Why are there so few Black American players in MLB 74 years after Jackie Robinson took the field? | Opinion

The crux of the issue comes down to money and where Major League Baseball chooses to invest it.

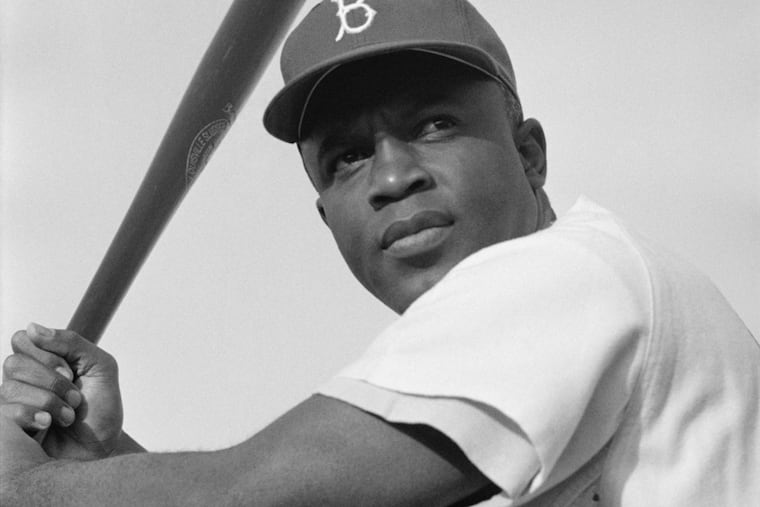

Seventy-four years ago, in 1947, the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Major League Baseball’s first African American player in the modern era: Jackie Roosevelt Robinson. This historic moment is celebrated as the formal “integration” of Major League Baseball (MLB). For three decades after Robinson broke the “color line,” there was a steady increase in American-born Black players taking the field. But this year, on opening day 2021, just 7% of players on MLB rosters are American-born Black athletes.

What has happened to the Black American baseball player?

Sportscasters, “talking heads,” and the person on the street often answer this question by perpetuating broad, sometimes negative, stereotypes, suggesting that young Black men don’t want to play baseball because it’s not as “flashy” as basketball, or because they don’t see people who look like them playing on the field.

» READ MORE: The Phillies Opening Day 2021 roster

Our research demonstrates that, in fact, it is structural factors that provide a more nuanced answer to the question — and the crux of the issue comes down to money and where the MLB chooses to invest it.

The rise of the academy system in the Caribbean and South America during the 1980s, and a shift in the pipeline to the major leagues for native-born players in the 1990s, altered the demographic makeup of MLB players. As a result, a new MLB emerged. This MLB featured fewer American-born Black players. It relied on the recruitment, extraction, and exploitation of foreign-born Latino players and American-born parents’ wealth to cultivate their sons’ talent through showcase events, private coaches, or sports academies like IMG Academy.

Thus, we can no longer say that baseball is part of the American Dream. Major League Baseball is a story of the haves and the have-nots; it is a story of the colony and the country club.

The ‘colony’ of the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic is rich in baseball talent. In 1987, the Los Angeles Dodgers became the first team to establish a baseball academy, Campo Las Palmas, and by 2003, every MLB team had an academy in the Dominican Republic. As a result, American baseball treats the country like a colony providing the “good” of baseball talent without offering anything meaningful for the country in return, with the end goal of moving players and the money they earn over to the United States.

The ‘country club’ of IMG

The mid-1990s marks the explosion of sports academies in cultivating American-born talent for professional sports. And, though there are camps for basketball and football, the focus has always been on the country club sports: tennis, golf, soccer, and increasingly, baseball.

Academies like IMG may not be intentionally excluding Black American athletes, but the demographic data from IMG tell a story of exclusion. The student-athlete body at IMG is 35% international, 31% white, and only 7% Black. Elite academies may simply be “out of reach” for the majority of Black families, who have, on average, only one-tenth the wealth of the average white family. Interestingly, the percent of Black athletes at IMG Academy mirrors the percent of Black players in MLB.

Academies have displaced Little League fields and AAU leagues as the pathway to a college scholarship, and consequently, the pipeline to MLB for American-born players.

Major League Baseball may not have intentionally closed the door on the sport that Jackie Robinson so greatly loved, but intentionally or unintentionally, that’s exactly what has happened for American-born Black players.

» READ MORE: Five things to know as the Phillies welcome fans back to Citizens Bank Park

At the heart of the matter is money. MLB invests tremendous financial resources into building the human, social, and cultural capital of players born outside the U.S., particularly in the Caribbean and Latin America, that it does not invest in low-income Black (and white) players in the United States.

Similarly, at the institutional level, an underlying problem is the underfunding of the majority of college baseball programs. This leaves baseball programs in a pickle; they are reliant on recruiting only those players whose families can contribute to their son’s tuition, which few families can afford, even less so Black families. They are also vulnerable to scams like the “Operation Varsity Blues” scandal that rocked higher education.

If MLB is invested in equality and diversity, as their proclamations of Black Lives Matter suggest they are, the course can be reversed. But this will involve significant change and forging new and different collaborations. The first step is building a navigable, accessible pathway for Black players to the MLB.

Earl Smith is currently an adjunct professor in women and gender studies and the associate of arts program at the University of Delaware and emeritus distinguished professor at Wake Forest University. Marissa Kiss earned her doctorate in sociology at George Mason University. Her dissertation, “Baseball: The (Inter) National Past time,” examined immigrant Major League Baseball players and immigration policy.