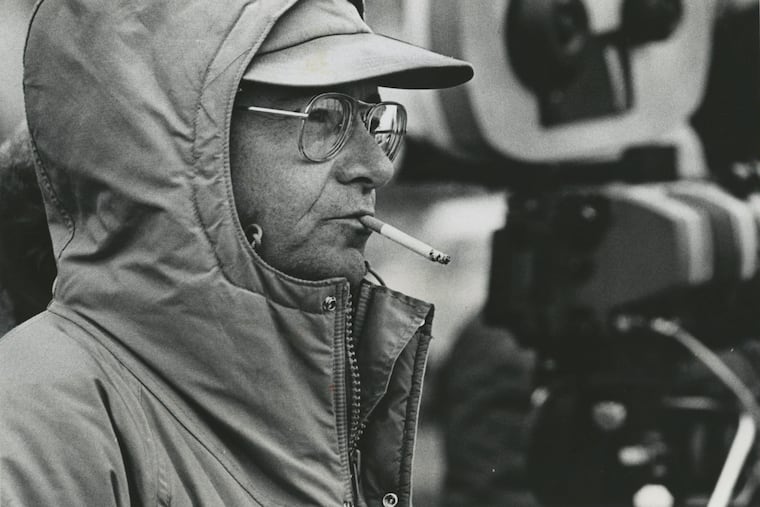

Buck Henry, ‘Graduate’ screenwriter who co-created ‘Get Smart,’ dies at 89

Buck Henry created the satirical spy sitcom "Get Smart" with Mel Brooks, was a frequent early host of "Saturday Night Live," and turned "plastics" into a countercultural catchword with his screenplay for "The Graduate."

Buck Henry, a comedian who created the satirical spy sitcom "Get Smart" with Mel Brooks, was a frequent early host of "Saturday Night Live" and turned "plastics" into a countercultural catchword with his Oscar-nominated screenplay for "The Graduate," died Jan. 8 at a hospital in Los Angeles. He was 89.

The cause was a heart attack, said his wife, Irene Ramp.

A restless entertainer, Henry dabbled in improvisational comedy as well as theater, television and film. He received an Academy Award nomination for co-directing the 1978 afterlife comedy "Heaven Can Wait" with star Warren Beatty; wrote scripts for the sex farce "Candy" (1968), based on the novel by Terry Southern, and the Barbra Streisand screwball comedies "The Owl and the Pussycat" (1970) and "What's Up, Doc?" (1972); and appeared as a droll supporting actor in nearly every film he helped create, including a turn as an anxiety-inducing hotel clerk in "The Graduate" (1967).

"I never wanted to stay at anything very long," he told the New York Times in 2002, while performing in a Broadway revival of the Paul Osborn comedy "Morning's at Seven." "I'm moderately lazy, and I'm interested in much too large a list of things other than my career."

Henry maintained a close association with "Saturday Night Live," where he hosted 10 episodes in the show's first five seasons and helped establish its transgressive brand of humor.

He played Lord Douchebag, an 18th-century English nobleman who observed that "Parliament has always had its share of Douchebags, and it always will," and he portrayed a film actor who abuses a "stunt baby," throwing the crying infant - a prop - against a grandfather clock before flinging it through a glass window.

The skit, and a follow-up that featured a howling "stunt puppy," triggered a torrent of angry letters from viewers. But the segment seemed almost timid compared with Henry's depiction of Uncle Roy, a Polaroid-wielding babysitter who encourages his young wards (Laraine Newman and Gilda Radner) to lift their dresses and hunt for "buried treasure" in his pants.

Created by writers Anne Beatts and Rosie Shuster, the recurring segment first aired in 1978. At Henry's urging, the writers crafted a closing joke in which Uncle Roy slyly gazed into the camera and insisted that he was not "one in a million," but rather that "there's more of me than you might suspect," a reference to what Henry took to be the widespread nature of pedophilia.

"In other words," Henry said in "Live from New York," a 2002 oral history of SNL, "I talked myself into the fact that we were performing - or that I was performing - a public service."

Off camera, Henry cultivated a reputation as a dry-witted comedian-intellectual, claiming to read 200 periodicals each year.

He was "the funniest and most serious guy I'd ever met - simultaneously," said the late director Mike Nichols, a childhood friend with whom Henry collaborated on an adaptation of Joseph Heller's "Catch-22" (1970) and, somewhat less successfully, "The Day of the Dolphin" (1973), a thriller about a plot to assassinate the president using English-speaking dolphins.

