Mark Hollis, singer who led influential rock band Talk Talk, dies at 64

Mark Hollis, a singer and songwriter who led the critically acclaimed British band Talk Talk, which veered from synthesizer-heavy pop to a haunting and influential medley of new wave, punk rock, free jazz, classical, blues, folk, and ambient music, has died. He was 64.

Mark Hollis, 64, a singer and songwriter who led the critically acclaimed British band Talk Talk, which veered from synthesizer-heavy pop to a haunting and influential medley of new wave, punk rock, free jazz, classical, blues, folk and ambient music, has died.

The death was confirmed Tuesday by his longtime manager, Keith Aspden, who said Hollis "died after a short illness" but did not provide additional details.

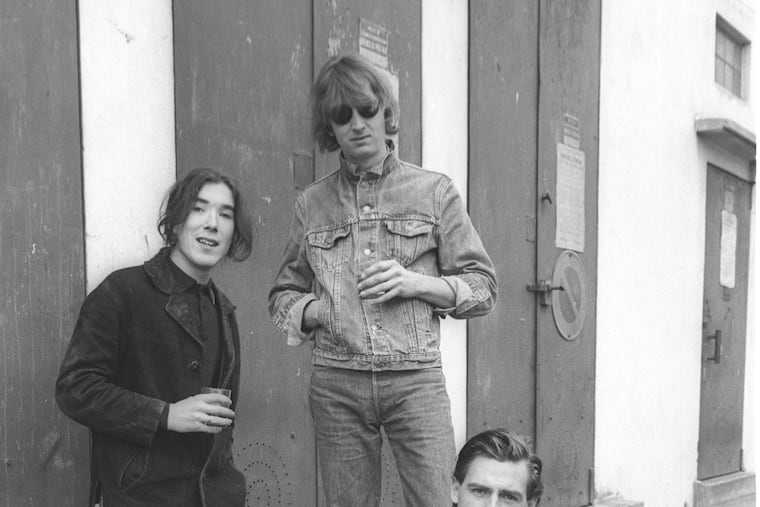

Formed in 1981 by Hollis, bassist Paul Webb, drummer Lee Harris, and keyboardist Simon Brenner, Talk Talk was initially viewed as a potential rival to Duran Duran, the clean-cut British group with a buoyant, synth-based sound.

But under Hollis, a plaintive-voiced singer who counted free-jazz artist Ornette Coleman and bluesman John Lee Hooker as major influences, Talk Talk became a genre-blurring band like few other acts in pop music. His former bandmate Webb, who performs under the name Rustin Man, wrote in an Instagram post that Hollis "knew how to create depth of feeling with sound and space like no other."

As the group’s principal songwriter, Hollis infused early electronic hits like “Talk Talk,” “Such a Shame,” and “Life’s What You Make It” with hints of anxiety and gloom, singing of “the dice behind my fate” and “this eagerness to change” while backed by throbbing bass lines and soaring melodies on the synthesizer.

The band sold millions of records and broke into the U.S. Top 40 in 1984 with “It’s My Life,” later covered by singer Gwen Stefani’s band No Doubt. And with the release of its third album, an adventurous pop record titled The Colour of Spring (1986), Talk Talk seemed on the verge of becoming an international phenomenon. They effectively received free rein from their record label, EMI, to make their next album.

Decamping to a former church in London, Hollis and his bandmates spent a year crafting the six-song Spirit of Eden (1988), a record that sounded so different from their previous work that EMI sued the artists, arguing that the album was insufficiently commercial. (The case was thrown out, according to the Guardian.)

Songs such as “I Believe in You” — written for Hollis’ older brother Ed Hollis, who struggled with heroin addiction — featured dramatic shifts in tone and volume, crescendoing from a quiet hum to a drum-heavy roar. Phrases, and sometimes even single notes, were drawn from hours-long sessions with oboe, harmonica, and violin players, who were instructed to improvise while playing in total darkness or in the glow of candles, psychedelic lamps, or strobe lights.

"They crafted an immersive and ever-flowing style, alternately hushed and loud, lush and arid," Jess Harvell wrote in a retrospective review for the music website Pitchfork. "It was a brand of unashamed art rock that was completely out of step with both the underground's unkempt roar and the manicured mainstream."

Hollis announced that because of its complex production, the album would not be supported by a tour. He also planned to release no singles. Still, he and his songwriting partner Tim Friese-Greene, a producer and multi-instrumentalist who served as an unofficial fourth member of Talk Talk, expected that the record would sell millions of copies.

"We thought we'd broken the mold and could turn the tide of history by going back to a world where the single wasn't king," Friese-Greene once said. "How sadly mistaken we were."

The album sold a relatively meager 500,000 copies and was described by a Q magazine reviewer as “the kind of record which encourages marketing men to commit suicide.” But Spirit of Eden and its follow-up — the similarly experimental Laughing Stock (1991) — have since acquired the status of rock masterpieces. The records are often credited with paving the way for experimental post-rock groups such as Sigur Ros, Radiohead, Spiritualized and Explosions in the Sky.

Talk Talk fractured amid the intense recording process of those albums, with Webb leaving after Eden and the band folding for good after Laughing Stock. Hollis released a solo album titled with his name in 1998, with songs that built on the spare acoustic sound he had developed with Talk Talk, before effectively retiring from the music business.

He gave few interviews, seeking to place the focus squarely on his art. “I hope in the end to be understood for the music I do decide to put out, and [for the] meaning and sense the music has,” he told the British magazine Melody Maker in 1991. “It’s almost useless asking me questions about it. The music speaks for itself.”

Mark David Hollis was born in the Tottenham section of London on Jan. 4, 1955. He said he was studying to become a child psychologist when he dropped out of college in the mid-1970s and went on to form a London-based band called the Reaction.

One of its songs, “Talk Talk Talk Talk,” appeared on the influential punk compilation Streets, released in 1977 by Beggars Banquet. After the Reaction disbanded, the song inspired the name of Hollis’ new band, which came together after his older brother, a producer and manager of the rock group Eddie and the Hot Rods, introduced him to a new set of musicians. Brenner, the keyboardist, left after the group’s first album.

Hollis said he wanted only to write and record music, and professed to have little interest in music videos, live performances or the trappings of stardom. When he shot a video for “It’s My Life,” he refused to lip sync, and pursed his lips while standing at a zoo; EMI later ordered the video reshot, according to the Guardian, and Hollis muddled his way through.

As relations between Talk Talk and EMI broke down in the aftermath of Spirit of Eden, Hollis sued the label when it released a remixed compilation of Talk Talk songs, History Revisited (1991), without the band’s consent. The album was ultimately pulled from circulation, and Talk Talk recorded its final record with the jazz-focused label Verve.

Harris was married and had two children, and after releasing the solo album Mark Hollis — in part to fulfill a contract obligation with Verve, he said — he announced that he was retiring from music to focus on his family.

A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

His solo effort marked a culmination of a yearslong move toward minimalism. He had once professed to prefer silence to music, and the album’s recording process was so quiet that the record included the sounds of a creaking guitar stool and footsteps in the studio.

His aim, he told the Times of London, was “to produce a piece of music so that it was impossible to know in which year it was recorded.”