My childhood was so tinged with racism I couldn’t even recognize it | Opinion

I never even realized these incidents were hate crimes until well into my 20s.

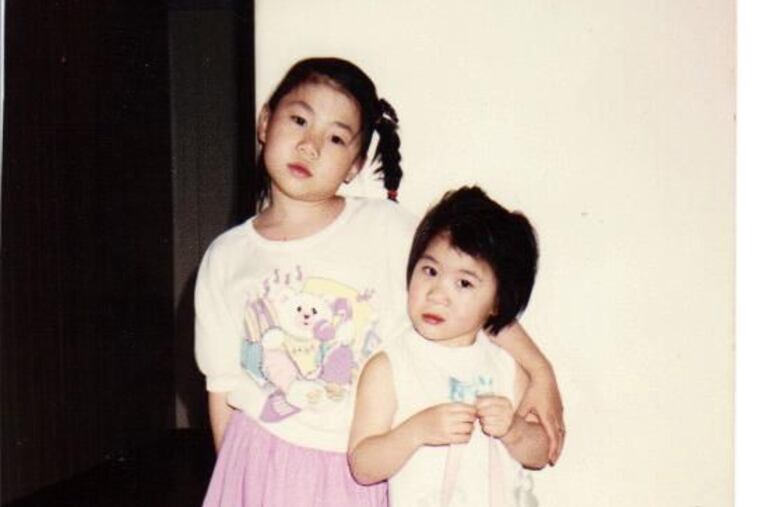

Some of my earliest childhood memories were acts of discrimination and racism.

I remember when my classmates slanted their eyes and sang at me in fake Chinese on the playground. I remember when their parents aggressively asked, “No, where are you really from?” as if “Philly” couldn’t possibly be an answer. I remember grown men on the street asked me “to love them long time” while leering at my pubescent body.

I remember my parents’ laundromat windows being smashed in, and the police officers that couldn’t be bothered to step out of their cars once they showed up at the scene and then saw our faces. My parents swept up the broken shards of glass and never brought it up again.

I remember when my sister’s car was keyed with the word Chink, when my parents were egged, robbed, and told to “go back to their country,” and all the times I was told that I ate dogs and carried disease.

» READ MORE: The ‘model minority’ stereotype simplifies Asian American stories like mine | Opinion

Yet I don’t remember a time I confided in anyone. Not a soul. I never even realized these incidents were hate crimes until well into my 20s.

I grew up in the 1990s in Philadelphia, and my family simply did not have a language for racism. I was never taught about microaggressions, white privilege, or institutionalized racism. All I knew was the constant feeling of discomfort, insecurity, and threat, but never understanding why.

This was further undermined by peers and adults, who gaslit my emotions by stating “it was all a joke” or calling my tears “overly sensitive.” Teachers, bus drivers, and my peers’ parents, who often witnessed others openly screaming racial slurs and taunts, never said a word. These adults colluded to instill an atmosphere of silence and indifference.

I accepted this racism because I didn’t know any different. This was my normal. I truly never understood that I as a person — my culture, my language, and my community — deserved to be respected.

A significant reason why I lacked the language was I didn’t know the history of my people. Only when I began to read more about Black Americans’ history and struggle for equal rights did the lightbulb turn on. I realized that what happened and is still happening to communities of color is not right. Only then did I gradually begin to connect my own experiences to America’s long history of colonialism and occupation in Asia, unconstitutional legal sanctions, internments, mob lynchings, and genocide of Asian communities and other communities of color.

Based on many U.S. textbooks, history seems to have forgotten. For that reason, anti-Asian crimes, like those against my parents — and like the recent Atlanta mass shootings — are often incorrectly treated as isolated robberies, random assaults, or civil disputes rather than hate crimes.

The culture of conformity and immigrant vulnerability perpetuated my parents’ silence. It drove the shame of being targeted, the desire to avoid confrontation, the traumatic detachment, as well as a healthy mistrust of law enforcement, who could be as dismissive and hostile as our attackers.

My parents also believed that if we assimilated with those around us, we could achieve success. We didn’t realize whole systems were invested in seeing our communities fail. When microaggressions and hate crimes occurred, we dealt with it by working harder to assimilate. I internalized a sense that I don’t matter and what happens to me doesn’t matter. Even as I write this now, there is a part of me that questions, “Why would anyone care?”

» READ MORE: What I want to tell my kids about racism as a South Asian American mom | Opinion

But after a year of witnessing escalating anti-Asian violence, I found myself sobbing and burdened by sleepless nights. It has re-triggered decades of pain and humiliation. I suddenly realized how little I processed a lifetime of trauma.

Then, I chose what previously felt unthinkable: I shared my story with others on social media. The childhood taunts, the fetishization, the vandalism, the assaults, the glares during COVID lockdown, the three eggings of my house, one on Lunar New Year’s Eve. After the Atlanta shootings, I saw other people speaking out about their experiences for the first time, sharing their all-too-familiar attacks, harassment, and fear. Despite being friends, we as a community had for so long suffered in individual isolation.

Our collective silence unknowingly reinforced the stereotype that we are white-adjacent because “bad things” don’t happen to us.

Our collective silence unknowingly reinforced the stereotype that we are white-adjacent, not in need of support or resources, because “bad things” don’t happen to us. People wonder why we are so “hysterical” because apparently anti-Asian racism only started a year ago. But they are finally questioning the validity of that narrative, which locked out AAPI communities from discussions on civil rights that extended to equal pay, prison reform, and school, workplace, and health-care protections. That narrative treats Asian communities as a monolith and shuts out the diaspora of diverse perspectives and needs.

Speaking out, and finally naming the hate we experience, is a revolutionary act — one I am proudly seeing more and more. It is difficult enough that the world outside AAPI communities colludes to maintain silence. We should not add to it ourselves. We deserve to be respected simply because we exist, not for what we can produce or offer. Our voices, demands, and concerns should be heard. Our hate crimes should be seen and charged as hate crimes. For the first time in my lifetime, I am joyously moved by the choir of voices leading this charge.

Becky M. Cheung holds a doctorate in clinical psychology, focusing on holistic well-being, diversity issues, and cognitive and educational evaluation.