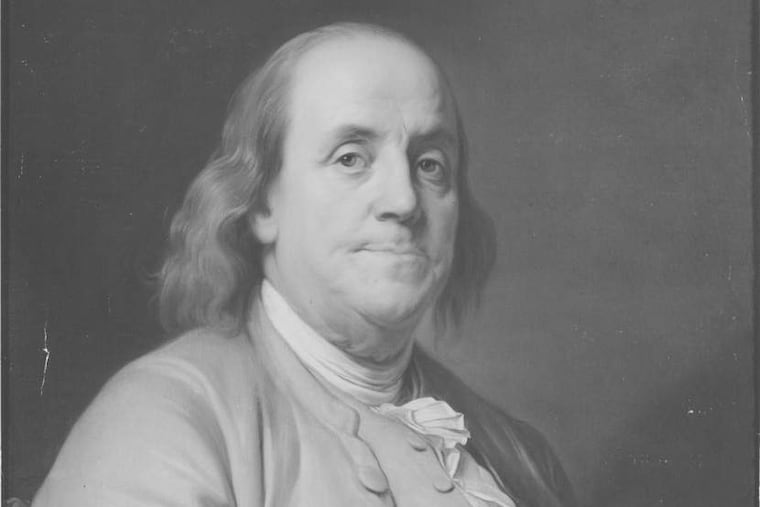

Ben Franklin: 4 things that made him great

Sure, there's the bifocals, the diplomacy, the timeless aphorisms. But what made Franklin great was his personality.

Last month, Benjamin Franklin would have turned 317.

Franklin has become a “classic” — a person we honor by calling them great while forgetting what really makes them great. It is possible, in Franklin’s case, we remember lightning (which he connected to electricity), bifocals (which he invented, along with several other inventions still in use today), and maybe recall a few of his humorous aphorisms (“haste makes waste”). He founded the first library, the first hospital in America, a fire department, the University of Pennsylvania, the American Philosophical Society, insurance companies, and established the U.S. Post Office. Plus, he was a politician, diplomat, and author. His list of accomplishments is breathtaking.

But those things — as worthy as they are — are not what makes him great.

I always thought it was more than coincidence that he was born at the start of the year — precisely the time when we are making (or already breaking) — our New Year’s resolutions. Because I believe the most remarkable thing about Franklin is his wisdom on making meaningful resolutions to help us grow and lead a better life.

His greatness stemmed from four characteristics, all related.

When Franklin returned to Philadelphia from nearly 10 years as ambassador to France, he was 79 years old, and within months launched a major house addition. What type of man undertakes a building project at 79?

But that renovation speaks to who he was, as it included a library to fit his roughly 4,000 books, evidence of his endless curiosity. He was always learning about the world, how it worked — and pondering harder to explain things that did not seem to make sense and how he could make it better. It was this curiosity as to why travel to England was so much faster than the return that led him to delineate the Gulf Stream, a current of warm surface water that flows from the east coast of the U.S. to Europe. It was his curiosity that allowed him to propose lead as a common factor causing health problems among painters, plumbers, and other professions that work with lead — long before the rest of the world figured out the dangers of lead poisoning. It was his curiosity that made him conduct his experiments to uncover so much about electricity.

But Franklin was not a solitary genius — he was a social being. He sent and received more than 15,000 letters in his lifetime, and his civic improvements were always undertaken with others. His house renovation included a dining room to seat 24 people. It was the site of critical dinners to plot strategy by attendees of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, such as James Madison.

“Franklin was not a solitary genius — he was a social being.”

A third Franklin characteristic that drove his greatness was a craving for open discussion and carefully listening to and deeply respecting the views of others. In September 1787, at the final session of the Constitutional Convention, Franklin gave a speech, in which he stated: “… the older I grow the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others.”

Finally, Franklin embodies the trait of personal — especially moral — growth. From early on, he recognized he was not perfect, made mistakes, and needed to improve. He kept a “moral diary” critically assessing his progress on 13 virtues. In his autobiography, he identifies errata — things he did in his life that he regretted and wished he could improve upon.

» READ MORE: Ken Burns on Ben Franklin’s legacy: It’s complicated | Opinion

Consider, for instance, his position on slavery. Like many white men at that time, he owned multiple slaves. But in 1763, Franklin went to a school for Black children and witnessed, as he said, that the intellectual capacity of Black children was equal to that of white children, and stopped owning slaves. In the last few decades of his life, he became a fierce critic of slavery. He condemned people for using sugar that was drenched in the blood of slaves. In his will, he required his son-in-law to free his slaves. Just weeks before he died, he penned a scathing takedown of slaveholders’ justifications for slavery. Franklin agreed to become the president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and submitted the very first petition to the first Congress demanding an end to slavery. It was his last public act.

Franklin was great precisely because through his curiosity, his openness to the views of other people, and his dedication to constantly growing, he could listen, learn, and try to improve himself until his dying day.

Ezekiel Emanuel is the vice provost for global initiatives at the University of Pennsylvania. He teaches an online course on Ben Franklin.