Pennsylvania is critical in 2020. Here’s how Trump could win or lose it.

Pa. is a swing state with 20 electoral votes, tied for fifth most, and helped tip the 2016 election to President Donald Trump. How could he win again here in 2020? That equation is more complicated.

It’s simple: In any assessment of the 2020 presidential race, Pennsylvania is critical.

It’s a swing state with 20 electoral votes, tied for fifth most, and, with Michigan and Wisconsin, was one of three traditionally blue states that tipped the 2016 election to President Donald Trump.

The president’s campaign, the main Super PAC backing him, and top Democratic groups have all targeted the Keystone State as one of the most important on the map — a vital piece of the “Blue Wall” that Trump fractured, and that could prove decisive.

So, fresh off Trump’s official reelection announcement Tuesday, what does he need to do to win Pennsylvania again? That’s more complicated.

The 2016 result was so excruciatingly close in the state — decided by 44,000 votes out of more than six million cast, less than 1 percent — that tiny shifts in any part of the electorate could change the outcome next year.

There isn’t one key factor. There are many.

If Trump’s strength in Rust Belt, working-class counties and rural areas recedes even a small amount, he could lose.

If Democrats continue to surge in the suburbs, that could doom Trump.

If Democratic voters in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh move closer to the historic turnout levels seen under Barack Obama, that could flip the state back.

Or if Trump manages to pull in voters who didn’t support him in 2016, he could repeat his win.

Public polling, and even Trump’s internal polling, suggests the president starts with an uphill climb. Pennsylvania voters disapproved of Trump’s performance by 54 percent to 42, according to a Quinnipiac University poll in May, which also found the president trailing potential challengers such as Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders.

“No one is under any illusion that it’s going to be easy,” said David Urban, a Republican lobbyist who advised Trump on Pennsylvania in 2016. “I have personally spoken to the president and he is prepared to put in the time and effort that is required to campaign, work hard, contest, ask for every vote in Pennsylvania just like he did last time.”

Interviews with more than a dozen elected officials, activists, political operatives, and analysts, combined with a review of recent election results reveal several distinct battlegrounds within the state, each of which could help decide not just the outcome in Pennsylvania, but the entire campaign.

Here are some of the places that could shape the results:

Rural ‘Trump Country’

To win Pennsylvania, Trump needs to hold on to the largely white, postindustrial counties and rural areas he won here in 2016.

Nationally, Trump has accelerated a political realignment: historically Democratic, small urban communities hit by economic change and rural areas shifting toward the Republicans, and traditionally Republican suburbs moving toward Democrats.

Pennsylvania has seen both.

Consider Erie County, one of the most drastic examples. Barack Obama easily won the county in the state’s northwest corner in 2012. Four years later, it turned narrowly red, thanks to a 21,000-vote swing toward Trump — nearly half of the margin that decided the entire state.

The switch mirrored swings in other counties such as Luzerne, which saw a 32,000-vote shift toward the GOP compared with 2012, Lackawanna (a 23,000-vote shift), Northampton (11,000 votes), and Westmoreland (16,000), to name just a few.

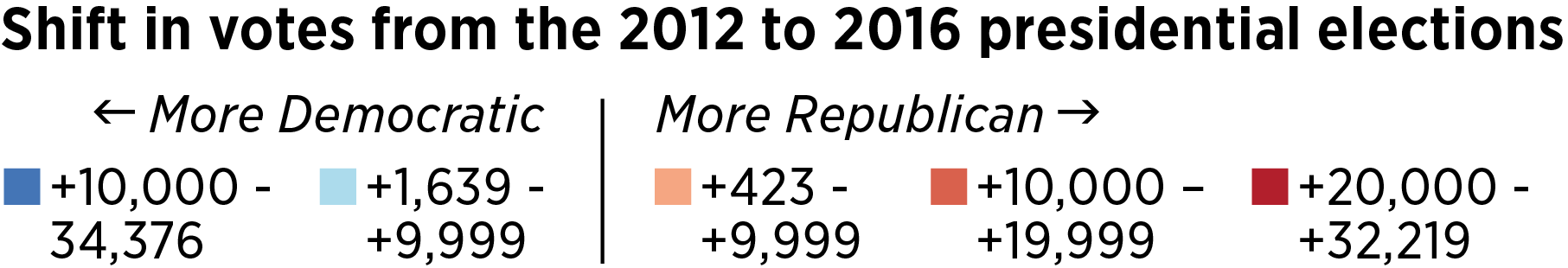

A Turn to Red in the Last Presidential Election

From the 2012 to the 2016 presidential elections, 63 of the state's 67 counties shifted more Republican in their vote margins.

Yet Democrats see a chance to regain ground in those postindustrial counties by at least cutting into Trump’s margins, if not winning them back outright. They point to the election results since 2016 as signs of hope.

In the 2018 midterms, for example, Sen. Bob Casey and Gov. Tom Wolf, both Democrats, won major victories in Erie, with margins close to those Obama enjoyed.

