WHYY has not voluntarily recognized a new employee union. Now what?

Here's what usually happens when an employer doesn't voluntarily recognize a union.

An earlier version of this article on efforts to unionize workers at WHYY included details and speculations on possible outcomes, relying broadly on scenarios that can play out when companies face unionization efforts. However, it failed to get comments on several scenarios from WHYY management. This article has been updated to include that context.

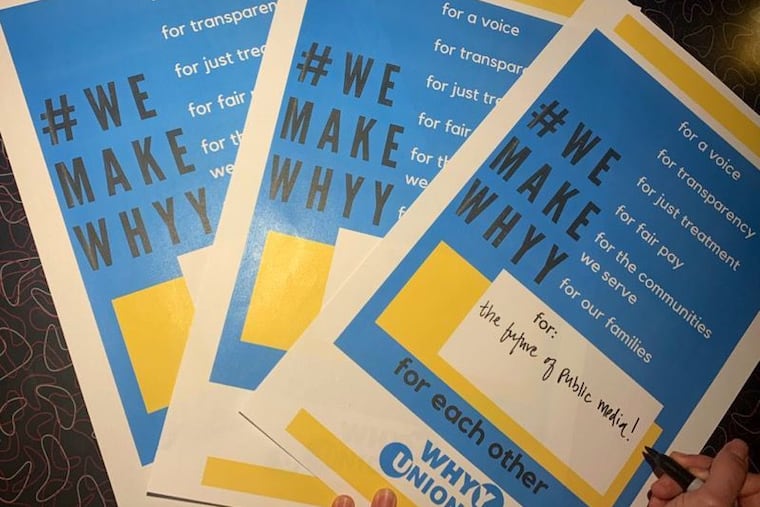

A group of workers at the public media station WHYY last week delivered a petition to management declaring their intent to unionize with SAG-AFTRA.

The workers, who said they were unionizing to turn the station into a place where they could build their careers “without sacrificing [their] well-being,” had support from more than 80% of the nearly 100-person proposed bargaining unit — well over the simple majority needed to win a formal union election — and asked management to voluntarily recognize the union, rather than requiring it to go through a National Labor Relations Board election.

WHYY has not voluntarily recognized the union.

Now what? Here’s an explanation of what could happen.

First, is it normal for an employer not to voluntarily recognize a union?

Yes, though it’s not unheard of for employers to voluntarily recognize. In the last two years, BuzzFeed, the New Yorker, and the Los Angeles public media station KCRW have all recognized their staff unions.

So what’s the formal election process unions must undergo if they’re not recognized?

It’s an NLRB election, where, in order to win, the union will need a simple majority: 50% + 1 person of all who voted. SAG-AFTRA, which represents public media stations including NPR, filed for an election Friday. The election generally takes place about four weeks after the filing. (It used to take almost twice that amount of time, but the Obama administration changed that.)

What happens in workplaces in the lead-up to those elections?

Generally, when workers announce their intent to unionize, it’s standard practice for employers to attempt to dissuade workers from voting for the union. As management-side lawyer Rick Grimaldi of Fisher Phillips put it, the employer uses the time before the NLRB election to “give employees the other side of the story.” Employers usually call this a period to educate their workers on the advantages and disadvantages of a union. Sometimes, though, employers agree to neutrality, promising not to carry out an anti-union campaign.

WHYY said in a statement, “WHYY is not anti-union nor have we made any attempts to dissuade workers from voting for the union."

Station spokesperson Art Ellis confirmed it has retained Duane Morris attorney James Redeker, who has been meeting with managers and senior management to brief them on “all the legal aspects of NLRB proceedings.” Redeker’s website says he has “engineered numerous successful counter-organizational campaigns for clients ... and conducted supervisory training throughout the country with respect to union avoidance.”

What would a ‘counter-organizational campaign’ look like?

It takes many forms. A common tactic is “captive audience meetings,” in which workers are told, during work hours, why they shouldn’t vote for the union. The talking points are pretty standard, said Valerie Braman, a Philadelphia-based labor educator and professor at Penn State. They’ll say: We’re a family. We have an open-door policy. Don’t bring in a third party. A staffer at WBUR, the public media station in Boston that voted to unionize this year, said colleagues joked those meetings were like playing bingo with all the antiunion talking points.

WHYY confirmed it plans to hold meetings during working hours in the coming weeks.

“These meetings will not try to dissuade employees from voting for or against forming the union but are designed to educate employees about what forming a union would mean now and in the future,” WHYY said in a statement.

Can management say anything in these meetings?

Not exactly. Management is barred by labor law from threatening, interrogating, and making promises to workers in the proposed unit. (It can, however, threaten managers, who are not covered by the National Labor Relations Act.) Still, there are gray areas, Braman said: Employers can’t say, “If you vote for the union, your salary will get cut." But they could say something like “With a union, you might end up with the same salary, or you might end up with something less.”

In a random sample of 1,000 NLRB elections, Cornell University’s director of labor education research, Kate Bronfenbrenner, found as part of her 2009 report that in 57% of elections, employers threatened to shut down the workplace, and in 47% of elections, employers threatened to cut wages and benefits.

Last year, Penn State suggested to its international graduate students that they could get deported if they unionized and went on strike. Students ultimately voted against the union.

It’s also illegal to fire someone for organizing or being pro-union. In Philly last year, parking companies fired six workers after they expressed their support for unionizing with 32BJ SEIU. Five of them got reinstated after several months.

Who enforces these laws?

The NLRB. If a union thinks an employer has broken the law, it can file an “unfair labor practice,” but these cases take time, and the penalties range from reinstating a fired employee to paying back wages to posting a notice in the workplace saying that it broke the law. The Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board recently took a more aggressive stance and ruled that the graduate students at the University of Pittsburgh should get a new election because the school illegally swayed the vote.

Braman, who used to organize for the AFT Pennsylvania teachers’ union, said that some employers make the cost-benefit analysis that it’s worth it to break the law to send a message to workers. Grimaldi says he tells his clients the most important thing in a union campaign is to not break the law.

Is it worth it for employers to fight a union if there’s overwhelming support for one?

Generally, employers want to keep unions out at all costs. Once unions are in, it’s hard to get them out. That said, Braman said, in WHYY’s case, more than 80% is an overwhelming majority. WBUR’s union had the same amount of support when it first declared its intent to unionize and won the election, 73-3.

WHYY said it’s important for the station to educate its workers.

“WHYY does not know what was said to employees or the other circumstances that may have led some to express support for the union,” it said. “WHYY feels it is our duty to help our employees make an educated decision on this issue. We respect our employees’ right to consider this course of action.”