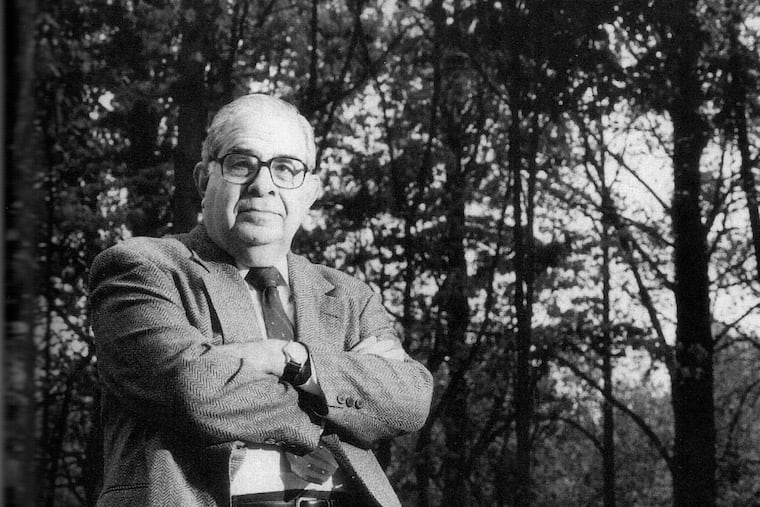

Gerald Shur, founder of the Federal Witness Protection Program, dies at 86

Mr. Shur's passion for rooting out organized crime grew from his father's angst over the mob's influence on New York's garment industry. "His anger was the fuel that fed my fire," Mr. Shur said.

Gerald Shur, 86, of Warminster, the founder of the U.S. Federal Witness Protection Program, died Tuesday, Aug. 25, of complications from lung cancer at his home.

During 34 years as a lawyer with the U.S. Justice Department, Mr. Shur relocated and provided new identities for more than 6,000 witnesses and 14,000 of their dependents, according to Pete Earley, a friend and former journalist with whom he wrote a book.

“No witnesses got protection without his personal attention,” Earley said in a tribute. “He wrote nearly all the program’s rules, shaped it based on his own personal philosophical views, and guided it with an iron hand. He helped create false backgrounds, arranged secret weddings, oversaw funerals.”

The witness program was one of three tools that helped take down Mafia kingpins in the second half of the 20th century. The others were federal wiretaps and the Racketeer-Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act, Earley said.

The tools allowed the government to break La Cosa Nostra’s vow of silence. Informants no longer feared being killed by the mob for testifying; instead, they vanished into another identity.

Mr. Shur was involved in the case against every major Mafia figure from 1961, when he joined the Justice Department, until he retired in 1995, according to Earley.

“We do everything we can to help witnesses, including finding them jobs in their new locations, but we have strict rules,” Mr. Shur said in a 2008 Inquirer article. “When you assume a new identity, you may never return to your past life. You basically forfeit your chance to attend your mother’s funeral.”

Some couldn’t handle the isolation and resurfaced, but no protected witness who followed the rules was killed, Mr. Shur said.

Born in the Bronx, New York City, Mr. Shur graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School in 1951. He graduated from the University of Texas at Austin with a bachelor’s degree in business administration in 1955 and a law degree in 1957.

His passion for defeating organized crime had its roots in his father’s experience as a representative of dressmakers in negotiations with labor in New York’s Garment District. He saw the influence organized crime had on the garment industry.

“My father was a member of the United Popular Dress Manufacturers Association, and he would complain about organized crime in the industry,” Mr. Shur told The Inquirer. “He couldn’t engage in the normal collective-bargaining process because the racketeers would interfere. His anger was the fuel that fed my fire.”

In 1961, Mr. Shur was practicing law in Corpus Christi, Texas, when he read that Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy was planning to open an office to combat organized crime. Mr. Shur was granted an interview and flew to Washington the next day.

“I was hired without even having a resumé,” he recalled.

He joined the Justice Department’s Organized Crime and Racketeering Section as area coordinator for all organized-crime investigations conducted by the FBI and other federal agencies in New York City.

Within a few years, he became the liaison with Joseph Valachi, a convicted drug trafficker who gave the public its first glimpse of La Cosa Nostra’s operations, rituals, and members during Senate committee hearings in 1963.

One of Mr. Shur’s last informants was Sammy “the Bull” Gravano, who had admitted to 19 mob killings. He was given a new identity and relocated after testifying in 1992 against New York Mafia boss John Gotti.

In addition to directing the witness protection program, Mr. Shur also oversaw programs involving covert criminal investigative techniques used by federal agencies.

In 1983, he led a mission to ensure the safety of the judge, jurors, and witnesses in the trial of the El Salvador national guardsmen accused of raping and killing four American Catholic missionaries, three of them nuns.

Among his awards were the John Marshall Award and the Mary C. Lawton Award for career achievement, both given by the attorney general.

After retiring, he collaborated with Earley on the 2002 book WITSEC — Inside the Federal Witness Protection Program. The book chronicled the founding and history of the program.

Mr. Shur is survived by his wife of 68 years, Miriam Heifetz Shur; daughter Ilene Meckley Clark; son Ronald; six grandchildren; and seven great-grandchildren.

Plans for a life celebration were pending.