Rutgers, Penn take steps to confront ties to slavery on their campuses

Rutgers will place historical markers on campus showing how it earliest benefactors built their fortunes through slavery. A Penn group unveiled an augmented reality app that highlights ties to slavery

As part of continued racial reckoning, Rutgers University and the University of Pennsylvania are taking steps to educate the public about ties to slavery on their campuses.

Rutgers said Tuesday it plans to erect four historical markers on its New Brunswick campus that show how the university’s earliest benefactors, including the university’s first president, Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh, and New Jersey’s first governor, William Livingston, built their fortunes through slavery.

“These markers are an invitation for us to talk about the complicated legacies of namesakes and the complicated ways in which blood money from slavery is woven into old institutions like Rutgers,” president Jonathan Holloway said in a statement before presenting the plan to the board of trustees.

Holloway, who is the first African American president in Rutgers’ 254-year history and author of a book that examines Black history, said the new markers will help Rutgers confront its past while looking for ways to move forward.

“History is often troubling,” he told the board. “But I think mature institutions who are confident in who they are in the present can handle and withstand telling stories about their past.”

The effort comes as more colleges around the country are recognizing their painful pasts, a movement underway even before the police killings of Black people last year brought an outcry for racial justice and the pandemic pointed to disturbing racial inequalities.

» READ MORE: Princeton strips Woodrow Wilson’s name from school, citing his racist past

At Penn, a team of students, staff, and a professor last week unveiled an augmented reality app that allows people anywhere in the world to visit six sites on campus and learn more about the university’s ties to slavery. At one point, users hear 2015 Penn graduate Breanna Moore recount how her ancestors were enslaved by a Penn medical school alum and how African Americans’ lives over centuries have continued to be detrimentally affected by slavery. It took two centuries for someone from her lineage to attend an Ivy League institution, she points out.

“We’re at a 200-plus year deficit and to get anything close to what resembles an even playing field is going to require larger efforts to implement reparatory justice initiatives,” she said during a Zoom webinar last week where the app was discussed.

» READ MORE: Penn installs 16-foot sculpture of a Black female figure at entrance to campus

Moore is part of the Penn & Slavery Project, a student team that has been working since 2017 to illuminate how Penn benefited financially from and contributed to slavery. Another stop highlighted on the app shows how 10 of Penn’s 39 residential houses in the quadrangle are named for slave owners and how the university received donations from slave owners. Others tell the histories of the first African American medical practitioner educated at Penn and an enslaved person named Caesar who worked on the campus. And another discusses Penn medical school’s historic ties to scientific racism.

» READ MORE: Penn to remove statue of slavery supporter

Penn provost Wendell Pritchett, who attended the meeting, praised the work of the students.

“It’s important that we embrace the past, understand it and work to atone for it,” he said.

Moore, a Penn doctoral student in history, called on Penn to do more and noted how institutions such as Georgetown University have taken steps to spend money on health clinics, schools, and other programs that would help descendants of enslaved people who were sold to financially benefit the university.

The Penn team originally planned to make the app available only to campus visitors. But because of the pandemic, the team decided to make it accessible to people anywhere, said history professor Kathleen Brown.

Brown said she hopes the app will help people realize that slavery reached even in Northern cities.

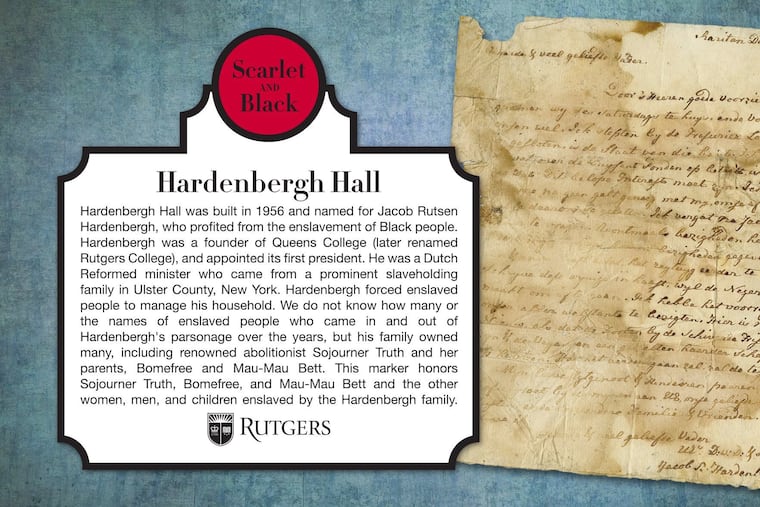

At Rutgers, the metal plaques, which were recommended by a committee as part of the Scarlet and Black Project, which researched and uncovered Rutgers’ ties to slavery, will be installed on campus in the spring.

One will be placed at Hardenbergh Hall, which was built in 1956 and is currently a six-story residence hall on the College Avenue Campus. Hardenbergh, a Dutch Reformed minister, forced enslaved people to work in his home, the university said.

“We do not know how many or the names of enslaved people who came in and out of Hardenbergh’s parsonage over the years, but his family owned many, including renowned abolitionist Sojourner Truth and her parents, Bomefree and Mau-Mau Bett,” the marker will say.

Two other markers will highlight the pasts of two former trustees. Eight other markers are in the works, including one for Rutgers’ founder, Colonel Henry Rutgers, the son of a family who owned slaves.

History professor Deborah Gray White noted that the Rutgers campus does not have statues of Confederate generals or Jim Crow ideologues.

“But its statues, its buildings, and the names around campus venerate men whose wealth was built on the sale of Black people and their free labor,” she said. “The faculty and curriculum at Rutgers endorsed and taught ideas of Black inferiority throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th century. ... This is an acknowledgment of Rutgers’ past, which is meant to strengthen it as it goes forward.”