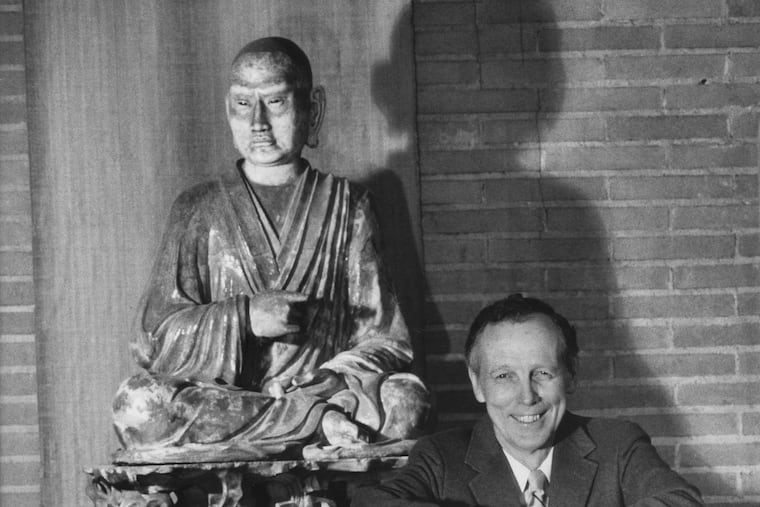

Robert H. Dyson Jr., 92, former head of Penn Museum, dies

The dogged archaeologist made one of the profession’s most spectacular and unexpected finds during a 1958 University of Pennsylvania excavation in Iran. He was the Penn Museum's director from 1982 to 1994.

Robert H. Dyson Jr., 92, a dogged archaeologist who made one of the profession’s most spectacular and unexpected finds during a 1958 University of Pennsylvania excavation at Hasanlu in northwestern Iran, died Feb. 14 in Williamsburg, Va., after a long illness.

Mr. Dyson spent more than 20 years excavating the Hasanlu site for Penn’s University Museum of Art and Archaeology with colleagues from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Archaeological Service of Iran.

The team unearthed vast quantities of artifacts and richly suggestive layers of an unknown and sophisticated city, embodied in Mr. Dyson’s dramatic find of what is known as the Golden Bowl of Hasanlu.

But to Mr. Dyson, a serious if not taciturn scholar, the bowl was known simply as, “Baby.”

The find came at a site, located in the remote Iranian northwest, that had been destroyed by attackers around 800 B.C. Mr. Dyson uncovered the remains of an Iron Age warrior who was clutching the bowl, covered with intricate scenes incised on its gleaming surface by highly skilled artisans working in the 12th century B.C.

Returning season after season, Mr. Dyson and his colleagues eventually uncovered a whole architectural complex, and the story of Hasanlu became more mysterious and dark. Who set fire to the complex in the long ago, trapping 200 people in collapsing debris and ash? Were the arms that clutched the Golden Bowl those of an attacker or defender of the site? Why were bodies hacked so brutally?

Did Hasanlu fall in a raid, or was there something larger and more sinister afoot?

And always, the great archaeological questions: Where did they come from, where did they go?

Mr. Dyson labored over the site in field expeditions until 1977 and turned his considerable attention to the equally daunting — and still incomplete — task of publishing the Hasanlu findings, a vast conglomeration of data and artifacts and interpretation.

“It’s just overwhelming, I think," said Richard Zettler, associate professor of Near Eastern languages and civilization and head of the Penn Museum’s Near East section. He was hired by Mr. Dyson in 1986. “There’s a whole lab full of Hasanlu field records.”

“He told me that if he hadn’t found that Golden Bowl he’d be selling socks in Wanamakers," Zettler recalled.

In 1979, Mr. Dyson was named Penn’s dean of faculty for arts and sciences, and in 1982, he became director of the museum, staying in that position until retirement in 1994.

“He had a vision of what he wanted the museum to be,” said Zettler. “He saw it as a very serious research institution.”

Toward that end, Mr. Dyson was a firm supporter of research expeditions, telling Zettler at one point: “Your job isn’t to teach. Your job is to dig for me.”

In that spirit, Mr. Dyson became a firm backer of students and their projects. “He believed in sending members of the museum into the field,” said Zettler. “He produced a lot of Ph.D.s.”

Indeed, museum officials likened the field rosters of the Hasanlu project to “a who’s who of the archaeology of Africa, Europe, and Asia.” Mr. Dyson deployed his mentorship and support with largesse, supporting "excavations all over Iran,” said Zettler. “He was a seminal figure.”

Mr. Dyson was born in York, Pa. He received his B.A. in 1950 and Ph.D. in 1966 from Harvard, specializing in Near Eastern archaeology.

He came to Penn in 1954 as an assistant professor in the anthropology department and assistant curator in the museum’s Near East section. After leading the Penn Museum’s Tikal project in Guatemala in 1962, he was promoted to professor and became head curator of the Near East section in 1967.

Much honored, Mr. Dyson was president of the Archaeological Institute of America from 1979 to 1981, president of the American Institute of Iranian Studies in 1968 and from 1987 to 1989, and a member of the Society of Fellows at Harvard, the American Philosophical Society, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

He received honors from the Athenaeum of Philadelphia and the Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, and was a decorated chevalier of the Ordre des Artes et des Lettres (France). He was awarded the Order of Homayoun (4th Rank) by the Shah of Iran in 1977.

A memorial service is being planned for the fall at the Penn Museum.