Should third parties who want Trump defeated stay off the ballot in swing states such as Pa.?

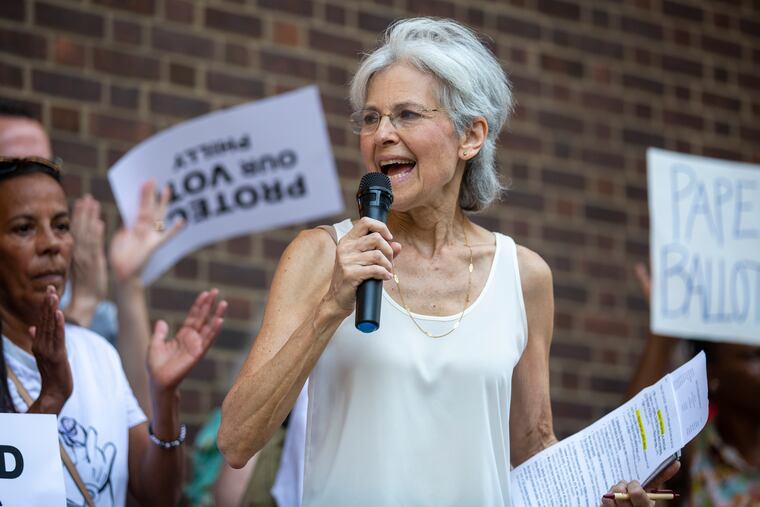

Hillary Clinton could have won Pa. if she’d gotten all of Jill Stein’s 49,960 votes in 2016, as well as her own. The likelihood of that having happened is slim, but it’s something Democrats point to as a factor in Trump’s win.

Jerome Segal isn’t your typical candidate for president, but as he’ll tell you, this isn’t a typical election.

Segal, founder and candidate of the newly created Bread and Roses Party, admits he has no vision of winning the presidency. A socialist, he’s also vowing not to campaign in such swing states as Pennsylvania. He’s denouncing those third-party candidates who are.

“It’s completely irresponsible for a progressive third party to compete in swing states,” Segal, a philosopher and activist who lives in Maryland, said in an interview. “It’s quite likely that it’ll be close and in a winner-take-all system, even if you do terribly in that state, that tiny percentage of votes can actually make a difference. Our view would be if the Green Party is on the ballot in Pennsylvania, don’t vote for them. Vote for Biden.”

Segal’s position is a provocative answer to one of the most common questions in presidential politics: Is a vote for a third-party candidate wasted?

President Donald Trump won Pennsylvania for several reasons in 2016, and the number of potential Democratic voters who instead cast their ballots for Green Party candidate Jill Stein over Hillary Clinton was one in a whole playbook of things that went right for Trump and wrong for Democrats.

Clinton could have won Pennsylvania if she’d gotten all of Stein’s 49,960 votes in 2016, as well as her own. The likelihood of that having happened is slim. Still, Democrats, headed toward an election — and their independent allies such as Segal — determined to beat Trump, are zeroing in on everything that allowed him to win Pennsylvania by 44,000 votes.

The Green Party disagrees with Segal’s framing. The party is already on the ballot in 20 states and petitioning to qualify in more, including Pennsylvania. Leaders have recently tried to pull in supporters of Sen. Bernie Sanders, who suspended his campaign and shares some similar policy ideas.

“The Green Party’s position is that Americans deserve as many choices as possible when we’re talking about the most powerful office in the country,” said Michael O’Neil, communications manager for the national party. “The language that particular candidates or parties spoil elections is oppressive language from the corporate two-party cartel that is designed to perpetuate their stranglehold on our two-party system.”

The problem, Greens have long argued, is with the electoral system. They want to eliminate the Electoral College and use ranked-choice voting, as many countries have adopted. (Segal agrees with them there.)

The Green Party opposes Trump but favors more sweeping changes than a traditional Democratic candidate such as Joe Biden is likely to achieve. It has pushed for a “Green New Deal” since 2012.

“Trump is a disaster, and I don’t think anyone in the Green Party would tell you otherwise,” said Hillary Kane, treasurer of both the Philadelphia and national Green Party. But she called “lesser evilism" a “garbage argument.”

“Increasingly globalized economy, housing inequality, social determinants of health — these things have existed for eons under successive Republican and Democratic administrations,” she said.

Kane challenges the notion that the Green Party “spoiled” the presidency for Democrats in 2016. She points to disenchanted Democrats in rural areas, a weak Clinton campaign strategy in key states, and voter suppression.

Backlash from Democrats against third parties has grown since Trump’s election, Kane said.

“Part of the danger of the two-party system is that when you have just a complete monster like Donald Trump in power, he and the Republicans make the Democrats look much better than they really are," O’Neil said.

The Green Party is in the process of choosing among three possible nominees: party cofounder Howie Hawkins; Dario Hunter, a member of the Board of Education in Youngstown, Ohio; and activist David Rolde.

There is an added logistical issue this spring of gathering the signatures most states require to file to run for office. Pennsylvania recently loosened the signature requirements for third-party candidates, but the Greens still need 5,000 to get on the ballot, which is hard to do with social-distancing requirements.

In a letter to the Pennsylvania secretary of state, the Pennsylvania Green Party, which has about 10,000 registered voters, asked that the signature requirement be waived for all independent candidates.

The Constitution Party and the Libertarian Party are also fielding candidates for the presidency.

In states such as Pennsylvania, to have a Green Party line on the ballot in nonpresidential years, the party must get at least 2% of the vote in the previous presidential election. That makes it harder to run local and state candidates under the Green Party banner, and also means the party must run a candidate for president in the state.

Daniel Franklin, a professor emeritus at Georgia State University, studied the effect of third parties in the 2016 election and looked back to the late 1850s. He wanted to find out whether third parties bring out new voters or pull votes away from the major parties. The study found that the larger the vote for a third-party candidate, the lower the turnout overall.

“What we suspect is happening is that third-party candidates serve habitual voters who are unhappy with both their choices," Franklin said.

The problem, he argues, is that in a two-party system, based on his research, voting for a third-party candidate effectively promotes your third choice over your second choice.

“Most of the voters who voted for Jill Stein at the end of the day would have preferred Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump,” he said.

For Segal, creating his own party was always about expanding the ideas surrounding how to govern, not winning. It’s easier to get attention for ideas by running for president than, say, writing a book (which he’s done).

The Bread and Roses Party is named after a textile workers strike in Lawrence, Mass., in 1912. Immigrant women demanded more pay but also shorter workweeks to be able to enjoy “the beauty in life,” which they considered the “roses” part of their platform.

Segal’s platform includes wanting every American to have more leisure time as well as two jobs — the one they do to make money — and a second in the creative or nonprofit sector that reflects their passions. He proposes a Beauty New Deal, emphasizing arts in education and beautifying the country.

Segal has never been a traditionalist. He was an instructor in the philosophy department at the University of Pennsylvania from 1968 to 1972, where he got in some trouble for unconventional grading techniques. He didn’t believe in them, so he first let students grade themselves. Then he tried giving everyone C’s, which upset students and administrators.

He just missed Trump, who graduated from Penn in 1968. He likes to think he would have had an impact if he’d had him as a student.

Helping Trump win a second term, however, is definitely not the kind of impact he’d like to have.

“It’s ironic," Segal said, “This is the one way in which tiny third parties can have a gigantic national impact.”