Memories of her Holocaust survivor father guided Amy Gutmann’s tenure as ambassador to Germany

Kurt Gutmann would have stood against appeasing Vladimir Putin, who wants to destroy Ukraine and weaken Western democracies.

The last thing former University of Pennsylvania president Amy Gutmann ever imagined was becoming U.S. ambassador to Germany, the country from which her Orthodox Jewish father barely escaped with his life.

Born in the tiny town of Feuchtwangen in Franconia, 23-year-old Kurt Gutmann realized shortly after Adolf Hitler came to power that he had to flee his homeland once he saw his formerly friendly Christian landlord give the Nazi salute. Gutmann made it to India, started a metal factory, and managed to rescue his parents and all four siblings — two of whom had already been sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp.

“My dad died when I was 16 and I always asked how I could live up to my father,” Gutmann told me recently. We met in her new office at Penn’s Annenberg School for Communication, to which she returned this summer after more than two years in Berlin.

“So when I was asked to be ambassador to Germany,” she recalled, “I said to myself, ‘I have to do it,’ even though I had never planned for this. Yet in some sense I had prepared because my whole scholarship has been about defending democracy and not letting tyrants take over.”

As she waited to present her credentials to German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier on Feb. 17, 2022, she thought, “What would my father have thought to see me sitting in the presidential palace?” Then Steinmeier told her, “how meaningful it was to him that my father’s daughter was the new ambassador. It took all my strength not to cry.”

What Gutmann could never have imagined when she accepted the position was that one week after meeting Steinmeier she would be enmeshed in the greatest challenge to Western democracy since World War II: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Or that she would be involved in the biggest shift in relations between Germany and the U.S. since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

From the moment she arrived in Berlin, she was at the center of this drama, which has reached a climax with the reelection of Donald Trump who wants to cut aid to Ukraine. Thoughts of her father ran through her mind every day of her ambassadorship. They color her views of how to save Western democracy and the U.S. European alliance today.

Four days before Russian President Vladimir Putin sent his troops into Ukraine, Gutmann was being driven down the Autobahn at more than 110 mph to meet Vice President Kamala Harris, along with top German and European officials at the high-level Munich Security Conference. She was there to help deliver declassified U.S. intelligence that an invasion was imminent. One senior German official told her: “How can you believe Putin would be so irrational as to invade?” She replied, “How can you not believe that someone with absolute power would be tempted?”

“We thought that unless we could get the Europeans with us,” Gutmann explained, “Putin would decimate Ukraine. There was no reason to believe if we went it alone, we could enable them to resist.”

Germany delivered. On Feb. 27, only three days after the start of the war, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz made a historic speech stating that the Russian invasion was a turning point — a Zeitenwende — in European history and German foreign policy. For decades, Germany had relied on increased economic ties with Moscow to preserve peace with Russia, notably with the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline deal. The invasion was a wake-up call for Berlin.

Scholz, whose Social Democratic Party was historically pacifist, recognized that Germany could no longer assume war had been banished from Europe, or that it could rely mainly on the U.S. defense umbrella. The chancellor announced an end to the Nord Stream 2 contract, and a plan to modernize the German military and spend over $100 billion to do it, along with a commitment (now fulfilled) to meet the NATO target of 2% of GDP for defense spending.

“It was truly a historic turning point,” Gutmann said. After a rocky start — when Berlin offered only to send 5,000 helmets to Ukraine — Germany has become the second-largest contributor of military aid to Kyiv, the largest contributor of humanitarian aid, and host to one million Ukrainian refugees.

“Germany went from being one of our biggest problems vis a vis Putin to lock step together with the United States,” she said. “I saw a huge shift in thinking from Russia as benign to Russia as an existential threat to Germany.”

During her tenure, Moscow upped its criminal operations inside Europe, including in Germany. From assassinations on Russian exiles, including one in a Berlin park, to cutting key European pipelines, engaging in massive disinformation campaigns and cyberwarfare, and serious efforts to manipulate European elections. There was even a thwarted attempt to murder a top German businessman.

“Russia clandestinely acts as a terrorist organization against the United States and its allies,” Gutmann said. “The only way we can defend against this is by sharing intelligence with key European partners. I saw firsthand how critical this sharing was.”

While she was ambassador, “Eighty percent of Congress came through Germany, many to my dining room with German officials, a lot of Republicans as well as Democrats, and to a person they were all pro-Ukraine,” she said.