"The Graduate," based on Charles Webb's 1963 novella, remained their most enduring project. The film made a star of Dustin Hoffman, who played Benjamin Braddock, a college graduate who has an affair with his parents' friend Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft). Mixing wry comedy, sexual drama and a soundtrack by Simon & Garfunkel, the film captured the alienation and rebelliousness of the era and was later ranked No. 7 on the American Film Institute's list of the 100 best American movies.

Much to his frustration, Henry shared his Oscar nomination for "The Graduate"with Calder Willingham, who had worked on previous attempts to adapt the novel and sued to receive partial credit for the screenplay.

The book provided much of the film's dialogue - including the oft-quoted line "Mrs. Robinson, you are trying to seduce me. Aren't you?" - but it was Henry who devised the "plastics" exchange, in which a business associate of Benjamin's parents offers career advice to the lost young man.

"I just want to say one word to you, just one word," the businessman declares. "Plastics. . . . There's a great future in plastics. Think about it. Will you think about it?"

The suggestion neatly encapsulated what some viewers saw as the artificiality and materialism of older generations.

"I was trying to find a word that summed up a kind of stultifying, silly, conversation-closing effort of one generation to talk to another. Plastics was the obvious one," Henry told the Orlando Sentinel in 1992. "I was embarrassed some years later. I got to know some people in the plastics business, and they were really nice."

Henry Zuckerman was born in New York on Dec. 9, 1930. (Long known as Buck, after a grandfather, he later legally changed his name, his wife said.) An only child, he invented a pair of imaginary siblings, telling friends they lived in New Jersey because he assumed nobody would ever go there to visit. His father was a prominent stockbroker, and his mother was silent-film actress Ruth Taylor, who played the flighty Lorelei Lee in the 1928 gold-digging comedy "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes." (Marilyn Monroe portrayed Lee in the 1953 screen musical version.)

Henry graduated from Dartmouth College in 1952 and performed with an Army theater group before beginning a long, Benjamin Braddock-like period of what Henry described as "vigorous, total unemployment, characterized by a great deal of sleep."

That lifestyle changed around 1960, when he began performing with the Premise, a Greenwich Village improv group, and developed an offstage alter ego as G. Clifford Prout, the prudish president of a spoof organization called the Society for Indecency to Naked Animals.

Founded by prankster Alan Abel, the group took comic aim at "uptight, silly morality chasers," as Henry put it. He declared that "a nude horse is a rude horse," attempted to place boxer shorts on a baby elephant and was covered by credulous news programs including Walter Cronkite's "CBS Evening News."

The exposure helped him land writing jobs for TV variety programs and appearances on "That Was the Week That Was," a satirical news show. With Ted Flicker, founder of the Premise, he also wrote his first movie, "The Troublemaker" (1964), a comedy about a farmer who arrives in New York to start a coffee shop and realizes he must bribe officials to cut through red tape.

The film bombed - "the world wasn't really waiting for the final definitive attack on the cabaret-licensing system in New York City," Henry quipped - but that same year he was paired by a production company with Brooks in an effort to duplicate the success of the spy series "The Man from U.N.C.L.E."

The result was "Get Smart," a sitcom featuring Don Adams as bumbling secret agent Maxwell Smart. The series debuted in 1965 and resulted in an Emmy Award for writing for Henry, who served as the story editor for two of its five seasons. (Henry's relationship with the better-known Brooks frayed over the issue of equal billing, with credits listing the show as "By Mel Brooks with Buck Henry.")

Henry's first marriage ended in divorce, and in 2008 he married Irene Ramp, his sole immediate survivor.

His later film credits included the critically disappointing 1980 political farce "First Family," which was written and directed by Henry and featured Bob Newhart as an ineffectual U.S. president, and the screenplay for "To Die For" (1995), a mockumentary about a murderously ambitious newscaster played by Nicole Kidman.

Henry also continued acting, appearing as Tina Fey's father in the NBC sitcom "30 Rock" and as himself in Robert Altman's 1992 movie "The Player," a Hollywood satire that began with Henry pitching a producer on a sequel to "The Graduate."

The movie, he said, would be set 25 years after the original and would feature a stroke-impaired Mrs. Robinson living with her daughter, Elaine, who had by then married Braddock; Julia Roberts would play their adult daughter.

“I thought . . . it would stop people from ever calling me about a sequel,” he told the film magazine Cineaste in 2001. “Instead, of course, the opposite happened. There was a big screening . . . and my scene got a big laugh. In the lobby afterwards, a studio guy came over and said, ‘Good joke, good joke. Now let’s talk serious about it.’ So dumb ideas never die.”