In Philadelphia, Irish civic leaders discuss Brexit’s harsh impact on their homeland | Trudy Rubin

Eisenhower fellows detail the threats Brexit poses to the Good Friday peace accord and why it must be saved.

In Philadelphia this week, a group of Irish men and women are gathered, reflecting the success of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement in bringing peace to Northern Ireland.

But they worry that a looming Brexit — and the British parliament’s hapless efforts to exit the European Union — are already threatening Ireland’s peace. And they wish that the United States, which god fathered the Good Friday deal, would take an active role in its preservation.

They know from personal experience the ugliness that awaits Ireland if the accord fails.

They are Eisenhower Exchange fellows — part of a program that brings emerging leaders from abroad to meet their American contemporaries. They include fellows from a 1989 “Island of Ireland” group that brought Protestants and Catholics from British-ruled Northern Ireland together with citizens of the Republic of Ireland in the south — at a time when cross-border and inter sectarian meetings were rare.

They include 14 emerging Irish leaders, professors, politicians, civil servants, and other professionals who will have to cope with the dangerous mess Brexit is creating.

These fellows talk about the madness of rebuilding nationalist walls that the EU helped tear down.

David Lavery, one of the 1989 group, was a government lawyer in Belfast who had “very little contact with the Republic" before becoming a fellow. The 300-mile border between north and south was guarded by British soldiers, and watchtowers, while the IRA (Irish Republican army) battled British soldiers and Protestant unionist paramilitaries.

“My best friend in university was murdered in 1979 [during “the Troubles],” he recalls. Working for a law firm, his friend was serving a policeman with a document in a troubled Republican area. As he left the police station, he was mistaken for an officer in civilian dress and was shot dead by an IRA activist. “As he fell from his motorcycle, they shot him again on the ground,” Lavery said.

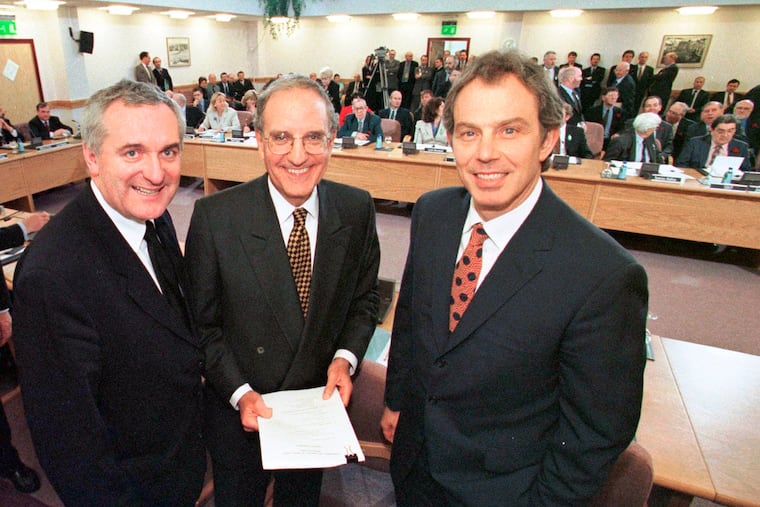

After 1989, Lavery had many cross-border meetings with his Eisenhower Exchange colleagues from the Republic, including Patrick “Paddy” Teahon. Lavory wound up on the British government negotiating team in 1996, while Teahon was on the Republic of Ireland team, working for the taoiseach (prime minister). “I met Paddy when the teams met for the first time, and the benefits of the fellowship kicked in,” Lavery says. “We had a bit of trust.”

Ultimately those talks — with stellar Clinton administration help — produced the Good Friday Agreement, giving the north self-government and opening the border with the south.

However, and this is key, the fact that Great Britain and Ireland were both in the European Union facilitated that open border, with no customs checks or barriers. “People starting going up and down to shop for a day, bring the kids,” recalls 1989 fellow Joyce O’Connor, an education leader from the republic. “People could live on one side and work on the other.”

“The animosity was going down, road services [between north and south] increased,” recalls prominent Presbyterian minister John Dunlop, a 1989 fellow from the north.

Then came the 2016 Brexit referendum in Britain, and parliament’s paralysis. If Britain “crashes out” of the EU, while the Republic of Ireland remains in, the border between the north and south of the Irish island would be reinstated. “All the momentum we had generated, we’ve lost that in the past two years,” Dunlop says.

This prospect has already sent tensions flaring in Northern Ireland, as the leading Protestant party agitates for Brexit and Catholics oppose it.

“Brexit has been an awful experience,” says Teahon. “It has created this space where dissident Republicans renewed the view that there should be a united Ireland." Violence has returned, and a leading young journalist, Lyra McKee, was recently shot dead in Derry in a clash between radical Catholic youths and police.

“We see the creation of fear again,” says O’Connor. “There is no certainty.”

For Dunlop, these dismal prospects make it critical that civic leaders, like the 2014 crop of fellows, work to make their voices heard. Like Katy Hayward, a Queens College Belfast expert on Brexit, who told me, “EU membership made it all possible, the benefits to Ireland after the Good Friday Agreement.”

And Sonja Hyland, the Irish ambassador to Ethiopia, who rightly complained: “It is hard to accept that [the issue of the Irish border] isn’t relevant to so many in Westminster [the British parliament].” Indeed, hard-line Brexiteers, like former U.K. Foreign Minister Boris Johnson, have sneered at the border issue.

The message I heard from these Irish civic leaders was clear: The restoration of borders within Ireland would be a disaster. And American political leadership, so critical to producing the Good Friday Agreement, would be most welcome in saving it.

The fellows applauded U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi for visiting Ireland and declaring that any Brexit deal must honor the Good Friday Agreement. (President Trump, unfortunately, is a Brexit cheerleader, but perhaps a visit to Ireland could enlighten him.)

As they gather in Philadelphia, the Eisenhower Exchange fellows will all be wrestling with the conundrum of how to keep the border open and the Irish peace alive.