A Pa. cheerleader’s profane Snapchat rant lands before the Supreme Court

The justices expressed skepticism at the Schuylkill County teen's suspension for her foul-mouthed Snapchat post. But they struggled with the prospect of drawing broad lessons from her case.

>> Update: U.S. Supreme Court sides with a cussing Pa. cheerleader in student free-speech case

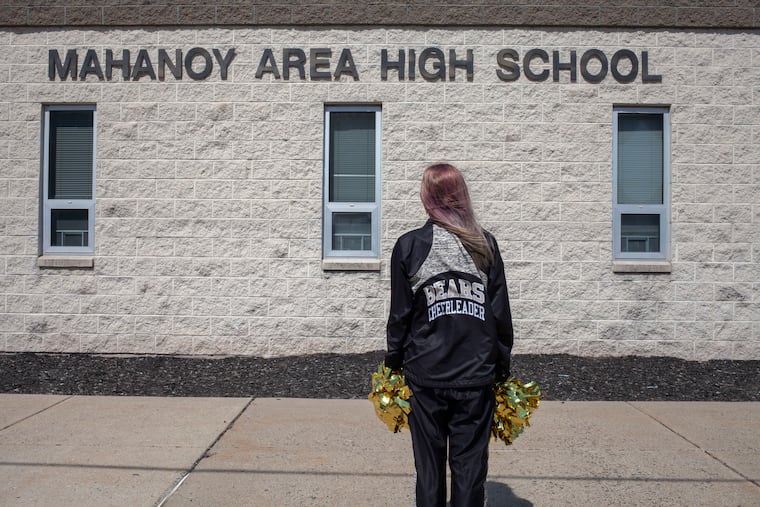

When Brandi Levy learned she’d been relegated to Mahanoy Area High School’s junior varsity cheerleading team in 2017, she did what most teens these days do — turned to social media to vent her frustration.

But her profane post on Snapchat — in which the then 14-year-old, middle finger extended, wrote “F— school, f— softball, f— cheer, f— everything” — didn’t just get her suspended from the squad for a year. It landed the Schuylkill County teen in the middle of what legal scholars have described as the most significant case involving the free speech rights of students to end up before the U.S. Supreme Court in 50 years.

On Wednesday, the high court’s nine justices spent two hours mired in an exercise all too familiar to many adults in the digital age — scrutinizing the social media musings of a teenager and debating just how seriously to take them.

At issue for the court was the extent to which schools should have discretion to discipline students for things they say off campus.

“She used swear words — unattractive swear words — off campus. But did that cause a material and substantial disruption?” asked Justice Stephen G. Breyer. “If using those words off campus were the issue, my goodness, every school in the country would be doing nothing but punishing.”

» READ MORE: Should a teen’s Snapchat rant have made it all the way to the Supreme Court? | Pro/Con

Like Breyer, most of the justices voiced skepticism that Levy’s posts were sufficiently disruptive to the school environment to warrant the suspension she received. Among them was Justice Brett Kavanaugh, a onetime coach for his daughters’ basketball teams, who called the response from Levy’s coaches a “bit of an overreaction.”

But when it came to the broader free speech issues raised by the case — and the prospect of defining a new legal standard for regulating off-campus speech in the digital age — the court struggled, appearing to worry that any hard-and-fast rules it might create could, on the one hand, prove overly restrictive or, on the other, leave schools powerless to deal with harassing and bullying online behavior.

“I’m frightened to death of writing a standard,” Breyer said at one point.

And yet, on that weekend in 2017 when she learned she hadn’t made the varsity team, lofty debates over the constitutional rights of students weren’t exactly at the forefront of Levy’s mind.

She posted the offending message on Snapchat in a fit of pique on a Saturday, outside of the cheerleading season, while hanging out with a friend at the Cocoa Hut, a convenience store in Mahanoy City, about 40 miles southwest of Wilkes-Barre.

It went out to her network of about 250 followers. Levy thought it would be deleted within 24 hours, like all posts on the social media app.

But one person took a screenshot and passed it to another, who passed it to another, and the post eventually found its way to one of her cheerleading coaches at Mahanoy Area High School.

The team based its decision to suspend Levy on team rules it said she agreed to follow when she signed up, including avoiding “foul language and inappropriate gestures” and a strict policy against “any negative information regarding cheerleading, cheerleaders or coaches placed on the internet.”

Levy’s parents, Larry and Betty Lou, challenged the constitutionality of those requirements in appeals to various athletic and school administrators and, eventually, a federal court with the backing of the American Civil Liberties Union.

“I was 14 years old and was at a point in my life when I was really frustrated with things that were happening around me,” Levy, now 18 and studying accounting at Bloomsburg University, said after the hearing. “This is how kids today express themselves and that they should be able to do that without worrying about being punished at school.”

The last time the Supreme Court took on such a wide-ranging student speech question was nearly a half-century ago in a case involving an Iowa school district’s ban on allowing students to wear black armbands to protest America’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

That case — Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District — led the justices to conclude that students and teachers do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” But they also empowered schools to punish disruptive speech, at least when it occurred on campus.

That standard has been used by thousands of school districts across the country in the years since.

In Levy’s case, a U.S. District judge questioned whether her Snapchat posts were truly disruptive and in 2017, ruled against the school district, ordering her back on the squad.

A three-judge panel of the Philadelphia-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit went further, breaking from other court rulings and definitively stating that the deference past case law gives schools to regulate disruptive speech on campus does not extend once the students leave at the end of the school day.

“New communicative technologies open new territories where regulators might seek to suppress the speech they consider inappropriate, uncouth, or provocative,” Circuit Judge Cheryl Ann Krause wrote for the panel. “And we cannot permit such efforts, no matter how well intentioned, without sacrificing precious freedoms that the First Amendment protects.”

The school district, education groups, anti-bullying organizations and even the Biden administration have since weighed in, saying the Third Circuit ruling goes too far in an age where instances of cyberbullying, harassment, and political threats to students occur both in and out of school and can affect the learning environment.

“Students shouldn’t be able to place their speech off limits just by stepping off campus,” Lisa Blatt, an attorney for the Mahanoy Area School District, argued before the Supreme Court on Wednesday.

But David Cole, the ACLU’s national director, pushed back, insisting there is a middle ground between regulating harmful speech and other kinds that simply run counter to how schools might hope their students would behave.

“Outside school they should have the same free speech rights that everyone else has,” he said. “If the school prevails here, young people will have nowhere they can speak freely without fear that a school official will punish them.”

The court is expected to issue a ruling in the case by the end of June.