Newspaper ads placed by former slaves seeking missing relatives to be read on stage at Villanova

A cast of 75 will bring to life the voices of mothers searching for their children, husbands for their wives, daughters and sons for their parents, siblings for each other.

The plea is poignant in its urgency, a time-is-running-out appeal published in a Baltimore newspaper more than 40 years after Emancipation.

Ann Whaley, 101, is searching for relatives sold away from her. Before she dies, she wants to see them.

“I am very anxious to get in direct correspondence with them,” she writes. "Anything you can do for me, an ex-slave, will be highly appreciated.”

The beseeching words that Whaley penned — part of her letter that appeared in the Baltimore Sun on Aug. 26, 1911 — are about to reach a new audience. On Monday, they will be read from a stage at Villanova University as a cast of 75 area residents and students bring former slaves’ published petitions to life in “Last Seen: Voices From Slavery’s Lost Families.”

The 8 p.m. performance at the school’s Vasey Theater will be a compilation of classified ads, letters, and articles printed in newspapers in the decades after the 1863 signing of the Emancipation Proclamation: mothers searching for their children, husbands for their wives, daughters and sons for their parents, siblings for each other.

“You think of Emancipation as this magic wand of freedom," said director Valerie Joyce, chair of Villanova’s theater and studio art department. "But 50 years after, [families] are still placing ads for the people they lost” in a “search that reveals the open wounds that were left long after slavery ended.”

The production (the tickets are free but have been snapped up already) was born of an online database created in 2017 by Judith Giesberg, a history professor and Civil War scholar at Villanova, and Margaret Jerrido, archivist for Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church in Society Hill.

Their project, “Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery,” has since become a repository for nearly 4,000 ads from hundreds of newspapers, including African American publications such as the Black Republican in New Orleans, abolitionist papers such as the Liberator, and the Christian Recorder, the official organ of the A.M.E. denomination published at Mother Bethel. The materials offer a trove of names of former slaves and long-lost relatives, owners and traders, and plantation locations.

Every state, Canada, and the West Indies are represented. Some searches stretch to Europe and Africa. The project has fueled school curricula and art competitions.

The database, which continues to grow as more ads are transcribed, has been a boon to the keepers of family histories. The Rev. Dr. Mark Kelly Tyler, of Mother Bethel, found a great-great-great-great-grandfather, the Rev. J. W. Devine of Pittsburgh, mentioned in an ad as a contact for former slaves seeking their families.

Last spring, Giesberg and Jerrido traveled to Yale University for a conference on digitizing African American history, where they met a faculty member who suggested using the ads as the basis for a theatrical project. Back at Villanova, Giesberg and Joyce set it in motion, with the hope that other schools will be inspired to follow suit.

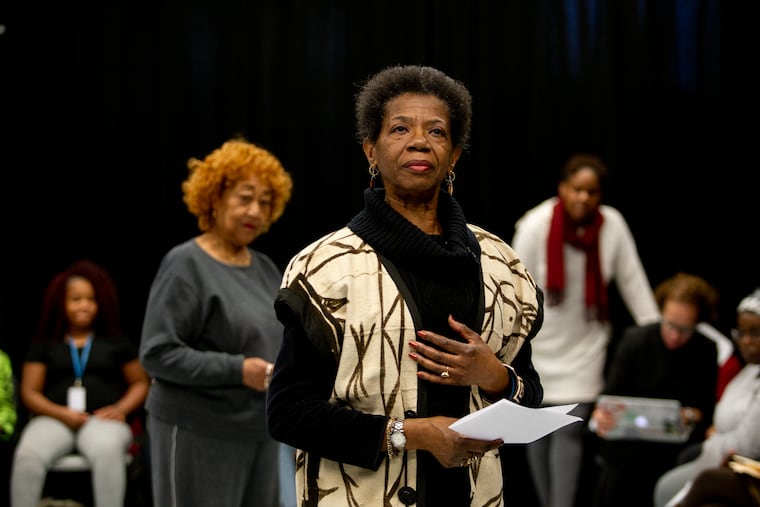

For their production, they put out a call for volunteer readers and wound up with a diverse cast ranging in age from 6 to 78 and including teachers, clergy, students, retirees, professors, and students from a performing arts school in Baltimore.

They had one rehearsal before Monday’s performance.

Jacquie Davis, 73, of West Philadelphia, a member of St. Matthew A.M.E. Church’s drama ministry, prepared for her role as Mrs. L.C. Carter of Chicago, who was looking for her son, Fred.

“He was last seen at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, Cal. You will do a great favor if you can tell of his whereabouts,” Davis said in a delivery that was both mournful and majestic.

Shirley Washington, 70, a retired program administrator from West Oak Lane, fought back tears as she read Ann Whaley’s letter.

“I could imagine myself just wanting to see what other people in my family looked like, to feel them, to touch them, to hug them,” Washington said.

Behind her, sixth graders from Tilden Middle School in Southwest Philadelphia waited their turn.

Alimah Crawford, 11, who passed up a birthday party to attend the rehearsal, walked to her mark and read a two-line ad placed in the Baltimore Sun by the brother of Kitty Collins, who was searching for his sister in 1865.

Afterward, Alimah said reading it made her feel “sad — and furious.”

Marla Mahoner, 45, a teacher from Delaware County, chose an ad placed in the Christian Recorder by Eliza Holmes, of Flatonia, Texas, who was looking for her son and her husband. “My son was sold in Richmond, Va., I don’t know where they carried him to,” the ad said.

The separation of parent and child resonated with her, Mahoner said. She never met her biological father and yearned for that missing connection, even though she was raised by a “wonderful" stepfather.

“No matter how old you are," she said, "it never stops that desire to want to be a part of something bigger than you.”

C.J. Miller, 40, said he felt the same emotional tug. A Villanova theater student, Miller says his daughter was adopted against his wishes and lives in Canada. For the production, he will read an 1879 ad placed in the Southwestern Christian Advocate, of New Orleans, by Henry Tibbs, who was searching for his mother. The last time he saw her, he was a little boy, Tibbs wrote, and she brought him “cake and candy.”

The words of former slaves need to be heard, said Tyler, the Mother Bethel pastor.

“Here we are, this far away from the Civil War, and we haven’t learned anything,” he said. There are “immigrant children at the border who’ve been taken away from their families and some of them may never see their parents again. I hope we will learn about our history, and that it will speak to our present. “