers a seat at the table. He calls this Olympic process a blessing and a curse.

The federation, he said, is “going to need the work with the scene. And they are. But on the other hand, they’re not going to be very interested in turning over what I would call bona fide contractual control to the breakers of their own destiny. That’s not going to happen.”

Concerns aren’t just about who gives the medals and how, but also about who could benefit financially through potentially millions in corporate sponsorships, media broadcasts and streaming, tickets, and memorabilia.

Competitive breakdance already has sponsors, training, and conditioning regimens. But with the Olympics, it could be more and different.

Before judging the Red Bull BC One Cypher in Philadelphia last month, Antonio “Knuckles” Chanza, who dances with the crew RepStyles and lives in Northern Liberties, said he could envision a new “whole ecosystem of teaching.”

Xavier, a lecturer in dance at Princeton University, wonders where the top incubators will be, using an elite gymnastics gym as comparison.

Many sources stamp the origin of breaking (the term that dancers prefer over breakdance) to black and multiracial Latinx Caribbean communities in New York in the 1970s. Princeton hip hop scholar Joseph Schloss writes that breaking culture reflects a melding of black American and Caribbean musical and cultural sensibilities that point to a “more Afro-diasporic approach to dance.”

The global spread of breaking tracks with the commercialization of hip hop culture. J. Lorenzo Perillo, a global Asian studies professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, notes that dance, like music, also spread through American imperialism. Some researchers argue that the dance often maintains hip hop expression, like a lingua franca, but welcomes other traditions as it travels. Body accents may shift not only internationally, but also regionally and within America’s diverse breaking circles.

Competitive breaking, on a wide scale, got its start in 1990 in Hanover, Germany, with the international competition Battle of the Year.

Brandon “Peace” Albright, 50, a pioneering b-boy who still works as a touring dancer, said that Philadelphia’s scene came into its own in the early ’80s, with dancing in skating rinks and near the Clothespin at 15th and Market.

Asked to describe Philly’s style, dancers regularly used similar language. Philly breakers come with raw energy. They love musicality; their styles are more soulful. They pride themselves on just having that jig, on listening, on reacting.

Joshua “Supa Josh” Culbreath, 28, of Cobbs Creek, who placed second at Red Bull BC One Cypher’s Philadelphia stop, competes through full improvisation. “It’s not a competition between me and the dancers,” said Culbreath, a dancer with both the crew 360 Flava and Puremovement, the company of legendary Philly breaker Rennie Harris. “It’s a competition between me and how the music moves me.”

Albright, who founded the company Illstyle & Peace Productions, believes that competition-style breaking has drifted too far from its foundation, in favor of a series of nonstop power moves, or gasp-worthy aerials, rather than a fluid combinations of dancerly moves. A lot of Philly breakers feel similarly.

Last month, Macca Malik, 31, won the women’s side of Red Bull BC One’s U.S. Finals in Houston. She’ll represent the U.S. in world finals this coming fall. In her attitude, she’s always repping Philly.

“For me, it’s always a mission to show that style, dance, character, living in the moment, the connection to music — that all of that can still win in these big competitions,” said Malik, a West Philly native who lives in Atlanta. “I feel like if we have that mindset, go out there and do what we do, and just do it to the fullest then cannot deny it.”

Cannon sees a difference between vying for a medal and battling in hip hop culture: “Our art of hip hop was [meant] to unite each other, not tear each other apart.”

Fitting black dances into competitive formats can be difficult, said Thomas F. DeFrantz, a Duke University expert on African American dance. Combat at that scale isn’t really what those dances are about.

“We’re trying to hold each other up. And hold each other,” DeFrantz said. “You won the battle, but it’s only the battle. It’s not the war. It’s never been the war.”

Timothy Hopewell, 17, learned breaking at the Southeast Asian Mutual Assistance Associations Coalition’s Hip Hop Heritage after-school program at South Philadelphia High School. He isn’t all the way against Olympic competition. But for him, the dance is more than dozens of air flares.

“The only major downside that I would see is what I would refer to as the deforestation of hip hop and breaking culture,” Hopewell said. “Losing the heart and soul of what it means to break. Losing the heart, the sauce. That would be the biggest con because breaking literally came from nothing.”

Staff photographer Timothy Tai and staff videographer Raishad Hardnett contributed to this article.