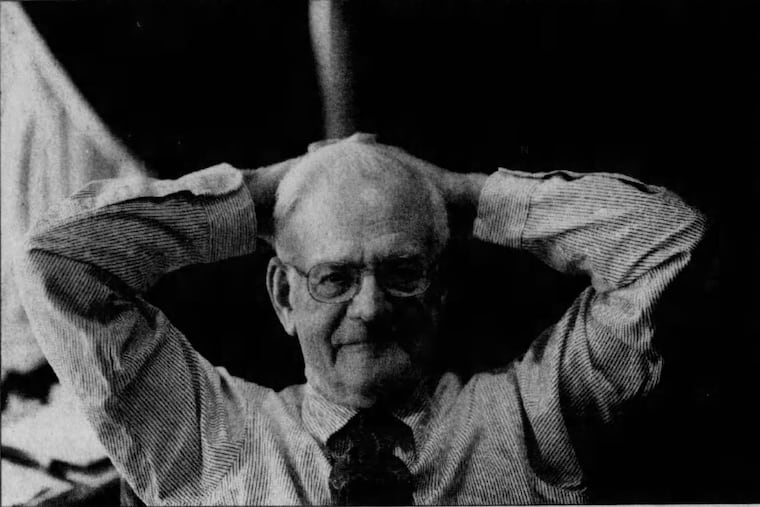

Louis C. Bechtle, Philadelphia’s former U.S. Attorney and chief federal judge, dies at 97

Judge Bechtle oversaw high-profile cases nationwide, including the Las Vegas MGM Grand Hotel fire and the denaturalization of a Ukrainian immigrant accused of assisting the Nazis.

Louis C. Bechtle, 97, an Army veteran who served as the United States attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania and later as the court’s chief judge, died Sunday, Dec. 22, in an assisted-living facility in Audubon, Montgomery County, following a short stay in hospice.

Throughout his three decades on the bench, Judge Bechtle presided over high-profile cases. He mediated the settlement in the 1980 fire in the Las Vegas MGM Grand Hotel that killed 87 people, and a $3.75 billion settlement to resolve thousands of lawsuits related to side effects from diet pills.

He oversaw the nation’s first racketeering trial of a sitting federal judge and stripped the citizenship of a Ukrainian man who lied about his collaboration with Nazis.

But Judge Bechtle’s legacy is also in the nearly 40 clerks he hired and trained, a community that he maintained throughout the years — and that continues to shape Philadelphia’s legal landscape.

“The judge was awe-inspiring to me,” said Carl W. Hittinger, who leads the antitrust practice at the BakerHostetler firm. “He was our guiding light.”

Judge Bechtle was born in Germantown in 1927 and grew up in the neighborhood through the Great Depression. At age 16, as World War II was raging, he dropped out of high school to join the U.S. Merchant Marine, an auxiliary force that allowed teens.

After the war ended, he returned to Germantown High School and after graduation enlisted in the U.S. Army, serving in Japan in 1946 and 1947. Upon his return to Philadelphia, using opportunities unlocked by the GI Bill, Judge Bechtle enrolled in Temple University for his undergraduate and law degrees.

» READ MORE: Stephen A. Cozen, founder of Cozen O’Connor law firm, has died at 85

After law school, Judge Bechtle worked for three years as a federal prosecutor in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. He spent most of the 1960s in private practice in Philadelphia and Montgomery County.

In 1969, then-President Richard Nixon’s administration appointed Judge Bechtle as U.S. attorney in the district where he served as an assistant U.S. attorney a decade prior. As the chief federal prosecutor for the Philadelphia area, he oversaw the prosecution of organized crime and illegal gambling operators.

His office also led an investigation into corruption in the mortgage insurance program for low-income homebuyers administered by Philadelphia’s branch of the Federal Housing Administration, which was unusual for the time. Following a 1971 Inquirer investigation, Judge Bechtle directed a prosecutor, Malcolm L. Lazin, to launch an investigation into the alleged abuse.

Judge Bechtle instructed his prosecutors to look for the truth, “without fear or favor, whatever the backlash may be,” said Lazin, who is the founder of the LGBTQ rights organization Equality Forum.

“It‘s not what you think, but only what you can prove beyond a reasonable doubt,” Lazin recalled Judge Bechtle telling him.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office in Philadelphia had just over a dozen prosecutors at the time, Lazin said, and federal law enforcement was focused on bank robberies, not white-collar crime.

