Should local election boards be nonpartisan? | Pro/Con

The Inquirer asked City Commissioner Omar Sabir and independent poll worker Ryan Godfrey to debate: Should Philly’s election workers be nonpartisan?

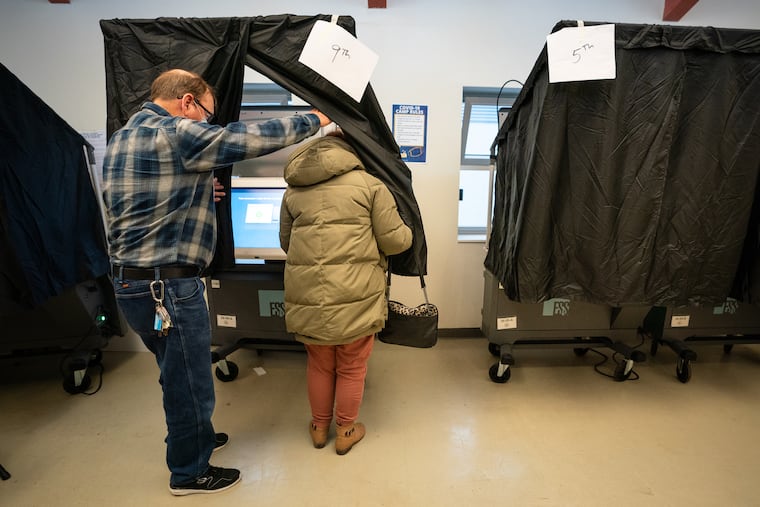

Running for your local election board is one way to help your neighborhood and city make sure our elections remain fair and free. Pennsylvania elects its local election workers every four years and will do so again in 2021. Seats are open for a judge of election and two inspectors in each of Philadelphia’s 1,700-plus voting divisions. Many of these seats go unfilled every cycle and require appointments. If you want to run for judge or inspector of election as a Democrat or Republican, the time is now to make it happen. Nomination petitions need to be filed with the county board of elections by March 9, and then you’ll be on the ballot for the May 18 primary, potentially competing against others in your party for the right to appear on the general election ballot in November.

But with an increasing number of voters registering as independent or unaffiliated, some wonder if the people administering our elections should be nonpartisan as well. The Inquirer asked City Commissioner Omar Sabir and independent poll worker Ryan Godfrey to debate: Should Philly’s election workers be nonpartisan?

Yes: Bipartisan election boards tend to become unipartisan.

By Ryan Godfrey

Running for your local election board is an important way to give back to your community and to help your neighborhood and city make sure our elections remain fair and free. The “normal” approach to winning a seat in Pennsylvania is to run in the primary, either as a Democrat or a Republican, and then if you win, get your name on the general election ballot.

But there’s another, rarely used, way to get elected as a local poll worker. Independents and members of minor parties (that is, anyone not a Democrat or a Republican) do not have to face off in the primary at all. Unaffiliated and minor-party voters running for judge or inspector of election can get their names directly onto the November ballot by circulating nomination papers starting March 10.

What’s the downside of bypassing the primary in this way? There’s only one: You can’t be a Democrat or a Republican, or you need to leave your party by April 18. This means not voting for people in primary elections (though you can still vote for primary ballot measures) as long as Pennsylvania maintains its closed primary system.

“The ranks of the politically unattached have expanded to the point that there are now thousands more independent and third-party voters registered in Philadelphia than there are Republicans.”

But what about the upside? Philadelphia is a city where only one current major officeholder, Councilmember Kendra Brooks of the Working Families Party, has won office outside of the traditional Democratic/Republican paradigm, despite voter rolls that have surged with unaffiliated and third-party voters in recent years. After decades of political irrelevance in a city mostly powered by partisan machinery, the ranks of the politically unattached have expanded to the point that there are now thousands more independent and third-party voters registered in Philadelphia than there are Republicans. Who represents them in office? Just Councilmember Brooks and (by my count) about five of the city’s thousands of elected inspectors and judges of election. Those numbers have nowhere to go but up.

