Black music is about more than entertainment. It’s a first draft of history.

People often talk about “the sound of Philadelphia.” The sound of Philadelphia is the sound of Black music.

There was a place outside in Washington Square known as Congo Square, where free and enslaved Black people would gather to sing and dance to the music of West African cultures. Bandleader, composer, and Philly native Francis Johnson performed across the United States and was the first Black musician to tour Europe with a band in the 1800s. Soon after, he was followed by singer Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, who also lived in Philadelphia.

The flood of Black music out of Philadelphia continued into the 1900s, as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker improvised bebop at the Down Beat on South 11th Street, Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff founded Philadelphia International Records, and the Roots played hip-hop on South Street.

People often talk about “the sound of Philadelphia.” The sound of Philadelphia is the sound of Black music. It’s the sound of summer block parties in North and West Philly, as neighbors beat the heat to the joyful sound of classic soul and funk.

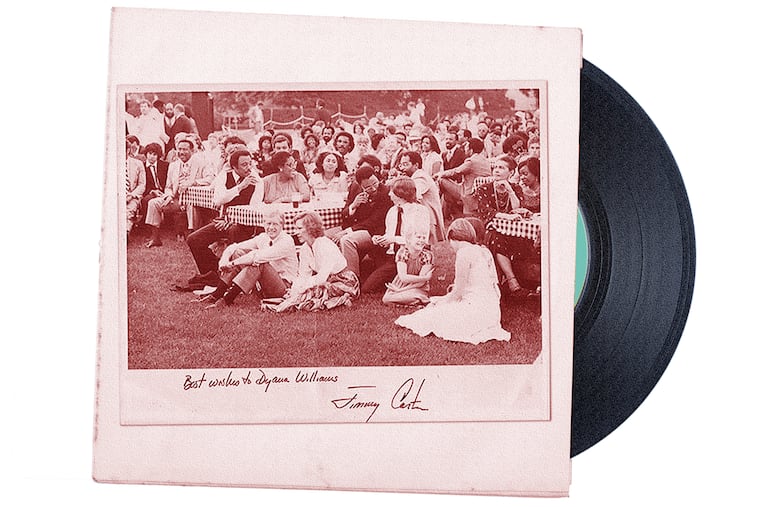

So it is no coincidence that the seed for Black Music Month — celebrated in June — was planted by two local icons, songwriter-producer Gamble and celebrity coach Dyana Williams, along with Cleveland DJ Ed Wright. Together, they formed the Black Music Association to “preserve, protect and perpetuate black music.”

On June 7, 1979, President Jimmy Carter declared the first Black Music Month at a White House buffet supper and concert.

In his remarks, President Carter said, “If we had had a Black Music Association organized 203 years ago, so that Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson and George Washington could have heard some of this music at the very beginning, our country could have avoided a lot of trouble, a lot of heartache, and a lot of struggle, and a lot of suffering, and a lot of division, and would be even greater than it is now.”

He’s right: Black music is about more than just entertainment. It tells the story of Black people, and the history of this nation, both good and bad.

Black music is about more than just entertainment.

Williams, affectionately called the “mother of Black Music Month,” agrees. In a recent direct message to one of us (Anderson) on Twitter, she wrote: “From the birth of America, all genres of Black music, from spirituals to hip-hop, are our unique indigenous art forms. Black music is at the very root of our influential culture in the United States, but also impactful around the world. Black music is a meaningful creative expression that documents Black people’s presence in America.”

Since “coming to the land of liberty” on a slave ship, Black music has been a form of resistance, rebellion, and resilience. Negro spirituals such as “Go Down, Moses” and “Wade in the Water” helped guide the self-emancipated to freedom. “No More Auction Block for Me” and “Steal Away” put a lie to the myth of the “happy slave.” Billie Holiday protested lynching in “Strange Fruit,” which was released in 1939. Folk and blues pioneer Lead Belly denounced racial segregation in “Jim Crow Blues.”

Blacks and whites mingled to jazz in “black and tan” nightclubs during the swing era. The Down Beat, the first racially integrated nightclub in Center City, was forced to close after repeated police harassment.

In remarks to the 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. observed that jazz was a stepping stone to the civil rights movement: “Much of the power of our Freedom Movement in the United States has come from this music. It has strengthened us with its sweet rhythms when courage began to fail. It has calmed us with its rich harmonies when spirits were down.”

Since 2000, every president has issued a proclamation designating June as Black Music Month. In his 2023 proclamation, President Joe Biden said, “Today, the creative ways that Black music tells stories of trial and triumph in American life continue to move us all to understand the common struggles of humanity.”

As with Carter’s 1979 concert, President Biden’s Black Music Month/Juneteenth concert presented several genres of Black music: spirituals, gospel, the blues, R&B, rock and roll, jazz, pop, and rap. It was great to see.

But apart from the White House, celebrations are increasingly focused on the fruit, not the roots from which Black music sprang. This, to us, is a missed opportunity. While hip-hop is today’s popular music, its drum beats are the fruit of a tree with deep roots.

» READ MORE: Philly: Black rock capital of the world?

The two of us grew up in different generations and different socioeconomic circumstances, but we share an appreciation for Black music. Back in the day, we were exposed to diverse styles of Black music on the radio, jukeboxes, television variety shows, and in school. For Anderson, it was Donald Byrd’s “Cristo Redentor,” Nina Simone’s “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” and B.B. King’s “Why I Sing the Blues.” For Spivak, it was Ella Fitzgerald’s “A-Tisket, A-Tasket,” Count Basie and Joe Williams’ “Every Day I Have the Blues,” and Etta James’ “Something’s Got a Hold on Me.”

As Johnny Gill would say, “my, my, my,” how times have changed.

Today, radio is largely a vast wasteland of programming based on algorithms. With the elimination of music education in public schools, there are few opportunities for children to be exposed to Black music history. With the teaching of African American history under attack, a month dedicated to Black music should be intentional in telling the full story.

Black music history matters. As Marcus Garvey, founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, said, “A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.” Black music has always been more than entertainment. From the “sorrow songs” of the enslaved to the protest songs of the Black Lives Matter movement, Black music is a first draft of history.

Faye Anderson is the director of All That Philly Jazz, a place-based public history project that is documenting and contextualizing Philadelphia’s golden age of jazz. andersonatlarge@gmail.com

Herb Spivak co-owned two of Philadelphia’s legendary jazz clubs, the Showboat and Bijou Café. He was a cofounder of the original Electric Factory and Electric Factory Concerts.