Wyeths and beyond at Brandywine: Two shows —one museum moving forward

Jamie Wyeth's paintings of his late wife Phyllis have a surprisingly tender side. American paintings from the Scaife bequest let you decide whether or not the home team won.

“Presenting Wyeth and American Art” — that’s the tagline the Brandywine Museum of Art uses on its brochures, and it offers a clue about the way the institution feels it needs to evolve.

Despite the Brandywine’s close relationship to the Wyeth family and the landscape they often depicted, a museum needs to move forward. There seem to be no more Wyeths on the horizon (though the work of the female Wyeths clearly deserves attention, as the Michener Museum’s extraordinary show on Henriette Wyeth last year demonstrated).

Thus, the Brandywine Museum has increasingly focused on American art and illustration beyond the Wyeths and on art that deals with nature and the landscape. It is currently showing two exhibitions that speak to different sides of its mission.

One, “Phyllis Mills Wyeth: A Celebration,” through May 5, is a hardcore Wyeth exhibition. It consists of works by Jamie Wyeth spanning more than 50 years, all of which depict his wife, who died in January. The other, “American Beauty: Highlights from the Richard M. Scaife Bequest,” through May 27, speaks of a more institutional future for the Brandywine, focused less on a family’s charisma and more on a representative collection of American art.

The Phyllis Mills Wyeth show is by far the smaller of the two — with 38 paintings and drawings. It was pulled together seemingly in an instant, mostly because Jamie Wyeth and a few others took paintings off their walls and brought them to the museum. Probably only the Brandywine could pull together something this good this fast because, for the Wyeths, the museum is almost family.

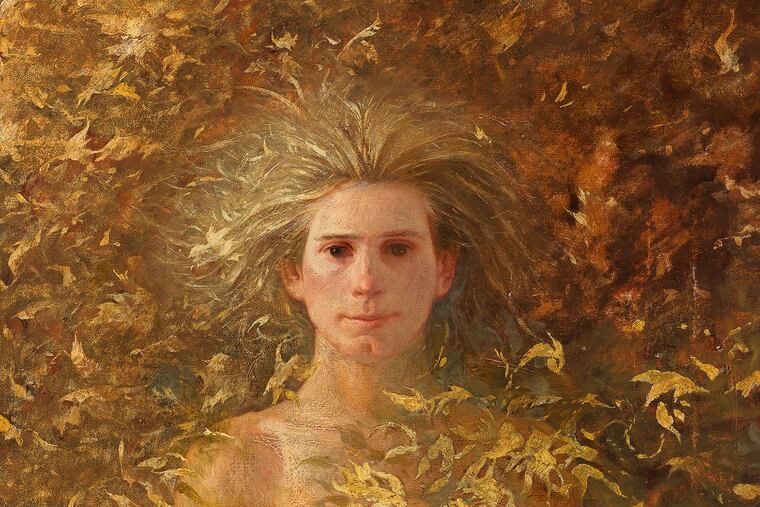

Jamie Wyeth has always appeared the most well-adjusted and happiest of the Wyeths, not always an advantage when the family brand is picturesque alienation. His decision, after a period in Andy Warhol’s circle during the 1960s, to marry a du Pont heiress four years his senior and permanently disabled from an automobile accident, always had a whiff of the commercial about it. But what we see here, from hippie-inflected wood-nymphish portraits from a half century ago, through decades of living on a farm filled with animals, is a wonderful record of long-term emotional intimacy, respect, and love.

Wyeth has turned again and again to his wife as an inspiration, and she is the subject of some of his most memorable paintings. Even those who feel, as I sometimes do, that Jamie Wyeth’s whimsical prettiness can be cloying will forgive him for his 2012 depiction of Phyllis beneath trees, balanced on her cane, sticking out her tongue to catch the pollen falling from the trees.

Like his father Andrew Wyeth’s most famous work, Christina’s World, it is work about longing and reaching. But it is a more optimistic work. She can reach and catch the pollen. Happiness is within reach and all around.

Mellon family pictures

Richard Mellon Scaife, an heir to the Pittsburgh industrial and banking family who died in 2014 at 82, was well-known, but not for his art.

Unlike his Mellon cousins and ancestors who founded and gave major collections to the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the Yale Center for British Art, Scaife seems not really to have concentrated on his collections. Instead, he spent millions underwriting numerous investigations designed to drive President Bill Clinton out of the presidency. By creating new kinds of partisan media and organizations built on the idea that Clinton’s administration and his party were illegitimate, he was a key shaper of the political world in which we now live.

Still, the man was a billionaire. He had four houses — two in Pennsylvania, one on Nantucket, and one in California. And each of those houses had walls to fill. Thus, it was inevitable that Scaife would have an art collection.

It included some big names in American art from the mid-1800s into the 20th century. Among them are Albert Bierstadt, William Merritt Chase, George Inness, Martin Johnson Heade, and John Frederick Kensett. For the most part, these are not signature works — the Bierstadts, for example, are missing the CinemaScope grandeur one expects of the artist. They were chosen for display in domestic interiors, and many are pleasant, decorative, and even interesting, but rarely memorable.

In his will, in what Brandywine Museum director Thomas Padon called “a watershed moment” in the museum’s history, Scaife bequeathed the museum half of his collection. He specified that the Brandywine and the Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg, Pa., near his principal residence, would divide his collection equally. Each museum took turns, in a process that was a lot like a sports draft.

There was an understanding that each museum would pick things that would fill holes in its collection, or that were of interest in their respective regions, though both museum directors were clearly looking to acquire the best works left. Indeed, much of the fun of the show is second-guessing their picks and trying to figure out who got a better selection.

For example, Chase’s 1899 Interior, Oak Manor, which shows a dark, heavy, opulent interior, is quite a haunting painting. Its Pittsburgh setting and feeling probably make it a better fit for Western Pennsylvania, and that is where it went.

The Brandywine, which had first pick, used it to get Heade’s New Jersey Salt Marsh (ca. 1875-85), a painting that is more or less all sky, a twilight moment in which the clouds appear to be illuminated from beneath. Heade was from Bucks County, and these flatlands are still visible in places on the way to the Shore, so it belonged here.

Thus, it was a perfectly respectable first pick. It is on display next to Westmoreland’s first pick, Moonrise, Alexandria Bay (1891) by Inness, another end-of-the-day scene, with deep greens, blue, and pink. It is freer than Heade, less a document of a natural phenomenon than an outward representation of an emotional or spiritual state. The two works show roughly contemporary artists faced with comparable scenes and responding to them in very different ways.

As a rooter for the home team, I regret that the Brandywine cannot keep both on display permanently. I guess only a billionaire can do that.

ON EXHIBIT

Phyllis Mills Wyeth, through May 5, and American Beauty: Highlights from the Richard M. Scaife Bequest, through May 27.

Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, open every day 9:30 a.m.-5 p.m., 610-388-2700, brandywine.org/museum.