Philly ‘eliminated’ veteran homelessness in 2015. Why are there still vets on the street?

In years past, said Sister Mary Scullion, cofounder of Project HOME, as many as 20 percent of people living on the streets were veterans. Now, it’s 3 percent.

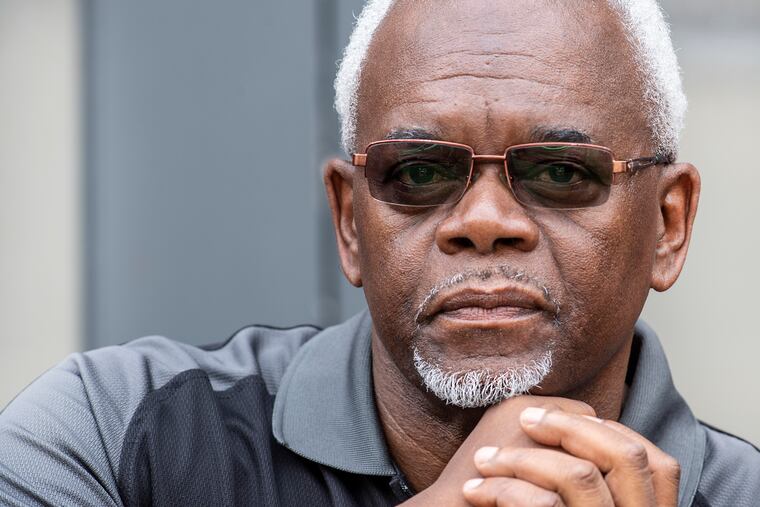

Marine Corps veteran Dwight Luckey became homeless last year after his wife of 34 years announced she wanted a separation. Money was tight and Luckey, a photographer and documentarian, had been jobless due to the pandemic. He ended up living in an empty building owned by a friend in Germantown with a caved-in roof and no hot water.

Possums clawed the walls at night and stray cats and dogs would meander through his bedroom in the mornings.

During the day, he’d walk the streets with his GoPro8 camera, documenting what he saw. His film, Lion’s Den, takes viewers through homeless encampments and explores how the folks he talked to got there. For many, it was a series of unfortunate events like Luckey’s.

Being homeless for three months brought him back to a time of darkness before he discovered faith. At just 17 he had enlisted in the Corps, and spent three years doing security for the Navy at a nuclear warhead station in Southern California. He had thought the military would give him a sense of purpose after a childhood racked, he says, with feelings of being lost and alone.

He felt hopeless living in that Germantown building and at one point even contemplated dying by suicide.

“You’re isolated. All you hear is your voice, or you use your voice, constantly,” said Luckey, 66. “I can relate now to when I see people on the streets talking to themselves.”

Homelessness in the Philadelphia veterans’ community was essentially declared solved by city and federal officials in 2015. But six years later, there are still vets on the street. While resources for them are plentiful, experts say social and mental roadblocks often prevent the community from asking for help — sometimes before it’s too late. Still, real progress has been made.

For Luckey, it was that sense of hopelessness that kept him from asking for help for a long time. He had noticed a sign on a bus that advertised services like housing for veterans. But he couldn’t bring himself to ask for help — at least not right away.

The military often produces veterans who are stoic and self-sufficient, noted David Oslin, chief of behavioral health at the Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center. Couple that with the stress that can come from service during conflict, and the perils for veterans are higher. People with post-traumatic stress disorder, a 2019 study in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine found, have an elevated risk of death from suicide, accidental injury, and viral hepatitis.

About 7% to 8% of Americans will experience PTSD at some point in their lives. For those who fought in Operations Iraqi Freedom or Enduring Freedom, that rate is anywhere from 11% to 20% in their lifetime. For the Gulf War vets, 12% have PTSD. And 30% of Vietnam veterans will have PTSD, according to the National Center for PTSD.

Veterans often have social, financial, or emotional barriers that make them hesitant to ask for mental health support, said Oslin, who is also a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

“Even if it’s not real,” he said, “the threat of that loss, of job loss, of employment, can be very stigmatizing.”

The VA Medical Center, located in West Philadelphia, touts its success reaching homeless vets. In 2020, the center found housing for 935 local veterans and assisted 2,367 walk-ins and appointments through its Community Resource and Referral Center.

There’s still a large group of veterans who have not opted into the services, and reaching those who are on the streets remains a challenge. VA nurses last year made contact with 437 unsheltered veterans and assessed their well-being and offered services at the VA.

On any given summer night in Philly, there are upward of 900 people living on the streets, and veterans make up a small portion of those, said Sister Mary Scullion, cofounder of Project HOME.

Back in 1996, 23% of homeless people had served in the military, according to Urban Institution, in conjunction with the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients. In 2010 it was 17%. Now, it’s 3%.

“People have experienced huge trauma,” said Scullion, whose organization often partners with the VA to coax veterans off the streets and into more stable situations.

Philly and federal officials announced in 2015 that they had reached “functional zero” for the homeless veteran population, meaning every veteran who wants housing has access to it.

» READ MORE: Homelessness 'effectively ended' for Phila. vets (from December 2015)

Not all who are in the system choose to transition to permanent housing. Although the number is relatively small, living on the streets has led to grave outcomes for some vets.

In 2017, Don Tyrone Donaldson died of hypothermia on the streets of Philadelphia. His friends and family were not aware he was homeless.

A month before his December death, Donaldson was featured as Frankford Gazette’s veteran of the month. He’d served in South Korea, Japan, and Vietnam from 1972 to 1976.

When friends and family reached out to him, he said he was fine, never letting on that he was homeless or that he needed help.

Others, like El Toro Datts, an Army vet from Philadelphia, spent two years living out of his car from 2017 to 2018. It wasn’t until the next year that he finally asked for help.

Datts enlisted with his brother in 1976, a year after the Vietnam War ended. He became an officer and served eight years before going out on disability. He earned three Purple Hearts.

After the Army, Datts, 64, had a career in engineering. His passion, though, was in long-haul trucking. It allowed him to be his own boss. He bought his own long-haul rig.

It was while out on a job in New Mexico in 2017 that he got hurt. He had already given up his apartment and had been living out of his truck. So when he didn’t qualify for disability, he sold his truck and started staying with a cousin, but that didn’t last long. Craving independence, he signed up for Uber, which at the time helped him afford a car, which he began sleeping in.

In 2014 Uber announced UberMILITARY, a program to help veterans become drivers, which included financing options to get them a car.

Datts, too, knew about the VA’s services but was reluctant to reach out. He’d often take his meals at the VA cafeteria. He called the VA one day in 2019 to complain about a Center City shelter he had tried out, which prompted a woman at the VA to begin calling Datts in an effort to find him help.

“Three times she called,” he recalled.

The woman’s persistence finally got to Datts, and he went into the VA in 2019 to get help. That November, the VA’s homelessness program gifted him a car.

Even though it was hard for Datts to ask for the assistance initially, he’s grateful.

On a bright summer afternoon, he could be seen in his one-bedroom apartment on 54th Street in West Philadelphia. A chess set sat next to the kitchen counter. An exercise bike stood by the window. His smile is bright now that he has a steady roof over his head.

Luckey has an equally easy smile these days.

After he finally called that number on the bus, he moved into a couple of different hotels through the VA’s housing program, and in March he settled into a permanent apartment in Strawberry Mansion.

Documenting how those without housing live in Philly has brought him a sense of purpose again, a sense of peace.

“What’s really keeping me juiced up is the opportunity to shine a light on the things that I’ve seen,” he said.