Baltimore County schools shut down after a cyberattack. The same could happen in Philly. | Opinion

What if colleges with advanced cybersecurity expertise were to step up to protect Philadelphia and other schools from cyberattacks?

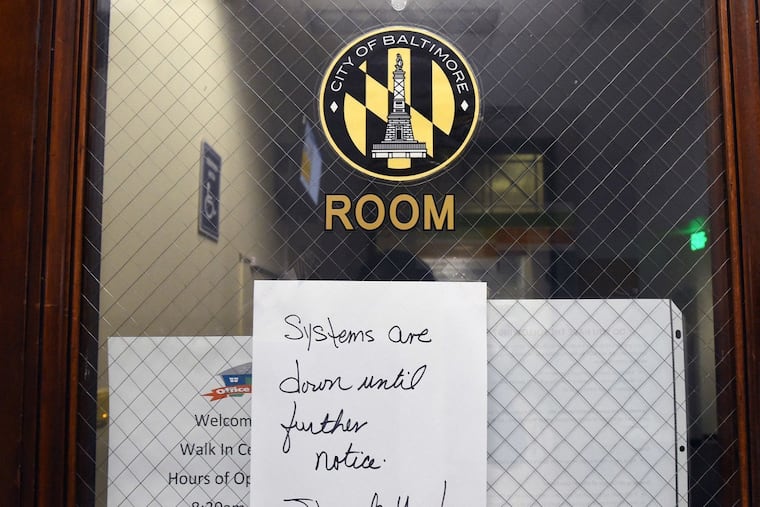

The day before Thanksgiving, the Baltimore County School District learned the hard way to prioritize cybersecurity. Attackers inserted malicious software in their systems—ransomware, in cyberspeak—then threatened to block access or publish data unless the district paid a ransom. It closed County schools (surrounding the city of Baltimore, which has its own school system) for two days on Nov. 30 and Dec. 1.

The K-12 Cyber Security Resource Center reports more than 1,000 cybersecurity-related incidents in U.S. schools since 2016. That includes an attack this June, when the University of California San Francisco paid about $1.14 million to release data from its medical school that the hackers were holding hostage, and one that stalled the network in Montgomery County’s Souderton Area School District last fall.

How did we get into this mess? In April, the FBI warned that online lawbreakers were taking advantage of the public’s dependence on virtual environments during the pandemic. A Maryland state audit released the day before Baltimore County’s cyber attack identified “significant risks” within the school system’s computer network.

» READ MORE: Cities like Philadelphia are sitting ducks for cyber attacks | Opinion

Clearly school administrators weren’t equipped to guard against this threat. If tested, many of the nation’s more than 131,000 K-12 schools in Philadelphia and elsewhere would earn failing grades in cybersecurity. Until they experience a breach, administrators often cannot fully understand the nature of this problem. It takes time, diligence, and repeated practice to become security proficient in our virtual world. And insecure online classes weaken entire systems.

One easy remedy many fail to follow, for example, is installing free security patches for their operating systems as recommended by developers like Microsoft. The shift to online learning has exposed these kinds of lapses from educational institutions. More data, more young online users, and weak security are a goldmine for nefarious actors.

But there’s a fairly straightforward partnership that could tackle the problem. What if colleges with advanced cybersecurity expertise were to step up to help stop the epidemic of cyberattacks?

Public schools could provide these university-level programs with a real-world clinic for practical learning. Local teams of university experts—students supervised by professors—could assess and bring their skills to the cyber integrity of the nation’s 1,000 school districts and recommend improvements. Consultant teams could also help design curricula on cybersecurity in each computer-equipped classroom, recommend ways to improve school cybersecurity protocols, troubleshoot when problems arise, and conduct webinars on security for students, parents and guardians. Everyone benefits.

» READ MORE: Philly hunger relief group Philabundance lost nearly $1 million in cyberattack

Baltimore County, for example, could have called upon Maryland’s 17 National Centers of Academic Excellence in Cybersecurity, a program whose mission is to create and manage a collaborative cybersecurity educational program with community colleges, colleges, and universities. In the Philadelphia region, several cybersecurity programs encourage hands-on learning: Drexel University’s Cybersecurity Institute, Temple University’s Professional Science Master’s in Cyber Defense and Information Assurance, and La Salle University’s Master of Science. Statewide, Hewlett Packard Enterprise’s top 10 rankings for the best schools for cybersecurity include Carnegie Mellon, the University of Pittsburgh, and the West Chester University of Pennsylvania.

One criterion for the HP rankings is a learning environment where students and faculty collaborate to address real-life cybersecurity threats. Professor Giovanni Vincenti, Applied Information Technology program director at the University of Baltimore and consultant in online learning, says collaborations are key and, with advance planning, may have long-term merit. He already encourages his cybersecurity students to tackle real-world challenges both as a learning tool and to help society. He supervises a team of University of Baltimore students working on NASA SUITS, a challenge for students to design and create spacesuit information displays in augmented reality environments.

Professor Vincenti’s observations of student teamwork bodes well for other applications in public schools: “No matter what, they will stay on the project until they have results.” There’s no reason other cybersecurity talent can’t apply that mentality to help local schools keep their systems safe.

» READ MORE: Ransomware attacks are hitting local governments. Here’s how they can fight back.

It would be a waste, and a gamble, to miss the teachable moment from the rise of ransomware attacks. Integrating cybersecurity into education is essential for current and future generations. Children are vulnerable from the moment they create their first password. It’s incumbent on educators and parents to teach them early on to protect themselves and the computer systems they access. Baltimore’s attack is sure to have successors. Teaching kids and their families about online security from the first keystroke can minimize the costs of cyberattacks and the invasions of privacy.

UNICEF says that each day 175,000 children go online for the first time. With numbers like this, offering a new model for teaching young people how to navigate the virtual world is as necessary as learning your ABCs.

Heidi Boghosian is an attorney and author of the forthcoming “I Have Nothing to Hide” and 20 Other Myths about Surveillance and Privacy (Beacon Press).