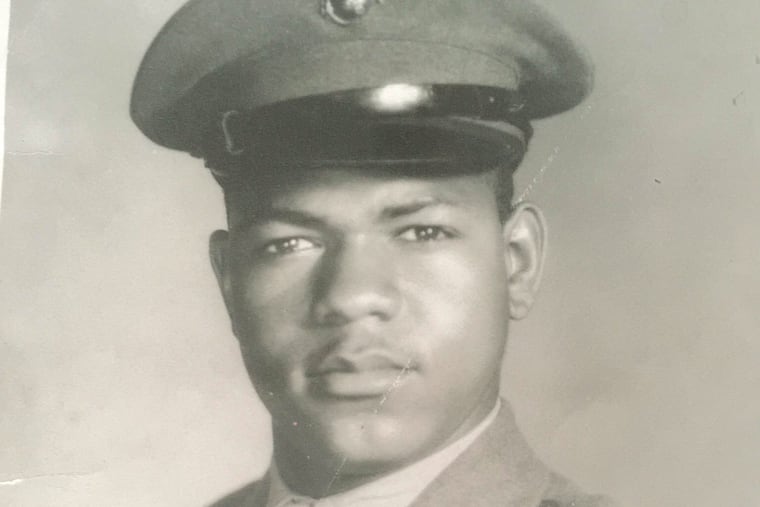

Earl Guydon, 95, made history during World War II as Montford Point Marine

Mr. Guydon was one of the first African Americans to integrate the Marines in World War II. Seventy years later, they were honored by Congress.

Earl Guydon, 95, of Philadelphia, a former construction worker who was among the first African Americans to integrate the U.S. Marine Corps during World War II and who was honored 70 years later with the Congressional Gold Medal, died Monday, May 20, at home.

Mr. Guydon was a member of the Montford Point Marines, whose name derived from the training facility they were sent to in North Carolina. The black recruits lived on swampy land in Quonset huts, while their white counterparts lodged in relative luxury at nearby Camp Lejeune.

From 1942 until 1949, almost 21,000 recruits trained at Montford Point. Some, like Mr. Guydon, saw combat in World War II. He took part in the occupation of Japan and was honorably discharged with the rank of corporal at the war’s end.

In 2012, he and other Montford Point Marines were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the country’s highest civilian honor awarded by Congress, during a ceremony in Washington.

“We are grateful that he lived long enough to witness the well-deserved recognition of America’s first black Marines,” said his daughter Deborah Linville. “Dad was extremely modest and humble, but that recognition meant a lot to a man who grew up in Arkansas in the 1930s.”

Mr. Guydon was the fourth of 11 children born to John and Willie Guydon in Clarendon, Ark. John, a widower, brought 10 children from a previous marriage. All 21 were raised as one family.

His mother taught at the local “colored school,” Linville said. It was her influence and educational discipline that instilled in him a love of learning.

When Mr. Guydon was 16, his father died, leaving him as breadwinner. He quit school and hired out to local farmers. That experience formed his work ethic, Linville said.

In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, banning discrimination in defense practices. The order paved the way for integration of the armed forces, but at the start of World War II, the Marines still hadn’t complied.

In 1942, that changed when Mr. Guydon and others like him registered for the draft and were assigned to the Marines. They immediately faced racial discrimination. They had only white officers. They weren’t welcome at Camp Lejeune unless with a white officer. Their quarters were primitive.

The Quonset hut “looked like a barrel turned on its side and there were 62 guys in one hut and one stove in the middle,” Mr. Guydon told the Chestnut Hill Local in 2012. “If you weren’t close to the stove, you had a rough night. The mosquitoes were bad, too. No windows, either.”

After the war, Mr. Guydon returned to Clarendon. Then he set out to visit siblings nationwide. He got as far as Philadelphia when, while attending Vine Memorial Baptist Church, he met Shirley Forte. They married and settled in Mount Airy. She died in 2017.

Faith was a cornerstone of Mr. Guydon’s life. He read the Bible daily. He served as a deacon, first at Vine Memorial, then at Bright Hope Baptist Church.

He never sought the limelight. When Congress announced that it would present the gold medal to the Montford Point Marines at a June 2012 ceremony, he didn’t want to go. “He acquiesced only because Shirley insisted,” Linville said.

“Earl Guydon was a quiet pioneer who simply wanted to serve his country. He was elated and reluctant to receive the Congressional Gold Medal, but I’m so glad he did, so his family will now have that legacy forever,” said Joseph H. Geeter III, spokesperson for the Montford Point Marines Association.

Mr. Guydon spent 40 years as a construction laborer before retiring at age 65.

“He liked nothing more than sitting on the front porch, with Rusty, his Doberman, by his side. The two would greet the schoolchildren as they walked past the house in the morning and afternoon,” Linville said.

In addition to his daughter Deborah, he is survived by sons Lee and Jonathan; daughters Sandra, Sharon Allen, and Barbara Ash; three grandchildren; a brother and sister; and nieces and nephews.

A memorial service will be at 6 p.m. Tuesday, June 4, at Bright Hope Baptist Church, 1601 N. 12th St., Philadelphia. Burial is private.