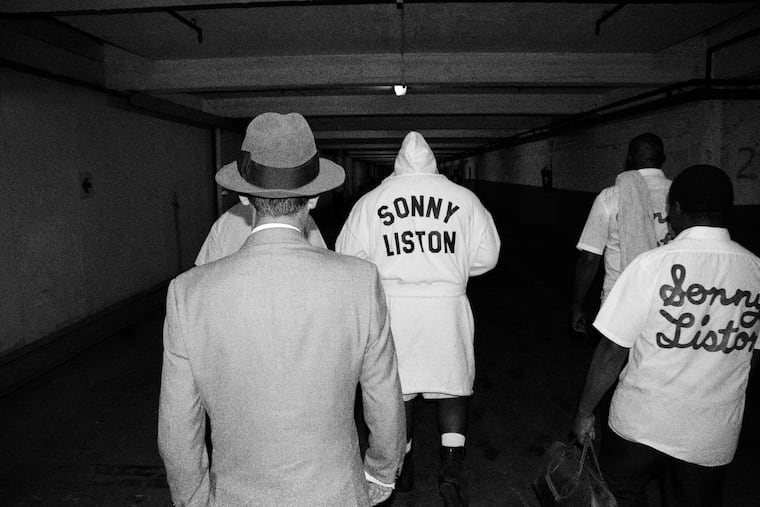

Documentary explores Sonny Liston’s harsh world and mysterious death, and how he found no love in Philly

Fans rejected Liston after he won the heavyweight title over Floyd Patterson in 1962. “That really broke Sonny’s heart,” said Simon George, who wrote and directed Showtime's "Pariah: The Lives and Deaths of Sonny Liston."

As soon as Sonny Liston departed the jet that carried him from Chicago to his adopted hometown of Philadelphia on Sept. 27, 1962, he knew he wouldn’t need the thank-you speech in his coat pocket.

The welcoming parade he expected after taking the heavyweight title from Floyd Patterson two nights earlier, a celebration he hoped would once and for all make America forget his sordid past, wasn’t going to happen. He heard no cheers, saw no crowd, felt no love.

That rejection – his Rosebud moment, according to Shaun Assael, the author of The Murder of Sonny Liston – set in motion a descent that saw the controversial boxer lose his title, lose whatever chance he had to transform a tragic existence, and, eight years later, lose his life.

“That really broke Sonny’s heart,” said Simon George, who wrote and directed Pariah: The Lives and Deaths of Sonny Liston, a Showtime documentary partially based on Assael’s book that debuts Friday night. “He gave up after that, unraveled. What was the point of being heavyweight champion if it didn’t get you more respect or more love and just made people hate you more?”

George grew up a boxing fan in England. He said Liston, so dark and menacing, was a figure who always intrigued him.

“We all know about the dark side, but he was an amazing fighter,” said George. “In watching him fight Cleveland Williams and others, it seems he may be one of the great heavyweights of all time. And I don’t think he’s remembered that way.”

Liston, who held the title for 17 months until he failed to come out for the seventh round in 1964 against Muhammad Ali, then Cassius Clay, was an enigma from beginning to end.

He was the 11th of 12 children born to a poor, abusive Arkansas sharecropper. His birth date was a mystery. So was his death, the documentary’s focus.

He was probably only 40 and living in Las Vegas in 1970 when his wife found him dead in their bedroom. The cause was listed as an accidental heroin overdose. But because of his organized-crime connections and drug use, the conspiracy theories started immediately and, as the documentary makes clear, never stopped.

In between, there were violent crimes, arrests, prisons, allegations of fixes, and a stellar career as a mob-controlled boxer who won 50 of 54 fights.

Liston was no ordinary pug. Powerful, relentless, and technically skilled, he’s still rated by many experts as one of the best heavyweights ever.

“He was a stalking kind of heavyweight with a big left hand,” said Larry Merchant, the longtime HBO boxing commentator who at the time was the Daily News’ sports editor. “He fought by the book. After the Patterson fights, there was a feeling that he was indestructible.”

But he was also a tough and sullen black man with a troubled past, one who couldn’t read or write. The sportswriters in that less-enlightened America assailed him, labeling him an ignorant thug. He fought back by refusing to talk to many of them.

“The press was vitriolic,” said George. “They tore him apart, made fun of him, always bringing up his mob ties, the fact that he was illiterate.

"At the time America wanted its black heroes to be like Floyd Patterson and Joe Louis, quiet and subservient. But in terms of the white press, Sonny Liston didn’t want to play those games and couldn’t see why he had to. In some ways, he wasn’t capable of playing those games. So he thought, 'If you’re going to treat me like this and hate me, then I’ll hate you back.’ ”

Liston learned to box in prison. He came to Philadelphia as a contender in the early 1960s after legal trouble drove him from St. Louis. Among his convictions there was one for assaulting a policeman.

“Philadelphia still had a reputation as a great fight town,” said Merchant. “There was a backlog of trainers and gyms.”

He trained with Willie Reddish and resided in Overbrook. But if his relationship with sportswriters was combative, it was worse with the city’s police.

In 1961, Liston was arrested for loitering outside a drug store, though he claimed he was merely talking with fans. Shortly afterward, he was accused of impersonating a police officer when he allegedly used a flashlight to wave over a woman driver in Fairmount Park. Those charges were dropped.

Following that 1962 snub at Philadelphia International Airport, Liston left for Denver, famously saying, 'I’d rather be a lamppost in Denver than the mayor of Philadelphia.’”

He destroyed Patterson again in their 1963 rematch, then lost his title to Ali.

Ali beat him again in their infamous Maine fight, when Liston fell to the canvas and was counted out in the first round. That gave rise to speculation that the fight, and perhaps even the first with Ali, was fixed, speculation Merchant dismissed.

“An awful lot of people have looked into those claims over the years,” Merchant said, “and nothing credible has ever been found.”

Liston won his last fight, a TKO over Chuck Wepner, the real-life “Rocky,” in 1970. Afterward, stories arose that he had double-crossed the mob by winning. Six months later, he was dead.

“By the time I was deep in this book, I had a pretty long cast of characters who I thought wanted to kill Sonny,” said Assael. “The easiest answer is sometimes the best, and while it was listed as an accidental overdose, I came to believe that while overdose was a possibility, accidental was not.”

The documentary, as the title suggests, dwells on Liston’s life and death, but it also serves as an indictment of the way America turned on a champion it refused to accept.

“He finally won a title and America didn’t want him,” George said. “It’s a parable about how America treats its heroes. It’s the story of a man reaching out to grab hold of the stars and getting burned.”