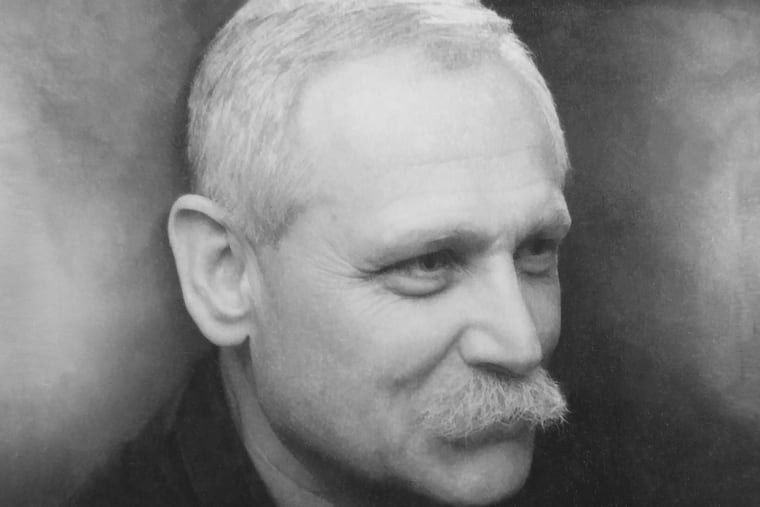

William Larson, 76, artist who bent the rules of static photography to foreshadow digital art

Mr. Larson started out working in a commercial art studio, but his experiments with the medium took him far afield.

William G. Larson, 76, of Chestnut Hill, an artist who bent the rules of static photography to explore the concept of time, and whose incorporation of fax and teleprinter sounds and text into his early work anticipated digital art, died Thursday, April 4.

Mr. Larson died at home of complications from Parkinson’s disease, said his wife, Sally G. Larson. He had lived with Parkinson’s and dementia for the last decade.

“It’s a great sadness that during the last decade of his life, a time when he would otherwise have been articulating his thoughts and ideas summarizing all that he was, he was instead held prisoner by these cruel diseases,” she said.

Born in North Tonawanda, N.Y., Mr. Larson earned a bachelor’s degree from the State University of New York at Buffalo in 1964 and a master’s degree from the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago in 1968.

He worked for a commercial photography studio in Chicago until he completed his degree and was hired to establish the photography program at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art.

Within five years, he added a graduate division that became one of the top photography programs in the country. Mr. Larson was among the first to insist that formal courses in color be included in the core photography curriculum.

In 1988, he was appointed director of the graduate photography/digital imaging program at Maryland Institute College of Art, where he remained until retiring in 2006.

His work as an artist was ambitious and complicated to the layman’s eye.

“A constant focus of [my work] was the challenge to conceptualize ‘time’ through the essentially static medium of photography,” Mr. Larson said in an explanation of his work.

An early experiment was Figure in Motion. In 1966, Mr. Larson modified a Hasselblad camera with a clock motor to mechanically advance the film at 1 rpm for a nine-minute exposure, as his subject rotated 360 degrees.

Each rotation provided a simultaneous view of all sides of the subject. The result was a time-based static photographic print with an elongated appearance.

Other experimental work included Fireflies, pictures made in the late 1960s with then state-of-the-art fax technology. The electronic montages included photographic, text, sound, voice, and musical elements. Produced using the coded program of the Graphic Sciences DEX 1 Teleprinter, they were some of the first images produced electronically.

Vince Aletti, who reviewed a 2015 exhibition of the early work for the New Yorker, wrote: "These startling black-and-white images were made electronically four decades ago, using signals transmitted by fax machines. The combinations of pictures (hands, lips, a huge housefly), words (“press,” “play,” “prim,” “plan”), and overlapping lines of jittery static suggest concrete poetry illustrated by Robert Rauschenberg.

“Closer to drawing than they are to photography, Larson’s experiments foreshadowed the digital-image revolution to come and are all the more fascinating for their primitive grit."

In the 1970s, Mr. Larson was chosen to experiment with the SX-70 and 20-x-24 Polaroid cameras. In 1980, he was artist-in-residence at the University of Arizona, where he documented the urban landscape, resulting in his “Tucson Gardens” series.

In the 1990s, Mr. Larson began experimenting with video, redefining how an image might be made under a different set of criteria.

Between 2002 and 2012, Mr. Larson produced Film on Film, a series of photographs celebrating the end of the materiality of film. Curator Robert Sobieszek acquired several for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

His work is in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the J. Paul Getty Museum in California, and the San Francisco Museum of Art. It was included in the 1981 Whitney Biennial and a 1985 one-person show at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia.

When not teaching or in his art studio, Mr. Larson enjoyed fly-fishing.

In addition to his wife, Mr. Larson is survived by children Erika L. Cervantes and Michael Larson, and two grandchildren. His 1964 marriage to Rose Reynolds ended in divorce, as did his second marriage to Catherine Jansen.

Services will be private. Mr. Larson donated his body to medical science.