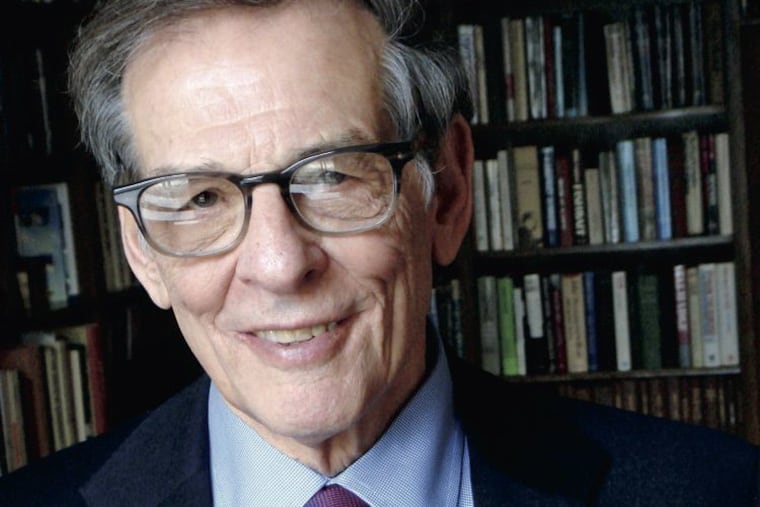

LBJ biographer Robert Caro is ‘Working’ on finishing his final book, he really is

The Pulitzer-winning historian takes time out from his monumental biography of Lyndon Johnson to write a slim volume about his work methods. He wants to write an autobiography after he finishes the LBJ series, but he admits it's a stretch.

NEW YORK — Robert Caro has a new book.

No, it’s not that book.

It’s not the fifth and final volume of The Years of Lyndon Johnson, the monumental Pulitzer Prize-winning series Caro embarked on more than 40 years ago.

The fourth Johnson book, The Passage of Power, covering LBJ’s transition to the presidency after the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2012.

It set the table for the closing volume, chronicling Johnson’s achievements in creating the social welfare programs of the Great Society while he was also sending hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops to Vietnam to fight in a land war that split America apart.

During an interview at his spartan office-apartment near Central Park, the 83-year-old author promises the closing volume will present Johnson finally “fully revealed in all his complexity.”

Waiting with bated breath are fans like former President Barack Obama, who presented Caro with the National Humanities Medal in 2010 and told him that The Power Broker, the 1975 epic about New York “master builder” Robert Moses, shaped his thinking about political power.

Another fanboy is Conan O’Brien, the TBS talk show host who told the New York Times last year that Caro was the most sought-after guest to elude him in 25 years of interviews. O’Brien will finally talk to his favorite author in Los Angeles this month.

O’Brien and other acolytes eagerly anticipating the conclusion of Caro’s sweeping narrative about acquiring and using political power will have to wait at least a little longer, however.

That’s because Caro’s new book is a diversion, a break in the action. It’s a slim volume by Caro’s standards — a mere 207 pages — called Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing (Knopf, $25).

Working takes the reader inside Caro’s dogged, determined approach to research and reporting, a devotion to “turn every page,” as an editor advised him when Caro was a go-getting investigative reporter at Newsday in the 1960s. He has lived by that mantra ever since.

On a bright Manhattan morning, Caro is dressed in a tie and sweater, having walked to his solitary workplace from the nearby apartment where he lives with his chief researcher, his wife Ina, whom he married the day after he graduated from Princeton University in 1957.

A Smith Corona Electra 210 typewriter is on his desk. He bought 17 of them when the model was discontinued in the 1980s and still has 11 left, thanks to readers who send him old ones. He uses a computer for research, but first drafts are written on white legal pads, and then he types up pages on elongated paper, triple-spaced to allow for editing and literal cutting and pasting.

Legendary Knopf editor Robert Gottlieb, who is four years Caro’s senior and who has also worked with Toni Morrison, John Cheever, and Bob Dylan, is still his editor. So far, he’s put down 392 pages of the fifth LBJ book. “I’ve written a lot,” he says, “but there’s still a lot to do.”

“When I was a reporter, I hated having to write a story when I still had questions to ask,” he says. Working on a narrative that is really about the history of the country Johnson came to lead has required lots of time.

And Caro has taken it. One Working chapter is called “Why Can’t You Do a Biography of Napoleon?,” a question Caro’s wife, who has written two travel books about French history, asked when told that for research purposes they were moving to the Texas hill country where Johnson grew up. (They stayed for three years.)

Working talks about Caro’s research for The Power Broker, when he set about telling the stories of the residents — more than a half million —- displaced by Moses’ construction of a highway across the Bronx. Caro writes, “I had never, in my sheltered middle-class life, descended so deeply into the realms of despair.”

“To really show political power,” he writes, “you had to show the effect of power on the powerless, and show it fully enough so the reader can feel it.” To that end, Caro and his wife are soon headed to southeast Asia to understand more fully the impact of Johnson’s policies, not just on Americans but also on the Vietnamese people.

Asked about the root of the empathy in his work, Caro is at first at a loss. “It didn’t come from how I was brought up,” he says. “My mother got very sick when I was 5 and died when I was 11.”

Then a thought occurs.

“The great figure of my youth was Jackie Robinson,” he says. “I was born in 1935, and he was called up to the Dodgers in 1947.” Caro, who grew up on the Upper West Side, would take the subway with his classmates to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn and move down near the third base line to watch their hero up close.

Caro excuses himself to fetch a copy of Master of the Senate, the third Johnson book, published in 2002. There’s a passage he wants to read aloud to better bring the popular hero who inspired him as a boy to life.

“Even if you were white, when you saw the bat held high and then whipping through the ball,” he reads, “when you saw the speed on the base paths, and when you saw the dignity with which Jack Roosevelt Robinson held himself in the face of the curses and the scorn and the runners coming into second base with their spikes high, you had to think at least a little about America’s shattered promises.”

“I don’t know where it comes from,” Caro says about the compulsion to write about the powerless as well as the powerful. “But this was important to me.”

Caro is in excellent health since surviving a bout of pancreatitis in 2003. He says he never planned for the Johnson series to take so long. In 2001, he told The Inquirer that he hoped to be finished with it in three or four years.

Now, he admits he is still several years from finishing. He has hopes to write a full-length memoir after it’s finished. But as a realist and an octogenarian, he’s willing to acknowledge he may never get to that full-length autobiography. "I can do the math,” he says with a laugh.

There have been many junctures in his writing life when Caro has realized that thoroughly reporting an aspect of his story would add months, or even years, to the project. He says each time, he’s said to himself, “I’m not going to do this, the book’s taking too long. But then I keep thinking, ‘You should be doing this. This is what you should have in the book.’ I don’t seem to have a choice. I can’t go on without doing it.”