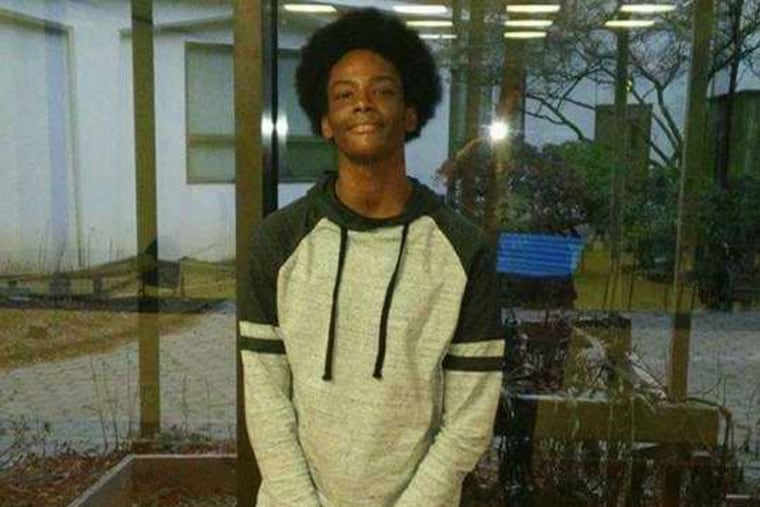

Two years after Wordsworth teen’s death, more details released but no charges

A report released this week said that David Hess, 17, was pinned to the ground in a headlock before he lost consciousness, and then given chest compressions — at one point by a tired employee who used his foot.

The 17-year-old boy who died in a struggle with staffers at Wordsworth Academy in 2016 was pinned to the ground in a headlock before he lost consciousness, and then given chest compressions — at one point by a tired employee who used a foot — while an ambulance took more than 30 minutes to arrive, according to new details in a report about the death.

David Hess, who had been sent to the residential facility for troubled young people due to his behavioral needs, also had apparently been inappropriately restrained by staff members in the weeks leading up to his death and had an “antagonistic” relationship with at least one staffer, according to the fatality review report, prepared by the Philadelphia Department of Human Services’ Act 33 team. The panel of child welfare experts, doctors, and police review fatal and near-fatal incidents involving children.

Names of all staff members are redacted from the report, and two years later, no one has been charged in his death, which the Medical Examiner’s Office had deemed a homicide.

Ben Waxman, a spokesperson for the District Attorney’s Office, said in an email Thursday that prosecutors “are in the process of reviewing the investigation to make the appropriate charging decisions."

Steven Marino, a lawyer for Hess' family, said he did not believe charges would be filed.

“For whatever reason, they decided not to pursue a criminal prosecution,” Marino said. “The case is over two years old, so what does that say? It’s up to them, but I doubt there will be a criminal prosecution.”

Marino settled with Wordsworth, which filed for bankruptcy in June 2017, for an undisclosed amount on behalf of Hess' family.

Hess' death prompted the state to order the closure of Wordsworth, the city’s only residential treatment facility for troubled young people. The Inquirer and Daily News subsequently reported that the West Philadelphia facility had a hidden history of abuse, with dozens of sex crimes and allegations of abuse having been reported at the facility for years before Hess was killed.

Hess died the night of Oct. 13, 2016, after multiple staff members entered his room after he was suspected of stealing another child’s iPod. He became upset after the incident and, according to the newly released report, was punched in the ribs and put in a headlock by a male employee who had his forearm on Hess’ neck. The man removed his arm as Hess started gasping for air. The medical examiner has said Hess died from lack of oxygen.

The report includes interviews with nine youths who lived on the same floor as Hess as well as counselors involved in the incident, nurses, and emergency responders. One of the youths said an employee “did not like David" and alleged that during a restraint two weeks prior, the employee “took advantage of the situation and punched David in the chest.” Another youth reported that a month earlier an employee had hit Hess in the face while Hess was restrained.

The night of Hess’ death, staff members said, he left a meeting without permission, angering a male employee, who “went off” for several minutes because he thought Hess had acted disrespectfully. The interviewee also questioned why an employee not assigned to Hess' unit that night had gotten involved in the situation and entered Hess' room.

The report noted, “There appeared to be an antagonistic relationship between David” and one of the staffers.

Because the names are redacted, it is unclear if the statements refer to multiple staff members or one person. It has been reported that three counselors were in and out of Hess’ room when he died. Three Wordsworth staffers were placed on administrative leave following Hess' death.

The report also revealed how ill-prepared staffers were to handle an emergency situation. They did not properly administer CPR, using chest compressions but not mouth-to-mouth, the report says. At one point an employee “grew physically tired, so he began doing chest compressions with his foot."

Once Hess had become unconscious, a call to the nursing staff went unanswered, and no one called 911 until a nurse responded several minutes later and couldn’t find the teen’s pulse. An ambulance didn’t arrive for 30 to 40 minutes, according to the report, and was delayed getting to Hess “because Wordsworth security did not know the floor where the emergency was occurring.”

Staff lied to both the responding nurse and emergency medics, according to the report, saying Hess “hit his head on the floor, took a deep breath, and then coded.”

In its review of the incident, the Act 33 team noted failures in basic safety planning, training and supervision. Neither the on-call physician nor the Wordsworth medical director was contacted the night of Hess' death. The decision to restrain Hess was made “by an employee who had little training and experience,” the team wrote.

The report follows one released by two advocacy groups last week, which said the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services — which issues licenses to the state’s residential facilities — has failed the state’s most vulnerable children by allowing its system of residential facilities for troubled or disadvantaged youths to become plagued by physical and sexual abuse, poor supervision, or other problems.

The state did not respond to requests for comment Thursday.

Cynthia Figueroa, the head of Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services, which is separate from the state agency and did not oversee Wordsworth, said the case remains “deeply distressing."

“Every child’s life is valued,” Figueroa said. "And those entrusted with the care of David Hess should be held accountable.”