Suspect in murder of off-duty cop walks free after former top prosecutors committed ‘egregious’ misconduct, officials say

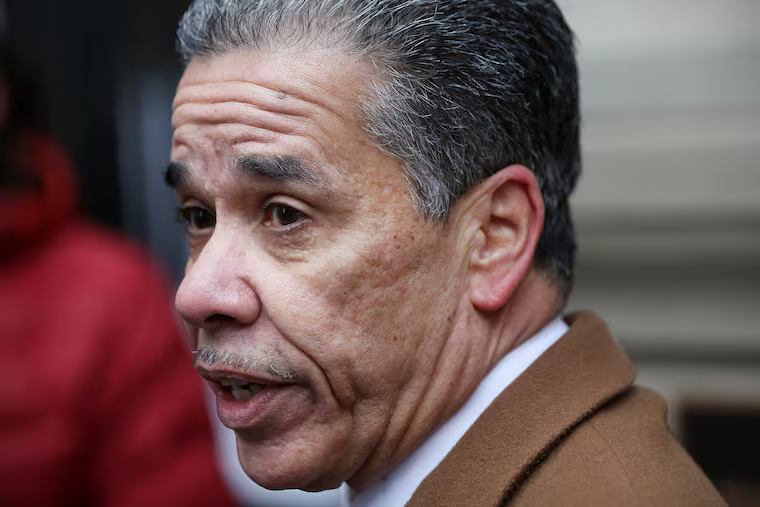

Prosecutors accused former DA Lynne Abraham and ex-homicide prosecutor Carlos Vega of withholding key evidence. Vega denied that and said the DA's Office had "slandered" him.

A Philadelphia man who was convicted in 2009 of fatally shooting an off-duty city police officer was released from prison Thursday after prosecutors said they recently discovered that a key trial witness had sent letters to top staffers — including then-District Attorney Lynne M. Abraham — saying detectives had coerced her into providing a false statement in the case.

The letters, prosecutors now say, were sent before the woman went on to testify against William Johnson at two trials, the second of which resulted in his conviction for third-degree murder in the shooting death of Officer Terence V. Flomo. But the letters — which could have been crucial in challenging the woman’s credibility — were illegally withheld from Johnson’s trial lawyers, prosecutors said, and remained undisclosed for years as Johnson appealed his case in both state and federal courts.

Assistant District Attorney Katherine Ernst, speaking in court Thursday, called the situation an “egregious” violation of Johnson’s rights by both Abraham and the trial prosecutor to whom one of the letters was addressed, former Assistant District Attorney Carlos Vega.

Ernst said she spoke to both Vega and Abraham about the letters in recent weeks as the office evaluated whether to re-try Johnson. Ernst said Vega “never squarely answered” what he did with the letters, and said Abraham told her if Vega hadn’t disclosed them, it was likely because he thought the woman’s claims were “bulls—.” Ernst called that a “startling admission” from a former district attorney because prosecutors are bound by law to disclose relevant evidence even if it’s helpful to the defendant.

Abraham, in an email Thursday, said Ernst provided the court with “false information” because: “I never mentioned Carlos Vega at all.” Abraham also questioned why she was never called as a witness in the case as the appeals wound their way through the courts.

Vega said in an interview that the DA’s Office had misrepresented its interactions with him and “slandered” him in court. He said that after Ernst had reached out to discuss the case, he asked her whether he could review the files in order to refresh his memory of a prosecution he handled more than a decade ago.

Vega said Ernst told him he could do so, but only if he would agree to be videotaped and review the materials while other prosecutors were present — terms Vega called unprecedented and “outrageous.”

Vega has a longstanding and bitter rivalry with District Attorney Larry Krasner, which was on full display two years ago as Vega ran for DA in an attempt to unseat Krasner. Vega also lost a lawsuit last fall in which he’d accused Krasner of firing him in 2018 because of his age. And Krasner, on the campaign trail and in court, repeatedly called Vega a liar and frequently pointed out his role retrying Anthony Wright, who was acquitted of rape and murder in 2016 after DNA evidence undercut the original theory of the case.

