Yes, ‘bacteria,’ ‘data,’ and ‘agenda’ are all technically plural. But don’t be annoying about it.

I’m not saying that English speakers can’t say "datum" if they want. Call a meeting to tell everyone and send out an agendum for it. Fill multiple stadia with people whom you want to tell.

Every time you think Latin is dead, it rears its ugly zombie head again, gnashing its gnarly prescriptivist teeth and reviving revolting revenants of language.

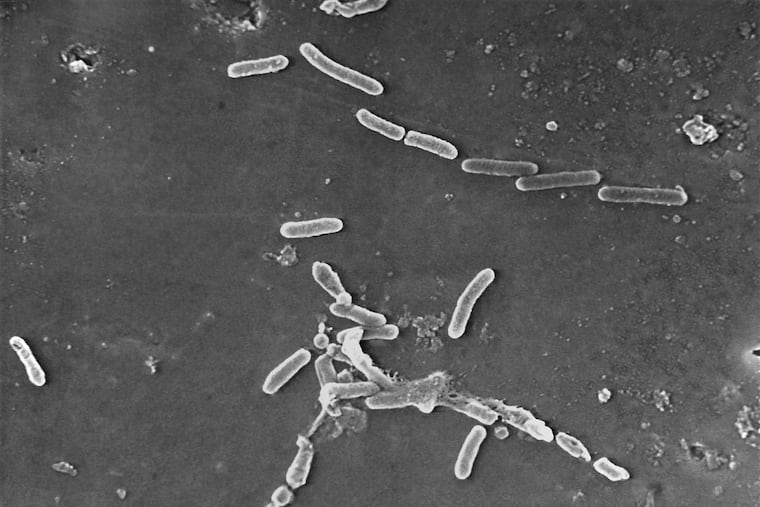

Sometimes literally: Two weeks ago, Clorox fired the latest Latin salvo with its recall of Pine-Sol scented multi-surface cleaners due to “risk of exposure to bacteria.”

Even though Clorox’s usage of the word bacteria was uncontroversial, the company invoked a term that makes the undead Latinists take up their arms.

» READ MORE: Clorox recalls cleaning products that might contain bacteria

When it’s used in the singular, bacteria is one of those words that many love to get agitated about. They cry that bacteria is plural, and bacterium should be used in the singular — just as it is in Latin.

Technically, the Latinists are correct. But also technically, they’re zombies who are devouring the English language whole — and then complaining that it doesn’t taste as good as Latin does.

We got a lot of the English language — anywhere from half to two-thirds of it — from Latin. I took five years of Latin in school, which helps explain why I am the way I am. And while plenty of words have transferred unadulterated from Latin (agenda, data, criteria), many other words have transmogrified as they passed through French, Spanish, Italian, etc. As they should. Different languages use different words.

So why do some get so upset that English speakers aren’t following Latin rules when speaking the English language?

Since it’s become prevalent in English, bacteria has evolved to be acceptable as either singular or plural. Take it from recent Pine-Sol-related stories on CNN (“Roughly 37 million bottles of Pine-Sol products have been recalled because they could contain a potentially harmful bacteria”), the New York Times (“the bacteria is resistant to nearly all antibiotics”), or the Wall Street Journal (“The bacteria usually doesn’t affect people with healthy immune systems”) (all emphasis added).

That’s not a global copyediting breakdown, but rather a reasonable set of data showing that bacteria works just fine in the singular.

Bacteria has evolved to be acceptable as either singular or plural.

I’m not saying that English speakers can’t use bacterium. The word is both correct and comprehensible, even if it is a bit pretentious. But if you don’t mind that look, that’s on you. Call a meeting to tell everyone and send out an agendum for it. Fill multiple stadia with people whom you want to tell.

However — and here’s where I make a bunch more of you angry — if you’re OK with using words like agenda in the singular, then you also have to be OK with not just singular bacteria (as CNN, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal are), but also singular data.

Why wouldn’t you? Both agenda and data came from Latin around the same time, in the first half of the 17th century, but saw their usage grow dramatically in the 20th century. Perfectly reputable sources (like the New York Times, NPR, and Pew) use the singular data all the time. But for some reason, many are more protective of keeping data plural than they are of a plural agenda.

You might have learned in school that you’re not supposed to split infinitives, also known as “to” forms of verbs: to be, to walk, etc. “To boldly go” was considered wrong. The reason behind this asinine “rule”? Because each of those “to” verbs is a single word in Latin (“to be” is esse; “to walk” is ambulare). Because a single word literally can’t be split, some old-school teachers said you shouldn’t be able to do that in English either.

Fortunately, that rule has mostly gone by the wayside. Even the stodgy Modern Language Association now says it’s OK to split infinitives.

Latin died a long time ago. Let it rest in peace — undead isn’t a good look for anyone.

The Grammarian, otherwise known as Jeffrey Barg, looks at how language, grammar, and punctuation shape our world, and appears biweekly. Send comments, questions, and genitive case to jeff@theangrygrammarian.com.