When he couldn’t find words, he yelled: What aphasia looked like in my dad

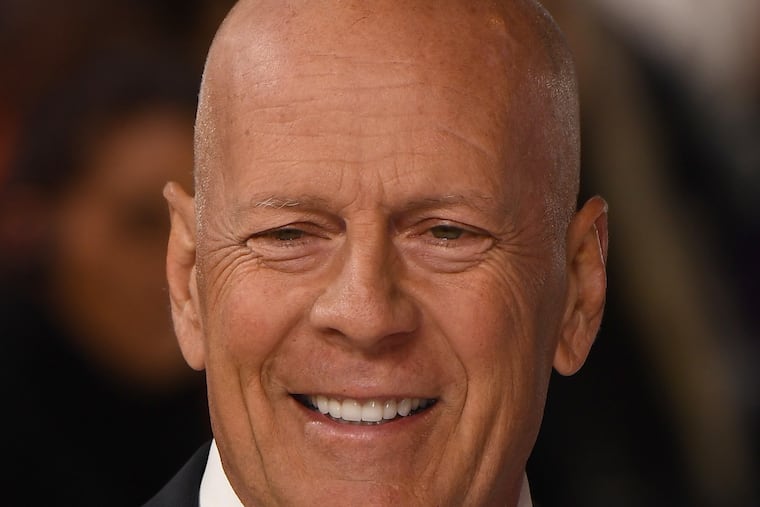

When I heard about Bruce Willis, I thought about his family. They may have a long road ahead.

I first noticed something was different about my father on a phone call. It was about 10 years ago, during one of our check-ins, when he couldn’t find a word he wanted to say. This wasn’t the usual “whatchamacallit” that everyone has now and then; it was different.

Later, in person, sitting across from each other in the living room of his house in Wyndmoor that felt so empty after my mother died, he tried to stutter out a word he wanted, then gave up, slapping his knee in frustration.

A bubble of worry formed in my belly. “Dad, what’s going on?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he said, shaking his head.

Soon after, he and I learned a new word: aphasia, a condition where people have trouble saying or understanding words. You may have learned it recently, too, as Bruce Willis’ family just announced his diagnosis.

When I heard about Willis, I instantly thought about my dad. Then I thought about Willis’ family. Because aphasia is hard on the person with the diagnosis, and on those who love them.

Aphasia affects around one million people in the U.S.; most develop it after a stroke, but it can also result from a brain tumor or brain injury. In my dad’s case, it was the first sign of a form of dementia. My dad started losing a word here and there, then over the next 10 years lost everything else.

As an only child, I was my father’s primary caregiver. And since I knew him best, when he began to struggle more to speak, I became his primary translator. In my 30s, as my friends were throwing themselves into careers, getting promotions and raises, I could only take part-time work so I could bring my dad to the doctor, the store, and wherever else he needed to go.

Then one day, several years after his diagnosis, none of my tricks — suggesting words he might be looking for, prompting him to describe the meaning instead — worked. And with that, my dad was cut off from most of the world.

He stayed home more, silently watching other people talk on TV. And when he couldn’t find words, he would bellow in frustration the one word he never lost: “No!”

I used to think of my father as a gentle giant (he was 6-foot-5), but the affable man who used to love making people laugh started scaring my toddler and the many nurses’ aides I paid to try to interpret his needs.

There was one bright light in his routine: the Aphasia Center at Moss Rehab in Elkins Park, which hosted a support group for people with aphasia. Sharon Antonucci, who directs the Aphasia Center, told me on Thursday that she’s always impressed by the creative ways people with aphasia learn to communicate. She’s known some who write poetry instead of speaking. One man who used to be a designer would communicate by sketching detailed pictures of his life. “He was drawing on a strength that was unique to him,” she said.

But my dad didn’t have those kinds of strengths to draw on. As his mind deteriorated, he lost the ability to understand the world around him, including how to answer the phone, change the channel on the TV, and dress himself. And the worse he got, the more I started forgetting about what he used to be able to do and say, as if my subconscious wanted to protect me from memories that would make me too sad.

Ned McCook died in September 2020, and at his funeral, I didn’t have many words to say about him. I couldn’t remember his endless jokes, and all the adages he had drilled into my head over the years that are only now coming back to me (“You don’t ask, you don’t get” and “There’s no such thing as a free cat”).

As an actor, Bruce Willis is immortalized by his work, which included words that became his signature (you know the phrase from Die Hard). So the best of him can never be forgotten, which I hope provides some comfort for his daughters.

I was lucky in a lot of ways because no matter how much my dad forgot, he almost always knew who I was; he would smile and reach for me whenever I walked into his room. And I’ll never forget the last word he said to me.

It was on one of our weekly video calls during the pandemic, in the summer of 2020, when I couldn’t visit him at his nursing home. As I was blathering endlessly to fill the silence on the iPad one of the nurses had propped up in front of him, talking about the day I would be able to come see him again, I asked if he would like that.

Out of his usual quiet, one word emerged, crystal clear: “Very.”

The memory of that moment, and that word, makes me happy. And very sad.

Alison McCook is The Inquirer’s assistant opinion editor.