Vega said he didn’t know whether that history factored into the way the office behaved toward him in this case. But in an email to Ernst, which he shared with The Inquirer, Vega said he believed the conditions were being suggested for another reason: because he is Hispanic.

“The request on your behalf reeks of an ulterior motive that singles me out based on my ethnic background,” Vega wrote. “The only difference between me and the other former prosecutors who have been allowed to review the files without conditions is our race.”

Vega said he was “outraged” by what he viewed as attempts to bar him from reviewing the files in order to provide accurate answers, and that his “protocol has always been to give” exculpatory material to defense lawyers.

Prosecutors, in court documents, said the suggested terms were simply an attempt to maintain the integrity of their files.

The unusually pointed back-and-forth came as Common Pleas Court Judge Lillian Ransom agreed to dismiss all charges against Johnson. The decision moved his relatives to tears in the courtroom, but they declined to comment afterward. Johnson, who was incarcerated at a prison near State College, was released Thursday afternoon, his lawyers said.

Nilam Sanghvi, legal director for the Pennsylvania Innocence Project, which represented Johnson, said she believed the nature of the undisclosed evidence made the case “particularly egregious,” even in a city where so-called Brady violations have led to dozens of other convictions being overturned in recent years.

Flomo’s relatives were not in court Thursday, Ernst said. Attempts to reach them afterward were not immediately successful.

The crime for which Johnson was convicted was the fatal shooting of Flomo, an undercover narcotics officer and married father of four who was shot while off duty on Aug. 26, 2005. The prosecution’s theory at trial was that Flomo drove to 20th Street and Cecil B. Moore Avenue about 2 a.m. and spoke to two drug-addicted women who were out on the street as sex workers, and that two men — Johnson and Mumin Slaughter — then fired into his car.

The women’s statements were key pieces of evidence against Johnson and Slaughter. At the initial trial, in 2007, a jury voted to convict Slaughter of charges including third-degree murder, while failing to reach a unanimous verdict for Johnson.

Prosecutors re-tried Johnson two years later, this time armed with a new statement from Slaughter that implicated Johnson. But Slaughter disavowed the statement and refused to testify. A judge allowed prosecutors to present the statement to the jury anyway, and the panel voted to convict Johnson of crimes including third-degree murder. He was later sentenced to at least 30 years behind bars.

On the day he was sentenced, Johnson told the judge: “I do not feel I was given a proper trial.”

Johnson’s attorneys appealed, arguing in part that the introduction of Slaughter’s statement — without his testimony from the stand — violated Johnson’s right to cross-examine a key witness. Appellate courts generally agreed, prosecutors said, but judges consistently ruled that the statement’s admission was harmless because of the women who had identified him as a shooter.

But in 2020, one of the women, Brenda Bowens, recanted while speaking to Johnson’s attorneys. And they and prosecutors found letters in Johnson’s case file that they said Bowens had sent to Abraham and Vega in 2006 — before either trial — in which she said her statement was coerced by detectives.

“I’m a person with a conscience and also a human being,” she wrote to Abraham, according to a copy filed in court.

Prosecutors now say those letters were illegally withheld from Johnson’s trial attorneys. And after both sides filed new documents based on them, a federal judge agreed to vacate Johnson’s conviction earlier this spring.

Ernst, of the DA’s Office, said prosecutors no longer have confidence in the evidence against Johnson, although they do not fully back his claim of innocence. She also said prosecutors are likely barred from re-trying him anyway because of the manner in which they believe his rights were violated.

While Johnson was released from prison, it was not clear how, or if, the revelations might impact the case of Slaughter, his co-defendant. Slaughter remains in prison for his third-degree murder conviction, court records show.