Trans prisoner was pepper-sprayed and says he was invasively searched at Philly’s female jail

Guards in Philadelphia’s only female jail use pepper spray more than twice as often as it’s used in male facilities.

It started with too many drinks and an argument over who should clean the house.

Zack got angry and landed a punch. His boyfriend grabbed a table leg and hit him in the chest. It ended with the cops at their University City apartment and Zack in handcuffs with one big worry.

As a transgender man, he was frightened about being put in a female jail and what the guards might do to him.

“I didn’t want to be outed,” he later said.

Zack, who is 34, transitioned in his mid-20s to identify as a man. Now in state prison, he agreed to share his story only if called by his first name.

In November 2016, he was locked up in Riverside Correctional Facility, the city’s only female jail, where, he said, he faced a series of dehumanizing abuses.

Records show officers gathered around at breakfast to laugh at Zack’s beard. One refused to refer to him as a man “until you grow a penis like me.” Another denied him shoes in retaliation for sticking to his identity, according to a lawsuit Zack filed in 2017 against the Philadelphia Department of Prisons. (He is identified in court papers by his initials.)

Zack also alleges he was sexually assaulted and subjected to a genital search, illegal under federal law and against the prison’s policy, according to the lawsuit.

And after he filed numerous internal complaints, Zack was aggressively pepper-sprayed by a correctional officer while others watched, even though he posed no apparent harm to nearby staff, video obtained by The Inquirer shows.

Moreover, his experience at Riverside isn’t rare. Jailers at the female facility use pepper spray at more than double the rate of its male facilities, an Inquirer review of internal prison data shows.

In 2018, Riverside, which averaged 466 prisoners per day, logged 124 instances in which jail guards used pepper spray on its detainees, according to internal prison reports.

At Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility, Philadelphia’s largest male jail, which had an average daily population of 2,140, guards used pepper spray 252 times.

“That is an objective sign of an abusive environment,” Claire Shubik-Richards, executive director of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, said of Riverside’s reliance on pepper spray. “This is a prison that knows about this turning a blind eye on an unhealthy, unsafe environment.”

Prison officials deny guards and medical staff abused Zack. They said they settled Zack’s lawsuit in 2019 because it “was in the best interests of the city,” department spokesperson Mallie Salerno said in a statement. After two months at Riverside, Zack was convicted of aggravated assault and sent to state prison.

Asked about Riverside’s high use of pepper spray, Salerno said:

“If the percentage of pepper spray incidents is higher at a given facility, it can indicate that there are more situations where inmates are refusing to be compliant.”

After Zack’s experience, Department of Prisons officials put in clearer policies on how to protect transgender people. But they have not ensured that staff are complying with the rules, records and interviews show.

‘I felt humiliated’

When Zack arrived at Riverside after his arrest, jailers did an intake search: Strip naked, rake your hair, rake your mouth, cough, and squat.

A few days later, staff ordered Zack to see Mariben Gonzales, a prison nurse working on contract.

She told Zack to get naked, lie on an examination table, and put his feet up in stirrups, he recalled, as prison Sgt. Allison Hardy stood nearby.

Gonzales testified in a sworn deposition that managers wanted her to confirm one thing: whether Zack was a man or a woman.

Zack did what he was told and put his feet up.

Under federal law, examining a transgender prisoner’s genitals in a visual or invasive manner, solely to confirm identity, is illegal.

The 2003 Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) specifically outlines how correctional officers should treat transgender prisoners. Officers, for example, should only search transgender persons with noninvasive pat searches over their clothes. Staff must also ask prisoners whether they want male or female officers to search them. Genital searches should only be done if part of broader medical examinations.

Despite the law, experts say penetrating, illegal searches of transgender prisoners happen far too often in prisons and jails nationwide, and are dehumanizing and unconstitutional.

In the exam room, Zack worried people in the halls could see what was happening.

“Wider,” Zack recalled Gonzales instructing.

Then she stuck two of her fingers into Zack’s vagina, he testified.

A few seconds later, he said, she looked at Hardy and said: “Female.”

“Female,” he said Hardy parroted.

“I felt humiliated,” Zack said.

Only later, Zack said, did he hear from a prison gynecologist that Riverside jailers and medical staff routinely conducted genital searches, court records indicate.

In testimony, Gonzales denied penetrating Zack with her fingers. She said she conducted a visual inspection of Zack’s vagina, to which she said he agreed. The company Gonzales works for, Corizon, also denies any wrongdoing on her part and declined to make her available for comment. Hardy denied being in the room during the vaginal search.

Mateo de la Torre, an advocate at the National Center for Transgender Equality, said invasive genital searches happen all the time. “You’re essentially stripping away every sense of dignity any human being should be afforded.”

Lasting pain

For Zack, the worst of it started at breakfast one morning in November 2016.

Correctional Officer Tahira Brew-Littlejohn mocked Zack for his beard and wanting to be called a man, according to the lawsuit.

“Trannies coming to jail,” Zack recalls Littlejohn saying.

He filed a complaint against her, and shortly afterward, Littlejohn moved to another unit.

After that, other officers continued the ridicule, he testified.

Zack continued his demand to be identified as male, but was met with hostility.

In testimony, Littlejohn denied verbally abusing Zack. The Prisons Department would not make her available for comment.