To some Democrats, their rebound signals that with the right message they can still compete in those areas. The hope for Democrats is that some people who supported Trump have had second thoughts, and that some of the results were simply a backlash against Hillary Clinton.

A Democratic congressional candidate from Erie, Ron DiNicola, ran TV ads featuring Trump voters who were supporting him.

“Looking at how Trump has performed in Pennsylvania statewide and in some of these swing areas, there is more evidence to conclude that it was more of an anti-Hillary vote than a pro-Trump vote,” said J.J. Balaban, a Democratic consultant who worked on DiNicola’s race. “He was seen, fairly or not, as the lesser of two evils. … Now, it turns out that Trump does not appear to be a wildly popular figure in Pennsylvania.”

Balaban notes that in four key counties that supported Trump -- Erie, Northampton, Beaver, and Luzerne -- Democrats running for down-ballot jobs like auditor, treasurer, or attorney general also scored victories in the same election — a sign, he argues, that voters there remain open to supporting Democrats.

As in Erie, Democrats in 2018 saw similar recoveries in other working-class areas as well, giving them hope they can improve enough to win the state back.

Polls suggest that the vast majority of Trump supporters have stuck with the president. So do anecdotal interviews with voters. But there are at least some Trump supporters who have expressed misgivings, and have pledged to oppose the president this time around. Trump’s relentless focus on firing up his base, meanwhile, has hardened opposition and done little to attract new supporters.

The president’s net approval rating in Pennsylvania has fallen by 17 percentage points since he took office, according to polling by Morning Consult.

“Who are the voters out there who didn’t vote for Trump that might vote for him this time? Because I think he needs a few of those, and they’re hard to find,” said Chris Borick, a pollster a Muhlenberg College. “That voter is elusive to me.”

Trump supporters argue that recent election results mean little for 2020, since the president, and his unique appeal, was not on the ballot.

“We’re going to have to turn out the folks that we turned out in 2016 in historic numbers,” Urban said. “All those little counties that people have forgotten about, … we’re going to turn those people out again.”

The Democratic suburb surge

Continued Democratic strength in the suburbs could be “apocalyptic” for Trump.

If Trump changed the political landscape in smaller urban counties in 2016, he did the same in suburban ones — but there it shifted against him; Democrats see evidence that they have expanded on those gains.

One Republican strategist worried that the suburban numbers for the GOP could go from “terrible” in 2016 to “apocalyptic” in 2020.

Consider Chester County, which narrowly supported Republican Mitt Romney in 2012, but gave Hillary Clinton a 26,000-vote edge in 2016. Two years later it elected a Democrat to Congress for the first time in recent memory, part of a wave that saw Democrats win almost every suburban congressional seat in the state.

More people in Chester County voted for Gov. Wolf in 2018 than for Clinton in 2016, even though presidential races usually draw more attention.

“There’s room [for Trump] to do a lot worse in the suburbs,” Balaban said.

In Western Pennsylvania, Democrat Conor Lamb won a House seat in a district that Trump had won by 20 percentage points, thanks to a strong showing in previously red suburbs. His special-election victory was backed up in 2018 by a win by State Sen. Pam Iovino, who captured another longtime GOP seat in suburban Pittsburgh.

Much of the swing has been driven by a new wave of activism led by women who can’t stand the president.

“The 2016 election was definitely a trigger, it was a wake-up call. What I realized and what a number of us realized at that moment was that if we don’t get involved in our democracy, we might lose it,” said Marie Norman, of Pittsburgh, who, in response, founded a volunteer network that now aids Democrats in local races.

A similar story has unfolded in Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery Counties, which accounted for nearly a quarter of the 2016 vote in Pennsylvania.

Republicans who hope to maintain a suburban foothold argue that Democrats have been pulled too far to the left by their party’s most strident voices.

“Centrist swing voters are not socialists,” said Josh Novotney, a Republican consultant based in Philadelphia. “I don’t think people like the massive policy dumps coming from the left.”

Turnout in the city

Will Democrats in the state’s two biggest cities, and the younger voters living there, turn out?

Before 2016, the conventional wisdom was that the suburbs effectively decided statewide races in Pennsylvania, serving as a virtual tiebreaker between liberal cities and conservative rural areas.

That’s partly why Democrats felt so confident as they saw Clinton rack up support in the suburbs.

But in Philadelphia, Clinton fell short of Obama’s 2012 tally and Trump won about 12,000 more votes than Romney had.

The result? Clinton won 84 percent of the Philadelphia vote, but her margin was 17,000 votes smaller than Obama’s in 2012. Democrats might be hard pressed to re-create the Philly enthusiasm that Obama stirred, but they could make up some ground if they get closer.

“If Democrats can really boost turnout in Philadelphia over 2016 levels, it’s an enormous advantage,” Borick said. “And it makes the math really hard for Trump. He has to squeeze even more voters out of those rural areas and try to flip some more voters, and that’s a really hard task.”