Philadelphia is a city of neighborhoods, and increasingly, like most of the United States, the people we live near tend to share our political ideals and priorities. This can make it hard in practice to satisfy the ostensible goal of the well-intentioned but antiquated state law of having bipartisan local boards. If we ignore the growing reserves of unaffiliated voters, there often simply aren’t enough people willing to run as Republicans (or Democrats in the pockets of the city where the partisan polarity is reversed) to fill out the elected positions. When no one runs, the positions have to be filled by appointments. Bipartisan election boards then tend to become decidedly unipartisan.

Most states and localities do not elect their poll workers; Pennsylvania has been an outlier in this respect for decades. It’s always been true — but especially following the contentiousness and (unfounded) accusations of cheating in the presidential election — that the last place we should expect partisanship is from the people running our elections at the neighborhood level. One timely way to lessen the impact of the designed-to-be-partisan structure of our state and city’s election system is for civic-minded citizens to run and serve outside the constraints of the two-party system. Local election boards are an ideal place to do just that.

Ryan Godfrey is a software engineer. He has served as an inspector or judge of election in Cedar Park since 2013.

No: Bipartisan local election boards maintain a sense of trust for their constituents.

By Omar Sabir

Bipartisan election boards are vital to overseeing fair elections that people can trust.

Not every state has partisan poll workers, but in Pennsylvania, they guarantee that both political parties are overseeing the electoral process occurring in every polling location and that proper procedures are adhered to. This is especially true in a state with strong partisan traditions and organizations.

Much of the commonwealth’s election law embraces this history, including the 67 bipartisan boards of election that oversee elections in every county. Regulations do vary in other states where independent or nonpartisan poll workers run election precincts, but the bipartisan oversight we have in Pennsylvania bolsters institutionalized trust and good communication between observers of the election and its constituents.

One may theorize that nonpartisan or independent poll workers will cooperate seamlessly with each other, but polling place by polling place, this may not be the case. Even poll workers who are technically unaffiliated with a political party may have viewpoints or interests that are in conflict. All the better to have poll workers who administer the election in a nonpartisan manner but also be clear about who is overseeing the process from each side.

You can even see how this plays out in specific voting procedures our poll workers administer. The provisional ballot, for example, is a critical safeguard to make sure no registered voter is disenfranchised. And to complete such a ballot, both the judge of election (of the major party) and the minority inspector (of a nonmajority party) must sign an affidavit, along with the voter.

“Building trust through partisan poll workers is more important to stem the spread of misinformation about how our elections work.”

It is also important that poll workers run on a partisan basis so that voters have some basic understanding of their candidacy. The absence of party labels can confuse voters and make it difficult for them to choose among candidates they may not know. How are they supposed to distinguish between multiple individuals listed at the bottom of their ballot and running to be a poll worker? Ideally, a voter recognizes their neighbor and believes that they would be up for the job. But absent that personal connection, a voter may instead depend on any cue that is available, which could be the ethnicity of a candidate or whether the candidate is listed first or last.

Bipartisan local election boards maintain a sense of trust, integrity, and voice for their constituents. Nine out of 10 voters are partisan in Philadelphia. Having bipartisan election boards gives them the opportunity to feel safe and understood. Their voice as a community can be heard regarding their grievances and concerns. This works well in Philadelphia where we have 66 wards, each of which is divided into divisions starting from 11 to 51 (each with its own polling place), a total of 1,703. With up to six poll workers per division, we have literally thousands of community members who are part of the processes.

And especially in recent years, building trust through partisan poll workers is more important to stem the spread of misinformation about how our elections work. Well-trained staff and a well-trained, bipartisan election board is a key defense to misinformation and to voter disenfranchisement.

Omar Sabir is one of Philly’s city commissioners, tasked with overseeing elections.