What encouraged her further was a Germany whose democratic institutions have withstood the Russian challenge, so far. “The biggest and most basic bulwark against German extremism,” she told me, “is the robust system of civic education.”

Something, I’d add, that Americans can only dream of.

“Every schoolchild takes required courses in the history of the Holocaust, of antisemitism and all forms of hatred and bigotry,” Gutmann noted. “They identify support for Ukraine as a way of defending their own freedoms and democracy.”

About 80% of Germans oppose the far right, anti-Ukraine, pro-Putin Alternative für Deutschland (AFD) party, she says; leaders in all four leading parties have agreed not to form a coalition with the AFD when Germany next holds elections in February. Any likely coalition will assuredly continue to support Ukraine. (I believe a conservative-led coalition might even be more willing to send Kyiv its much-desired Taurus missiles, now that the U.S. has authorized use of American-made long-range ATACMS on Russian soil.)

“They won’t turn back,” Gutmann said about German support for Ukraine. “Will we?”

She referred of course to German angst about the result of the U.S. presidential election and the very real possibility that President-elect Donald Trump will cut off aid to Ukraine if it won’t capitulate to Putin.

When I asked if Europe could go it alone in helping Ukraine push Russia back, perhaps led by Germany, her answer was sharp and simple: No.

Although Europe gives more aid than we do to Ukraine, it doesn’t have the weapons production capability or key systems that only the U.S. can deliver. Nor has it succeeded in unifying weapons production systems between key countries. Moreover, added Gutmann, “Germany doesn’t want to lead alone” because of its history, nor does it have U.S. backing to do so. “Europe alone cannot win against a rising flood tide of autocratic aggression,” she said.

If Putin is permitted to swallow Ukraine, he will seek to undermine the United States (irrespective of any bromance with Trump) and threaten allies with expansion. What Germans fear most, is that he will start with Moldova, Poland, and the Baltics, then move on from there. Without U.S. backing, the strongest defensive alliance in history, NATO, would come apart.

“We would be foolish to underestimate the Russian level of threat to democracies,” Gutmann insisted.

“Europe has long taken its cues from the U.S for security and on outside aggression,” Gutmann explained. “If Europe has to go it alone, Ukrainian democracy loses out big time to Russia’s brutal, unprovoked aggression. Energy prices rise, democratic security declines worldwide. Never has the need for allies been greater.”

“We allies must hang together,” she added, paraphrasing Benjamin Franklin, “or assuredly we will all hang separately.” Germany’s anxious query is whether this matters to Trump.

That question turns Gutmann’s thoughts again to her father.

“He would say inaction and silence is injustice. We have to combat Putin. We have to make sure he doesn’t win.

“He would be amazed that Germany has become one of our best allies and would insist that we not give that up.

“He would say Ukraine is fighting for freedom like those who fought the Fuehrer. Ukraine is fighting for its democracy and ours.

“Once it’s too late, it’s too late [to confront autocrats or dictators]. It’s not too late now.”

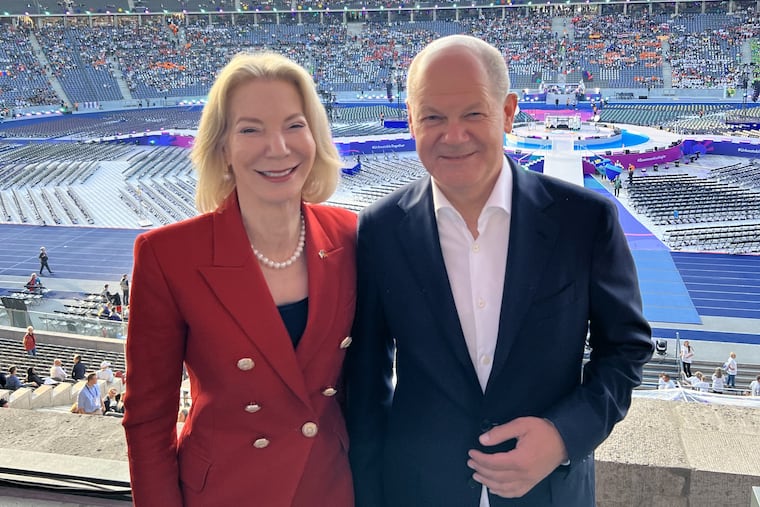

Editor’s note: A previous version of this column included a photo with an incorrect image credit. It was take by Michele Tantussi/AFP.