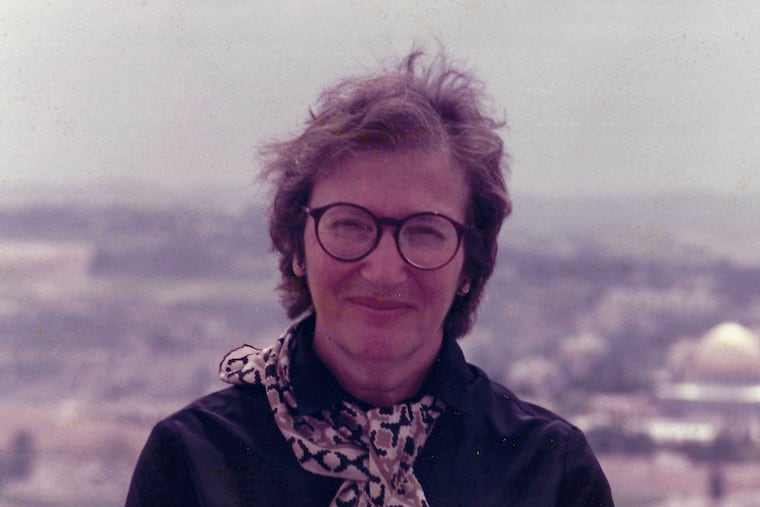

Anita Summers, pioneering Wharton School economist, has died at 98

She pioneered the idea that Federal Reserve regional bank economists should work on local and regional issues, said her son, Lawrence, a former U.S. Treasury Secretary.

Anita Arrow Summers, 98, a pioneering economist and longtime Lower Merion resident who taught at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and worked at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, died Sunday, Oct. 22, at home after a monthlong illness.

“We were more likely to discuss inflation at the dinner table than other families,” said her son, Lawrence Summers, who served as U.S. Secretary of Treasury under President Bill Clinton.

Ms. Summers’ first job as an economist was working for one of the Standard Oil Co. successors, where “her new boss said to her, ‘I figure I am getting the same brains for less money,’” because women were paid less than men, according to Sheryl Sandberg, a former Facebook executive who chronicled Ms. Summers’ career in her 2013 best-selling book, Lean In. Such were the times that “she thought it was a compliment,” Sandberg said. But Ms. Summers also demanded — and got — unprecedented access to report directly to top executives.

Sandberg got to know Anita Summers while working for Lawrence H. Summers at Harvard University, the World Bank, and in the U.S. Treasury Department.

“She was an incredibly accomplished professional” at a time when women on college business faculties were rare, Sandberg said, “and a remarkable mother,” who gave “a lifelong example” of how to balance and excel.

The daughter of immigrants from Romania, Anita Arrow earned her bachelor’s at Hunter College in 1945 and a master’s at the University of Chicago in 1947, and later studied in a doctoral program at Columbia University. She married fellow economist Robert Summers in 1953. The family moved to the Philadelphia area eight years later, when he landed a teaching job at the University of Pennsylvania.

Ms. Summers raised their three sons to school age, then began teaching economics at Swarthmore College in 1967. In 1971, she joined the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, heading its urban economics unit.

“She pioneered the idea that Federal Reserve regional bank economists should work on local and regional issues,” Lawrence Summers said.

On her watch, officers at the bank, which among its duties serves as a regulator to banks based in eastern Pennsylvania, South Jersey and Delaware, began taking seriously the controversial Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, which required commercial banks to make loans available in poor neighborhoods of any community where they did business.

With a team at Wharton’s real estate center, “Mom did early work on zoning restrictions,” which she considered “pernicious” because they “made the price of housing high by restricting development,” Lawrence Summers said. “She also testified in a number of educational equity lawsuits. She developed ways to measure education by value-added, as opposed to seeing education as a static achievement.”

She moved in 1979 to Wharton, where she revived the school’s long-dormant public policy studies program, forming a department she came to chair. Her books included Economic Development Within the Philadelphia Metropolitan Area, with Thomas F. Luce, published by Penn’s university press in 1987, and Urban Change in the United States and Western Europe: Comparative Analysis and Policy, with two coauthors, published by the Urban Institute in 1999.

Among the problems she studied was Philadelphia’s decline as an economic and population center, which she concluded was affected by its tax and regulatory schemes.

“She was very focused on making government more effective,” her son said. “She felt the city tended not to be well governed and that it was more a matter of governing better, than governing less.”

From 2001 to 2003, Ms. Summers served as Penn’s ombudsman, tackling difficult issues including sexual harassment allegations involving university staff.

She came from a family of economists, whom her son characterized as “practical progressives,” believing as she did that effective government leaders could use carefully collected data and other evidence to develop policies that helped people prosper more easily.

Her husband’s brother, Paul Samuelson, wrote economic textbooks and her own brother, Kenneth Arrow, was an economist, mathematician and political theorist. Her husband, Robert, who died in 2012, did groundbreaking work on data estimates.

“She told me to do the right thing and do it as well and as passionately as you could, whether it was raising your children, teaching your students advocating the policies you preferred, or trying to get legislation passed,” Lawrence Summers said. She set an example for “doing everything one could as well as one could and living life to the fullest.”

In addition to her oldest son, Ms. Summers is survived by her sons John Summers, a partner at the Hangley Aronchick law firm in Philadelphia, and psychiatrist Richard Summers. She had seven grandchildren.

Services were Wednesday, Oct. 25, at Beth David Reform Congregation, Gladwyne.