Fatal shooting of pregnant woman points to trend of violence against women in Philadelphia

"At one time women and children were considered safe ... It isn't like that anymore," said a cofounder of Moms Bonded By Grief.

Terrez McCleary saw the news of one of the latest shooting victims in Philadelphia and started to cry.

She didn’t know the woman or her family, but McCleary’s 21-year-old daughter was murdered and every time she sees another homicide, she thinks of the pain. When it’s a woman who is killed, it hurts her even more.

“At one time women and children were considered safe. We were off-limits,” said McCleary, 52, and cofounder of the group Moms Bonded by Grief. “It isn’t like that anymore.”

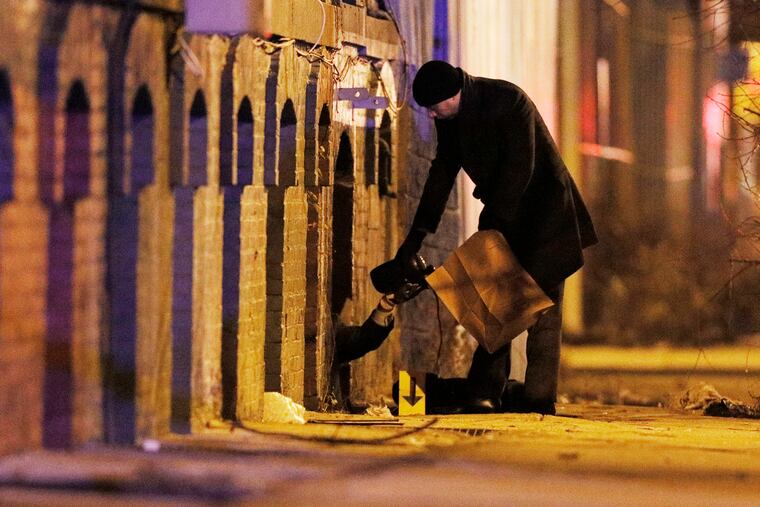

On Friday, a pregnant woman was fatally shot while in a vehicle on Ninth Street between Dauphin and York Streets and, after doctors performed an emergency C-section, her baby died, too. Her identity has not been revealed by police, who have described the woman as being in her 30s.

Relatives of shooting victims and advocates said Saturday that if a pregnant woman can become a casualty of the city’s soaring gun violence, then no one is safe.

More than 500 children have been shot in Philadelphia since the beginning of 2015. While most of these children are between the ages of 13 and 17, Friday’s shooting reminded residents of the recent young victims like 10-year-old Sameje O’Branty, who was shot walking home from school; 11-month-old Yazeem Jenkins, who was shot while sitting in a car; and 2-year-old Nikolette Rivera, shot at home while in her mother’s arms.

Last year, 138 women were wounded or slain in gun violence in Philadelphia. In 2017, that number was 90.

“I think the code of the street has changed,” said Melany Nelson, the executive director of Northwest Victim Services.

Each time a shooting happens, especially ones that involve children, politicians, activists, relatives of victims, and city residents cry out for the violence to end. Then there’s news of another homicide.

In a statement on Friday night’s shooting, Mayor Jim Kenney said he was also grieving this “tragic loss.”

“I want Philadelphians to know there is no more pressing issue for our administration than addressing the scourge of gun violence impacting our communities, and we are doing everything we can to address it,” Kenney said.

Amelia Pagan, an aunt of Nikolette Rivera, said it’s hard to have a sense of safety when hearing about bullets that seem to be indiscriminately hitting women and children. When her 16-year-old son and 17-year-old daughter leave their home near the Nicetown neighborhood of North Philadelphia every day, she worries. She tells them to be vigilant. Still, she’s always scared.

“What happened with my niece, it happened in her home. Inside her home,” Pagan said. “It’s not even in a selected area of the city now. It’s just everywhere."

Through Friday, 180 people had been shot in Philadelphia, a 15% increase from the same period last year.

Hearing about the shooting of the pregnant woman, Yullio Robbins thought: “Oh God, not again. Please, please, help us, help us, help our families. We need help in Philadelphia.”

Robbins, 60, of West Philadelphia, had been trying to mentally prepare herself for Sunday, the fourth anniversary of her son James’ murder. It is still unsolved. When she sees news like that of the pregnant woman’s shooting death, it puts her back to that “dark place.”

Philadelphia’s new police commissioner, Danielle Outlaw, an Oakland native and the former chief in Portland, Ore., stepped into her new role Feb. 10 leading the 6,500-member department in a city battling record levels of gun violence that it hasn’t seen since 2010.

Though Outlaw could not be immediately reached Saturday, she previously told The Inquirer she wanted to bring “a level of urgency” to combating gun violence. She mentioned the city’s plans to implement a new strategy this spring called group violence intervention, which refers to focusing law enforcement resources on a small population of potential offenders. When asked about specifics, she said: “It’s Day Three."

“I am very confident that in some period of time, in a very short period of time, I will have conducted an assessment of some kind, so we can roll something out,” she told The Inquirer.

» READ MORE: Paralyzed gunshot survivors bring their stories and struggles to City Hall | Helen Ubiñas

Families of gun-violence victims had pleaded Thursday at a special committee hearing for City Council members and Outlaw to help them. They held signs with pictures of their children who were killed and appealed for the Police Department to solve murders that have remained unsolved for years.

“Crime is our No. 1 issue by far,” Councilman Allan Domb said Saturday, repeating what he said two days earlier at the gun-violence hearing in City Hall. “This is not an area we should cut back expenses on. We need to go forward and make sure we have the best of everything. The most important thing in anyone’s life is their safety.”

Every time a shooting happens, Aleida Garcia, 61, of South Philadelphia thinks about what the next 48 hours will be like for the affected family. She thinks of how relatives will be notified that their loved one is dead. (Garcia was at work when she heard about her son.) Then, a parent, partner, child, or another relative will go to the coroner’s office to identify the body. Then comes the funeral.

“You crumble and the world just falls down around,” Garcia said. Her son Alejandro Rojas-Garcia was murdered in 2015. On Saturday, she was thinking of Friday night’s shooting and how horrible it would be to see the mother and baby in a coffin.

Garcia had been in the front row at Thursday’s gun-violence hearing. She feels a responsibility to bring attention to the issue. That has included founding the National Homicide Justice Alliance.

“There’s a sense or urgency amongst survivors that this is a crisis,” Garcia said. “This retraumatizes us, but it also makes us want to continue to fight."