Northeast civic group lives to fight another day but with insurance 12 times the previous cost

The Northeast Philadelphia community group will pay thousands of dollars for insurance that used to cost hundreds.

The Greater Bustleton Civic League will live to fight another day, or at least another year.

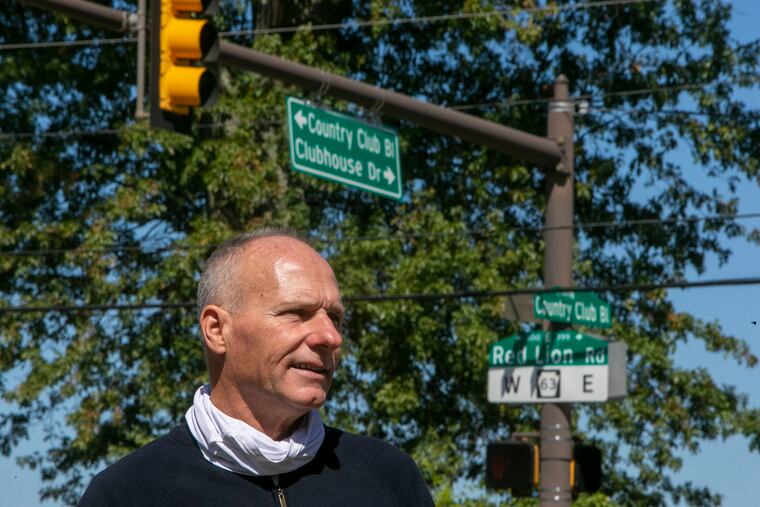

The Northeast civic group got sued in January by the Commercial Development Corp. — a St. Louis-based industrial interest — after tenaciously fighting the company’s plans to open a large warehouse on Red Lion Road.

The Greater Bustleton Civic League (GBCL) then lost its directors and operators insurance, which reimburses legal defense costs for the organization’s leadership. (The previous plan will still cover the group’s costs in this lawsuit.) League president Jack O’Hara went to 21 providers to seek new insurance but was repeatedly denied.

One provider asked for a premium of $25,000 a year, up from the $450 the group used to pay. O’Hara told members the group would likely have to disband.

Finally, on the 22nd call, O’Hara found a company, Nexus Underwriters, willing to insure the group. The terms are much less favorable than they used to be. The former plan had a $450 premium with a $1,000 deductible. The new plan has a $5,584 premium with a $10,000 deductible.

“I feel fortunate we were able to find it and then fortunate that we have this money in the bank,” said O’Hara. “We don’t have much more, but we can cover this and keep $10,000 for the deductible in the account. We’re still alive.”

The GBCL is a registered community organization (RCO), the official designation given in the city’s zoning code to some neighborhood groups. The GBCL gets its funding from its membership, although O’Hara says that it has received donations from elsewhere in the city — and an offer from a Central Pennsylvania philanthropist — after an Inquirer article about the legal peril ran in mid-June.

The code requires developers to meet with RCOs before they bring cases to the Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA) or if projects are being considered by the city’s advisory Civic Design Review committee.

O’Hara and many other neighborhood leaders argue that the city should indemnify against lawsuits these neighborhood groups, which have been given a semiofficial role to play by local government.

The GBCL is based in a middle-class neighborhood and has the resources to afford insurance even at these elevated rates, but many community groups represent lower-income neighborhoods where coming up with almost $6,000 a year would be prohibitive. As a result, many RCOs operate without any insurance, leaving their leaders vulnerable to lawsuits from vengeful business interests.

But Philadelphia government decided against indemnifying the groups because they feared that taxpayers would wind up on the hook for potentially irresponsible actions taken by RCOs.

In the GBCL’s case, the city government and the ZBA agreed that the warehouse developer’s plans were within the site’s zoning. The community organization disagreed, but its case has been dismissed by both the zoning board and the Court of Common Pleas.

The developer’s lawsuit argues that the group is contesting the company’s permits to try to kill the project through delay ”solely for the purpose of … thwarting its development plans.”

Some observers have argued such cases are exactly why the city cannot afford to pay for insurance for community groups.

It’s one thing to protect a neighborhood group for opposing a developer who is trying to build beyond a site’s zoning. But what about being forced to defend community groups who are accused of extorting developers or filing nuisance lawsuits?

“The city didn’t want to indemnify RCOs when it had no voice in how they operated,” Gary Jastrzab, former head of the Planning Commission, told The Inquirer.

Other major Northeastern cities, such as Washington and New York, have organized their neighborhood groups as a more official part of city government, which both protects them from liability and makes them more accountable.

Advisory Neighborhood Commissions in Washington are run by neighborhood leaders who have to be elected and are given a small budget by the city. As an official part of local government, they also cannot be sued, just as the city cannot be sued under the sovereign immunity doctrine that protects municipal leaders from lawsuits that aren’t brought under federal laws such as the Right to Know Act or the Civil Rights Act.

Philadelphia’s system is much looser, without strong accountability measures for RCOs or protections for them against lawsuits from deep-pocketed foes.

That leaves civically engaged community leaders in a difficult position.

“Luckily, we have this money, but after this year, it’s going to be an annual challenge,” said O’Hara. “This lawsuit created everlasting damage.”