The Parent Trip: Elizabeth Catanese of Fairmount

One healthy baby. That was Elizabeth’s mantra for months. And then -- "a two-for-one special."

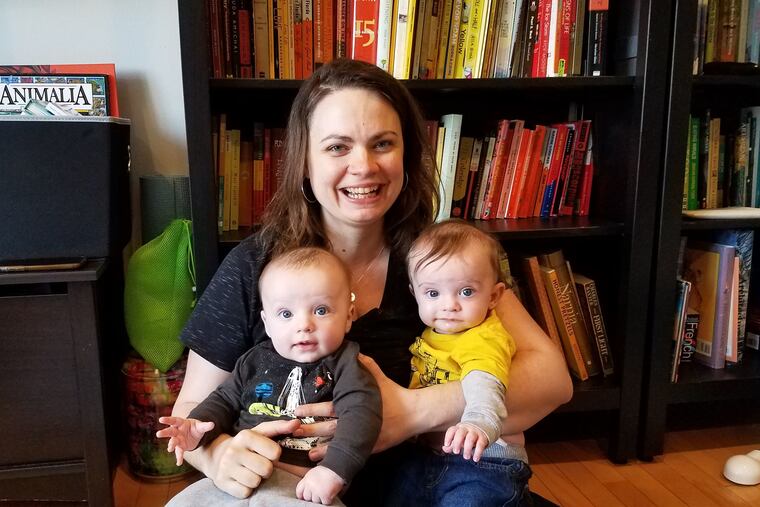

THE PARENT: Elizabeth Catanese, 34, of Fairmount

THE CHILDREN: Dylan Joseph and Escher Paul, born October 31, 2018

THEIR NAMES: “I wanted an artist-baby and a writer-baby,” Elizabeth says — one named for Dylan Thomas, the other for M.C. Escher. Their middle names are nods to family members.

One healthy baby. That was Elizabeth’s mantra for months — each time she paid $900 for a vial of sperm from the California Cryobank, each time she went to the fertility clinic for an intrauterine insemination, each time she injected herself with hormones to amp up her egg production.

And then there was the day — it was after the fifth attempt — when a nurse looked at the sonogram and said, “Oh, a two-for-one special!”

“I was laughing,” Elizabeth recalls. “For all my not wanting to have two, it was kind of funny that this had happened. I was going to figure it out and enjoy it.”

Elizabeth always knew she wanted to be a writer. But she wasn’t set on parenthood until her early 30s, when she watched her best friend go through the process of selecting a sperm donor and having a baby with her partner.

“At the time, I wasn’t in a relationship. I thought, “What would it look like if I had kids on my own?” That felt a little bit scary, but there wasn’t a huge reason to wait.”

She envisioned a chosen family with someone she knew as the donor, a man who would be a kind of uncle figure in the child’s life. But the two friends she asked said no, so she began poring over lists from the California Cryobank.

“It’s like online dating, in a way,” she laughs. “There were a bunch of donors who sounded a little bit full of themselves, like they were excited to be donors because they were so awesome. I wanted someone who seemed real and authentic.” With the help of friends, she chose a donor whose ethnic background matches her own Italian German heritage, a man who composes music and studied biology in college.

He’s also an “open-identity” donor, meaning he is willing to be in touch with any offspring, at their request, once they turn 18.

Some acquaintances cautioned Elizabeth about the burdens of single parenthood, tickling her own self-doubts: Would she be able to swing it financially? Would she be able to find good child care? Did she have enough experience with babies?

But her parents and close friends were supportive. “At one point, I was walking on the beach with my dad. My dishwasher had broken, and he said, ‘I want to buy you a new dishwasher.’ I said, ‘Thank you, but could you help me buy sperm instead?’”

The first insemination felt auspicious, even playful; a good friend came along, and afterward Elizabeth went to Target and bought a dress on impulse. But it turned out to be a chemical pregnancy, with no viable fetus. “It was so early, but it felt like a loss, for sure,” she says.

The second try didn’t work, either. Nor the third. Elizabeth tried boosting her luck with an Indian tradition that says tigers are a fertility symbol; to each insemination, she took a children’s book called Hold Your Temper, Tiger. She wore a necklace with a charm of a hippopotamus, a fertility animal in Egyptian culture.

And she thought about her grandfather, who had died several years before. The two often took walks by the ocean, and as Elizabeth lay on the doctor’s table, she would picture her grandfather watching over two children.

“He was holding on to them until they were ready to come. I would look up at the fluorescent lights and think about the ocean and about him and say, ‘Whenever you’re ready.’”

The fifth time, on Presidents’ Day, was the charm. But the pregnancy itself was difficult: constant vomiting, spacey behavior (she would turn off the light in her classroom at Community College of Philadelphia when she meant to turn on the projector) and, by the end, a belly so expansive that elevator doors sometimes refused to close unless she backed up and stood sideways.

In the meantime, Elizabeth converted her art studio to a room for the twins, and friends used a spreadsheet to sign up for meals and to provide company after the birth. Because the twins were breech at first, then constantly shifting position, she opted for a scheduled C-section. “By the end, it felt like two small dolphins that were swimming along under my skin,” she says.

She remembers feeling dizzy in the operating room at Pennsylvania Hospital after the first drips of anesthesia. She remembers someone saying, “Now it will feel like an elephant is standing on your chest.” She remembers her best friend holding her hand, her tears at the first glimpse of Dylan, and her laughter when just-born Escher peed on her.

She also recalls the emotional maelstrom of those early days. “I was not very mobile, and their swaddles kept coming undone. I thought: This is a metaphor for how I can’t be a good mother.” It got easier: Her parents helped, friends visited every day for the first six weeks, and her confidence gradually grew.

“I remember thinking, I’ll always have screaming babies and I’ll never sleep again and I’ll always be changing diapers. But it was joyful, really exciting, with so much adrenaline and awe at these little creatures who were suddenly here.”

There was also a new, unexpected village: eight other families who had used the same donor, in touch with one another through the cryobank registry. They created a Facebook chat, share photos each Friday, and talk about the ways, even as babies, that their children’s traits chime.

“I wanted the boys and myself to have a larger sense of family and connecting with other people,” Elizabeth says. And it’s turned out that single parenthood has its upside. “I get to make the decisions. When I make a mistake, I can’t blame anybody; there’s some power in that. This was probably one of the most empowered things I’ve allowed myself to do — to know what my needs were and do this thing I’ve so deeply wanted.”