Philadelphia’s many African students need culturally inclusive education | Opinion

Africans are misrepresented and underrepresented in American media. Culturally sensitive lessons connected to students of African immigrant roots would reverse many of these biases.

Immigrants are a force in Philadelphia, but their educational needs are neglected. As of 2016, Philadelphia’s immigrant population had increased by 69 percent since 2000, accounting for more than 232,000 residents. An estimated 1 in 4 children in the city immigrated themselves or were born to immigrants, and Philadelphia’s labor force has about 1 in 5 immigrants. Africans make up the fastest-growing segment of this immigrant population, yet belong to a marginalized group.

In the School District of Philadelphia, immigrants and native-born students of African backgrounds rarely see themselves reflected in curricula. What message does this absence of their people, their histories, their cultures send to children? “You don’t belong — Philadelphia isn’t your city, America isn’t your country.” Students of African immigrant backgrounds endure bullying for being African, “too black,” or speaking English with an accent. Historically in America, Africans have been viewed through a stereotypical lens of wildlife and backwardness. These perceptions persist and continue to hurt Philadelphia children. A recent University of California study found that Africans are misrepresented and underrepresented in American media. Culturally sensitive lessons connected to students of African immigrant roots would reverse many of these biases.

As the founder of African Community Learning Program, I regularly witness the power of culturally inclusive education. In the 2016-2017 school year, around 1 in 10 of Philadelphia’s more than 130,000 students were English-language learners. Many of these students struggle to learn, and culture can serve as their entry point. For example, in our program, we assigned students to write about their day during a weekend. A newly-arrived student from Mauritania wrote in French. With support, he translated and edited the draft in English, practiced reading the work aloud, and presented his story during our Africa Celebration. We assume that every student comes to us with knowledge rooted in their experiences and cultures. Starting from their knowledge base, we teach students how to read, write, comprehend, and speak English. Because culture informs people’s being, it must be central to children’s learning processes.

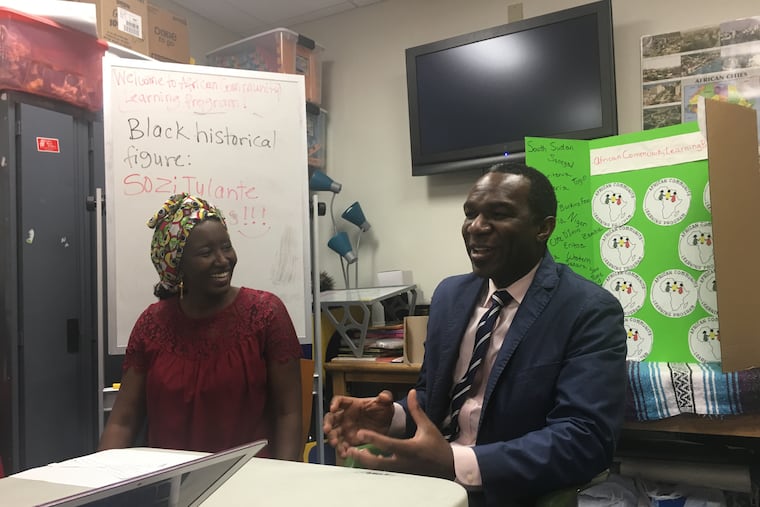

An inclusive curriculum also broadens children’s perspectives and gives them hope for the future. For Black History Month, we are learning about eight historical people of African immigrant heritage, one of whom is Sozi Tulante, Penn Law professor and former Philadelphia city solicitor. During his talk, Sozi answered questions about his studies at Harvard, career in law and government, and his struggles adapting to American culture, including facing rejection because of his African identity. Our students learned about Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), Sozi’s native country, and listened to his story of struggle and progress. After Sozi’s talk, one student from Senegal said, “I learned that people like me can go very far in this country.” Education should provide children hope for their futures, accompanied by support to achieve in school and life.

Centering education in children’s cultures means acknowledging their humanity. As scholar and educator Omiunota Ukpokodu writes in her book You Can’t Teach Us if You Don’t Know Us and Care about Us: “If we humanize our students, then we must know them, and if we know them, then we must care about them, and if we care about them, we will do all that is necessary and humanly possible to teach them well and foster their academic and personal success.”

It’s time for the district to adapt more culturally inclusive curricula to help students with African immigrant roots feel welcome and engaged in their learning, and to expand the worldviews of their peers of other heritages.

Aminata Sy is founder and president of the African Community Learning Program, a 2019 Rangle International Graduate Fellow, a multimedia journalist, and a senior at the University of Pennsylvania, where she studies international relations and English. She is also founder, editor, and publisher of the #500EmpoweringAfricanStories Project.