Zack, housed on the second floor of the jail, said the abuse took a toll.

“I wanted to jump off,” he said. “I was just so shocked in this environment.”

He continued to file grievances. In December 2016, a shift commander asked him to stop filing complaints and sign a document clearing the guards of wrongdoing. He refused.

He then was sentenced to 15 days in solitary confinement. Before sending him to solitary, guards rendered their own justice.

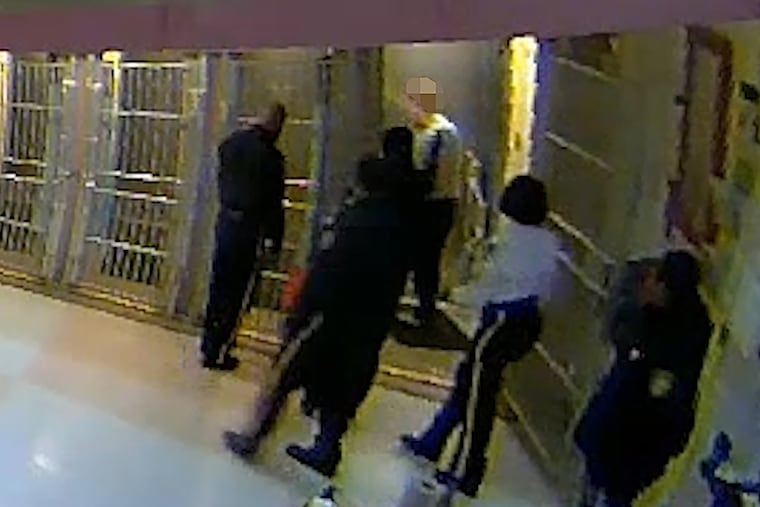

Video footage obtained by The Inquirer shows multiple officers gathered around Zack while he was in a shower. He refused to change into an orange jumpsuit worn by prisoners in solitary and “continued on rambling, saying this was unjust, this was unfair, he shouldn’t be locked in,” one of the officers, Monique Jones, testified.

Jones said Zack’s refusal was a hostile act, even though he was handcuffed. In the video, he is not being aggressive.

Jones, under orders of Sgt. Nakia Anderson, sprayed Zack in the face, footage and documents reveal. Over 30 seconds, Zack was pepper-sprayed in the face four times.

The Prisons Department would not make Jones or Anderson available for comment.

The Inquirer reviewed 25 minutes of footage of the incident. In it, not once does Zack physically resist, which raises the question of why guards responded with that degree of force.

“[There’s] a little bit of a sense that pepper spray is harmless,” said Alison Leal Parker, managing director of U.S. programs for Human Rights Watch. “It so clearly is not.”

Pepper spray can cause second-degree burns and lasting pain in the eyes, and trigger asthma or respiratory attacks for those with underlying health issues.

Facilities with high rates of pepper spray use, such as Riverside, are broken, experts say. That level of use can signal that a facility has a high rate of prisoners with mental health issues, Parker said. Usually, it means officers aren’t well-trained in the proper use of force or how to de-escalate tense situations with words.

The Prisons Department stands by its officers’ high use of pepper spray at Riverside.

“Pepper spray is the minimal amount of force to ensure compliance, and ensure the safety of all involved, including officers and inmates,” said Salerno in a statement.

‘I didn’t learn anything, really’

A key issue in dealing with transgender prisoners is training, experts say.

“It’s easy to have a good-looking policy, but the issue is: ‘Does that translate into practice?’” said Julie Abbate, national advocacy director at Just Detention International, who helped draft federal PREA standards. “Way too often, that answer is no.”

The city’s written policy on how to deal with transgender prisoners follows federal regulations, records show.

Even so, several prison staff said they were either never trained or poorly trained in how to handle the intake and care of transgender people, according to their depositions from Zack’s lawsuit against Riverside.

Gonzales said she’d never received this kind of training before she searched Zack’s genitals.

“There was a policy they sent after,” she said.

Jones, the correctional officer who pepper-sprayed Zack, said she’d never received transgender training prior to Zack’s arrival at Riverside. She also didn’t think that was the biggest issue.

“He is not the first transgender inmate we ever had, won’t be the last, but they weren’t as sensitive,” Jones testified.

Lawrence Wisinski, an officer who Zack said harassed him, also said he’d never received specific training on how to care for transgender prisoners until after Zack started complaining.

Asked what he retained from the training, Wisinski said: “I don’t remember because it was so quick. I didn’t learn anything, really. I am not going to lie. I still didn’t understand it, you know.”

One way to prove staff retain the policies prison management put into practice is to audit how well jailers comply with PREA regulations, said Abbate.

Yet, seven years after PREA standards were enacted, Philadelphia prison officials still haven’t conducted an audit, something the department’s own deputy warden in charge of PREA compliance, Patricia Powers, questioned as early as June 2018.

“‘We’re not ready’ is what I was told,” Powers testified.

What remains to be seen is if prison officials want to understand why pepper spray is used so often at Riverside, or learn why staff aren’t retaining the transgender training they’re offered, experts say.

Because if they don’t, advocates like Malik Neal, director of the Philadelphia Bail Fund, say the price is high: “Every year, we force thousands of Philadelphians into these dangerous places. You can call that many things, but justice isn’t one of them.”