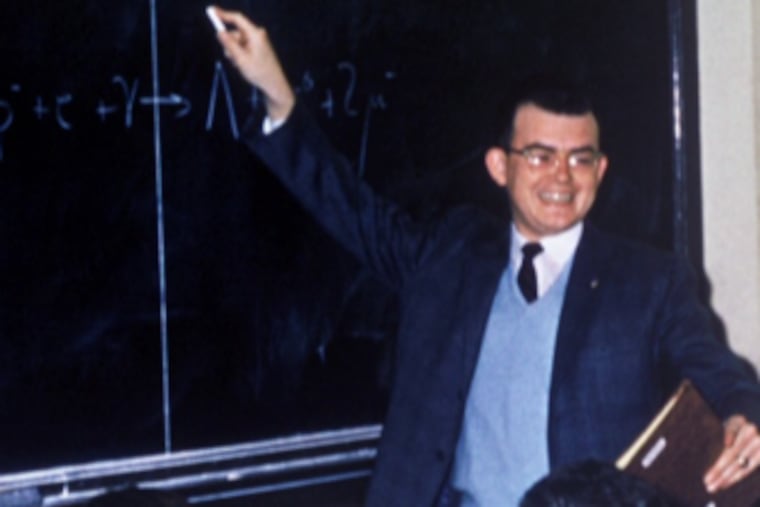

Thomas J. Devlin, pioneering particle physicist and popular Rutgers professor emeritus, has died at 87

The winner of a 1994 prize for his work on subatomic particles and a 2017 award for his mentorship, he encouraged "original ideas for new analyses" and "experimental techniques," a colleague said.

Thomas J. Devlin, 87, of Philadelphia, pioneering particle physicist, popular professor emeritus at Rutgers University, and award-winning mentor, died Sunday, Oct. 2, of kidney disease and congestive heart failure at the Quadrangle retirement community in Haverford.

For more than four decades, Professor Devlin used particle colliders and other sophisticated equipment to study high-energy physics and the nature of mass and matter. He taught and researched in the department of physics and astronomy at Rutgers from 1967 to 2007, spent 1970 at the European Center for Nuclear Research in Geneva, Switzerland, and discovered what he called a “gold mine” of scientific information in 1975 at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Ill.

He won a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship in 1991, was at the Fermi lab in 1995 when physicists discovered the top quark, and shared the American Physical Society’s 1994 W.H. Panofsky Prize with Lee Pondrom for their groundbreaking work on subatomic particles known as hyperons.

He conceived, directed, and participated in numerous projects that involved hundreds of institutions and physicists all while teaching undergraduate and graduate classes in physics, astronomy, engineering, premed, and biology. Convinced that collaboration between students and instructors was vital to both education and discovery, he wrote in the New York Times in 1995 that “the best way to learn science is to spend time with scientists doing science.”

Students said his leadership, positive attitude, sense of humor, hard work, and collegiality “made doing physics a lot of fun” and “like an exciting and challenging game.” He routinely invited colleagues to his home for dinner and discussions, and a diagram of his academic tree includes dozens of scientists he mentored as they advanced from graduate students to experienced researchers.

He especially advocated for women in science and won a 2017 mentoring award from the American Physical Society’s division of particles and fields for “his leadership by example, in studying new ideas, accepting all questions, and creating an inclusive environment.”

In a tribute, a female colleague said: “I think that I can safely say that, in addition to my parents and husband, there is not a single person who influenced the career that I have today more than Tom Devlin.” Another female colleague said: “He treated everyone with respect and created an environment that encouraged collegial and professional behavior in everyone. Women and men were treated equally as were students, postdocs, and senior faculty.”

He taught at Princeton for five years before Rutgers, was a fellow at the American Physical Society, and became a visiting faculty member in the department of physics and astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania after his retirement. He wrote papers, earned grants, and, after shifting into astrophysics in the early 2000s, worked at the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia observing other galaxies.

“He was incredibly smart, hardworking, and dedicated to getting the job done,” said his son Mark. “Because of that he accomplished a great many things.”

Born Aug. 23, 1935, in Jenkintown, Thomas Joseph Devlin became interested in science as a boy and wondered on the playground why birds and airplanes fly but he couldn’t. He graduated from La Salle High School and earned a bachelor’s degree in physics and math from La Salle College, now La Salle University, in 1957.

“I was a sponge,” he said in a short summary of his life, “soaking up everything I could read about math and science.”

He went to the University of California, Berkeley, met like-minded physicists, and gained a master’s degree in 1959 and a doctorate in physics in 1961. He met psychology student Nancy Sherry, and they married in 1962, and had sons Paul, Tom, and Mark. She died in January.

Professor Devlin and his family traveled throughout Europe during his time in Geneva, and he enjoyed the Philadelphia Orchestra and ballet. He had a stroke in 2007 and moved with his wife from North Jersey to Center City.

In 2017, he said: “I’m pretty smart, but all my sons are smarter. I have a happy life, and it is continuing.”

In addition to his sons, Professor Devlin is survived by five grandchildren, a brother, and other relatives.

A celebration of his life is to be held later.