We can teach Black kids to read and love who they are. Here’s how.

Let's bring back the "porch lessons" that supplemented Black children’s schooling in the ‘60s, which were designed by Philly pioneers.

In the 1960s, many Black preschoolers in Philadelphia were armed with literacy thanks to Freedom Schools teachers in West Philly, part of a national movement created in that era to supplement the inadequate education many Black students were receiving.

Along with institutions of the South and brick-and-mortar schools like Freedom Library Day School, the Freedom Schools launched highly effective “porch lessons.” These home-learning sessions were organized by Black families who knew all too well what Maya Angelou would later memorialize: “Elimination of illiteracy is as serious an issue to our history as the abolition of slavery.”

Now, more than five decades later, the literacy crisis — particularly for Black and other marginalized children — has only worsened, exacerbated by the further eradication of Black educators from the teaching corps.

» READ MORE: Pa. principals are quitting in record numbers, and I know why | Opinion

The latest public school student achievement outcomes should keep us all up at night.

Only 38% of our children in Philadelphia are reading at grade level in elementary school, and only 7% of our teachers nationwide are African American, while more than twice that percentage of students are Black. Research shows there’s a connection.

Black teachers help all children, but especially Black children, do better in school, making it more likely they will graduate high school and enroll in college. They also mirror and empower a proud racial identity and historically accurate cultural worldviews.

This past May, the nation observed the 70th anniversary of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education. Although desegregation nominally sought to integrate students, it also resulted in forcibly removing highly qualified Black educators from the classroom.

In losing Black teachers, we didn’t lose just their significant influence; we lost their pedagogy — or teaching strategies — which collectively went unrecognized, unused, unstudied, and unreplicated.

Let’s help bring back Black pedagogy by turning to the lessons learned from the Freedom Schools of yesteryear.

The porch lessons that supplemented Black children’s schooling in the ‘60s were designed by Philly pioneers, including educator-activist Suzette Abdul-Hakim. The preschoolers, who were considered young scholars, were shown how to pronounce each letter sound with mouth formations and tongue placements. They practiced breaking down, building, and blending sounds, words, and sentences. At every point, their racial identity, culture, and worldviews were reflected and affirmed, even without realizing it.

Often anti-Blackness is taught subversively; for instance, by using only books that feature white characters. But the children under the auspices of Freedom Schools learned about who they were and the world around them both implicitly and explicitly. They read stories together, connecting their lives with those of the ancestors whose achievements they were taught to cherish and build upon.

This was done so consistently, seamlessly, and thoroughly through guest lectures, books, songs, poetry, and more that it’s difficult for many of the children to recall the first time they were taught about Malcolm X, Kwame Nkrumah, Benjamin Banneker, Bobby Seale, Angela Davis, Queen Nanny, and a host of others in their canon.

The children witnessed, as they benefited directly from, their families’ sense of urgency for Black literacy and insistence on communal accountability, building motivation and direction for the activist and leadership roles they each were expected to assume in the ongoing fight for racial equity and social justice.

Pedagogy is a word fraught with ignorance. Add Black in front of it, and Black pedagogy becomes all the more incomprehensible, if not intimidating, even among well-established educators. Yet, all students (perhaps, most critically, those studying to be future educators) would benefit from teaching strategies that help students uphold their cultural identities, which empower children both intellectually and socially, as researcher and educator Gloria Ladson-Billings has noted.

Pedagogy is a word fraught with ignorance.

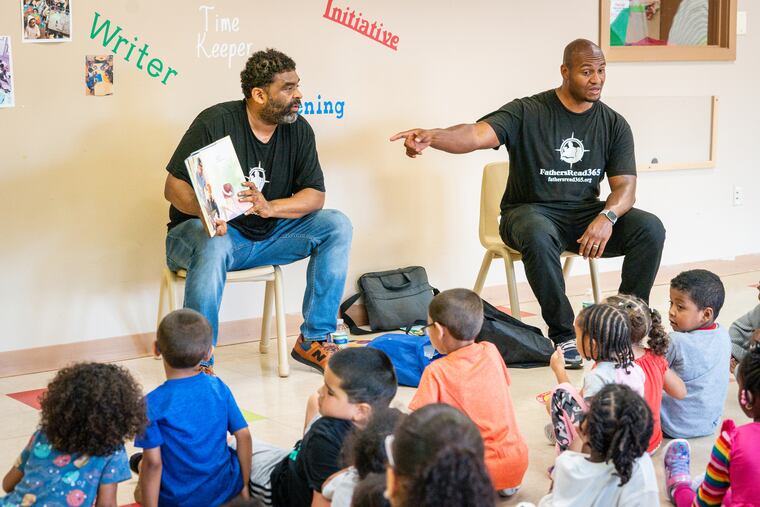

There are many ways to offer culturally relevant pedagogy, from creating Black-centered, intergenerational, intellectually rigorous learning spaces that are loving and inclusive, designed for scholars to fall in love with themselves and with learning, to cultivating supportive and connected relationships so that scholars benefit from teachers within and beyond their classrooms.

A product that evolved from such pedagogy is the “Freedom Schools Alphabet Song” that our organizations are bringing back through the Right2ReadPhilly campaign. The song goes beyond the alphabet song we all know by helping children match letters with the sounds they make. Instead of singing individual letter names (“A-B-C”), students sing a sound each makes (“Ah-Buh-Kuh”) to encourage reading by sounding out letters and words.

The song’s ties to Black pedagogy, and the need for more of it, are clear. First created by Black teachers and Black families of the Freedom Schools movement, the “Freedom Schools Alphabet Song” was designed — along with many other educational enrichments — to provide marginalized communities with a way to address schooling inequities (that still persist).

It was and is promoted today to be an intergenerational family and community affair, with grandparents, older siblings, parents, and neighborhood reading advocates actively participating in growing strong readers. The song showcases Black teaching traditions, including call-and-response learning and representations of Black joy and excellence.

There are countless other ways we each can exercise playful learning with our children in ensuring, as award-winning education activist and influencer Chris Stewart first coined, that “the revolution will be literate.”

To protect all our children’s right to read, we must not impede the agency of our families, rightfully seeing them as the educational partners they are, and welcome Black teaching strategies back into classrooms, on neighborhood porches, and at dinner tables.

After all, we each have a role — and a stake — in advancing the literacy revolution.

Sharif El-Mekki, a Freedom Schools alum and lifelong educator and “Freedom Friday” podcast member, is the founder/CEO of the Center for Black Educator Development, whose mission is to rebuild the national Black teacher pipeline, heralding a simple, powerful message from students: We need Black teachers. Heseung Song is a Harvard-trained developmental psychologist and president/CEO of Mighty Engine, the agency facilitating the Right2ReadPhilly campaign.