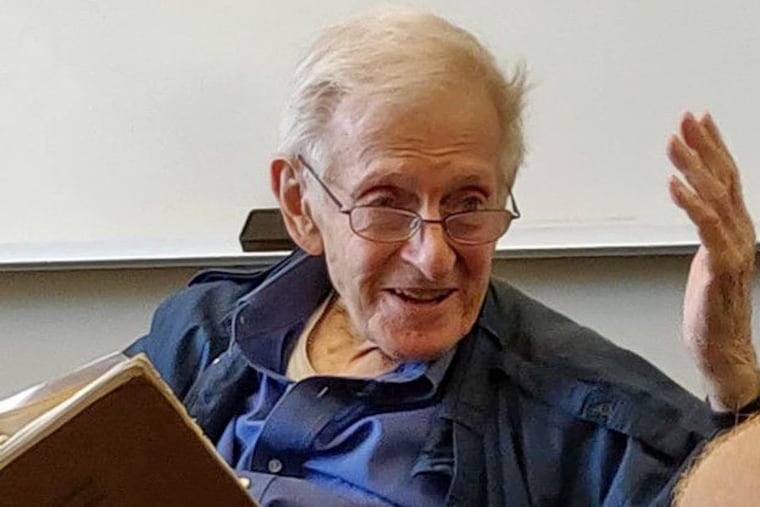

Joseph Margolis, philosopher, Temple professor, dies at 97

“My dad looked at what it means to be human, including how to live a life that is meaningful and deeply moral, even in the absence of faith,” his son said. Mr. Margolis died June 8.

Joseph Zalman Margolis, 97, renowned philosopher and author, died Tuesday, June 8, of heart failure in his Philadelphia home.

At the time of his death, Mr. Margolis was writing a paper that would have anchored the final project of his life — gathering the many strands of his 70-year career into a trilogy of books of his philosophy.

A few weeks before, he had received advance copies of his latest book, The Critical Margolis, a selection of his papers and book chapters from the last 25 years. In addition to his more than 30 books, he penned countless papers and chapters in anthologies. Some have been translated in Chinese, Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Polish, and Russian. Margolis was fluent in French, German, Italian, and Spanish as well as his native English.

The philosopher and his twin brother Israel were born in Newark, N.J., to Harry and Bluma Margolis. Israel Margolis arrived on May 15, 1924, followed minutes later by Joseph Margolis just after midnight on May 16.

Their father, a dentist, was a leader in the local Jewish community. Joseph Margolis respected his father greatly, but went his own way.

“He did not follow his father in faith, instead becoming an atheist at an early age. But living a righteous life, without judging others, was important to him,” said his son, Mike.

It would figure significantly in his work.

“My dad looked at what it means to be human, including how to live a life that is meaningful and deeply moral, even in the absence of faith,” his son said.

Mr. Margolis had his first brush with fame at age 4, when a local newspaper reported that he rescued his brother from a burning building.

During World War II, the Margolis twins went off to fight. Joseph Margolis volunteered to be a paratrooper. He was injured in the Battle of the Bulge and later awarded the Purple Heart, his son said. While he was in a foxhole, he learned his father had died in New Jersey and his twin had been killed in France, the son said.

After the war, Mr. Margolis got a bachelor’s in romance languages from Drew University. But when a professor suggested philosophy might be a better field for the student’s analytical mind, he obtained master’s and doctorate degrees in philosophy from Columbia University.

Over the course of his career, Mr. Margolis and his work greatly touched the lives of others.

“Many of his students have gone on to become major philosophers themselves,” his son said.

Mr. Margolis taught at Long Island University, the University of South Carolina, the University of California at Berkeley, the University of Cincinnati, and the University of Western Ontario.

But Temple University was his academic home. He started teaching at Temple in 1967 and held the Laura H. Carnell Chair of Philosophy from 1991 through 2021.

“Joe was an outstanding philosopher, known and admired wherever people practice academic philosophy,” said Espen Hammer, chairman of Temple’s philosophy department. “He was also a wonderful colleague and a great teacher. He is very highly missed.”

Mr. Margolis was so committed to teaching that he continued to work until halfway through the spring semester, said Asia Friedman, of Wynnewood, one of his grandchildren and a sociology professor with the University of Delaware. He even worked through the pandemic, instructing students on Zoom, she said.

”Joe is just the warmest, most humble person and so committed to the life of the mind,” she said. “He never wanted to retire. He felt if he ever stopped, that would be the end. He wasn’t ready for that.”

Austin Rooney, a professor of philosophy at Rutgers University-Camden, studied with Mr. Margolis while working on his doctorate at Temple and worked closely with him.

Rooney said Mr. Margolis was his own person, an original, from his preference for typewriters over computers to his dedication to and love of teaching to his open-ended, seminar teaching style that left room for many views.

“He was very supportive of students of all stripes, whatever project they were interested in,” Rooney said.

“He also was very careful not to force his own views on things,” he added. “He had a light hand. He wanted people to flourish on their own terms.”

Mr. Margolis also formed friendships throughout the world, his son said, many of them with people he met during his frequent trips abroad to speak at international philosophy conferences or lecture at universities in over 25 different countries around the world.

“Joe lived his life with courage and integrity and died with dignity,” his son said. “His family, friends, students and colleagues will miss him very much.”

In addition to his son and granddaughter, Mr. Margolis is survived by another son, Paul Margolis; a daughter, Naki Margolis; daughter Jennifer Friedman; eight grandchildren; three great-grandchildren; and other relatives. His first wife, Cynthia Baimas; second wife, Clorinda Goltra; and daughter Lovegrove Hunter died earlier.

A memorial service for Mr. Margolis will be held from 12 to 3 p.m. Sunday, July 25, at Banca, 600 Spring Garden St., Philadelphia, Pa. 19123.

Staff writer Susan Snyder contributed to this article