Judge Bechtle advocated for resources from other agencies. The effort resulted in the guilty pleas or convictions of nearly 20 real estate brokers, among other indictments, and became a national example on how to approach public corruption investigations.

In 1972, Nixon appointed Judge Bechtle as a U.S. District Court judge. He would go on to spend nearly three decades on the federal bench, becoming known for handling mass product-liability litigations, in which thousands of cases from the entire nation were consolidated to his courtroom. These included cases against diet pills and bone screw manufacturers.

He also oversaw high-profile trials that garnered national — and international — attention.

Judge Bechtle presided over the 1980 trial of Wolodymir Osidach, a Ukrainian immigrant accused of collaborating with the Nazis in their persecution of Jews as a police officer and translator, activities he lied about in his immigration forms.

The emotional trial included witnesses from Israel and recorded testimony from the Soviet Union, said Hittinger, who was Judge Bechtle’s clerk at the time. Judge Bechtle found that Osidach lied, and in 1981 ordered that his citizenship be revoked.

“That case is in the history book,” the former clerk said. “It still stands as one of the standards for deportation.”

Judge Bechtle also oversaw cases outside Philadelphia. He volunteered to preside over the civil lawsuits brought by victims of the 1980 fire in the Las Vegas MGM Grand Hotel, and worked out a settlement between the parties. He was later appointed by Supreme Court Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist to oversee the lawsuits following the 1986 fire in the Dupont Plaza Hotel in San Juan, Puerto Rico, that killed 97.

The long list of cases Judge Bechtle heard covers nearly every aspect of life and law: drugs and medical devices’ side effects, airplane crashes, a California federal judge’s corruption, racial discrimination in an engineers union, drug-trafficking, and protection of birds.

In 1990, Judge Bechtle was elevated to chief judge in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, a position he held for three years.

Judge Bechtle’s clerks remember him as a mentor who led by example.

As an attorney in private practice, Hittinger invited Judge Bechtle to his daughter’s bat mitzvah. The former clerk had a case in front of the judge at the time, so Judge Bechtle said he would come to the ceremony but not the reception — to avoid having an attorney with a pending case purchase a meal for him.

Kevin D. Kent, one of Judge Bechtle’s last clerks who is an attorney with Clark Hill, said the judge ran a tight courtroom. But he also had a dry sense of humor.

Judge Bechtle remembered his roots from Germantown and was unimpressed by lawyers using big words. Kent recalled a time in which an attorney kept using the word sophistry during a hearing. Judge Bechtle interrupted the attorney and asked him to define it. The lawyer couldn’t, and Kent had to stop himself from laughing.

Judge Bechtle retired from the federal bench in 2001 and joined the Conrad O’Brian firm in Philadelphia. Kent followed in his footsteps, and routinely stopped by Judge Bechtle’s office to share how he planned to approach cases.

“He’d have his wonderful way about him when he’d say, ‘That’s an interesting approach, but how about you do the exact opposite and tell me how it goes,’” Kent said. “And he was always right.”

Judge Bechtle’s daughter, Amy Bechtle Peacock, remembers her father for his humor, love for music, and the family’s summers in Ocean City, N.J.

“Our house was full of laughter, because he was a riot, and our house was full of music,” she said.

Her father often told her that without the GI Bill he wouldn’t have had such an illustrious legal career. And as he hired clerks, he focused, on talented graduates from local schools who might not have gotten chances elsewhere.

“He is really a rags-to-riches story,” Bechtle Peacock said.

» READ MORE: Perry S. Bechtle, lawyer and WWII veteran

Judge Bechtle was predeceased by his first wife, Helen O’Donnell, and his second wife, Margaret “Beckie” Beck. He was also predeceased by his brothers, attorney Perry S. Bechtle and artist C. Ronald Bechtle, and a stepdaughter, Joanne Finney.

He is survived by his children Barbara Bechtle, Nancy Bechtle Anderson, and Amy Bechtle Peacock; stepchildren Tara Finney, Samuel Finney Jr., and Lynn Finney; eight grandchildren; and 13 great-grandchildren.

A private memorial service will take place in the coming weeks. The family asked that in lieu of flowers, contributions be made to the Honorable Louis C. Bechtle Scholarship at the Temple University Beasley School of Law.