5 years since the COVID lockdown, can we talk about what we’ve learned?

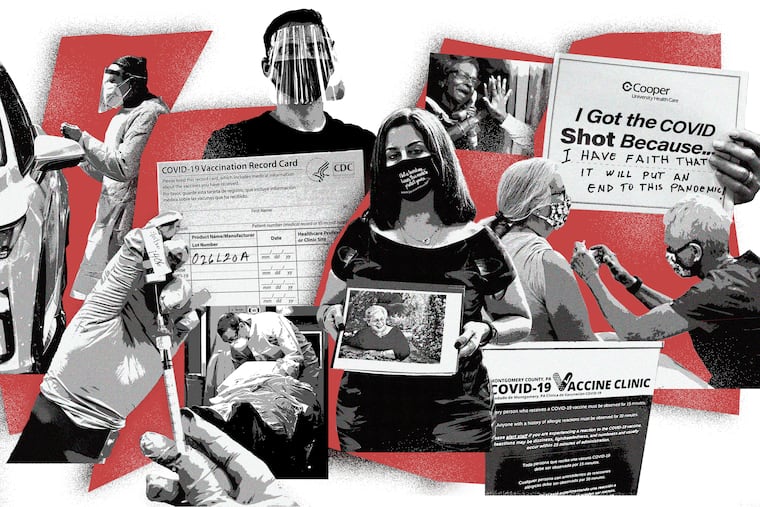

The narratives that have grown around pandemic lockdowns have increasingly supplanted any tales of the ingenuity, dedication, and compassion of frontline health-care workers.

Five years ago last week, the coronavirus lockdowns began. Like so many others who were working in health care at the time, I remember the long hours, the nervous energy, how anxious and exhausted we all were. But those of us caring for the sick in hospitals were so busy that much of it is hazy now. Occasionally, I‘ll remember a few details when my colleagues remind me of specific situations. I never imagined it would be something I could ever forget, but that is the way memory works — you remember a few key moments and then develop narratives around them.

One in 300 people have died of the disease in the United States. At its peak in winter 2020, twice as many people died each day of COVID-19 than in the 9/11 attacks, yet no public memorial or robust national conversation about the pandemic exists.

I like spring: the lengthening days, the icy air slightly warming, and the buds sprouting on plants. It was spring when the lockdowns started. My colleagues — fellow intensive care unit physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, and countless other clinicians — did not stay home.

In the face of a virus that would ravage the world (leading to close to 15 million deaths over two years), we went to work.

No treatment nor vaccine existed for the first waves of COVID cases, and it was unclear whether we would come home to our families. In fact, more than 100,000 health-care workers died in the first two years.

At work, we hastily turned medical floors and postoperative care units into medical intensive care units. The fields of home science, mechanical engineering, and medicine overlapped as we fiddled to create devices to keep our team safe.

Potentially lifesaving interventions — like the intubation box made of plexiglass and plywood we would put over the heads of patients in order to stop the spread of the virus when they needed to go on the ventilator — make me chuckle now (it was useless), but the risk from aerosol spread of the virus was deadly real when we cobbled it together.

My wife was pregnant with our third child in the spring of 2020. I not only feared for my own well-being but for my family’s and the unborn baby’s.

An unlimited number of heroic tales of the sacrifices made by health-care professionals exist — like a physician not being able to embrace his newborn for months, or a perfusionist (an expert in the heart and lung machine used during COVID to help save people’s lives) sleeping at the hospital during the whole first wave because they feared infecting their loved ones.

Remember, science cannot be exact when dealing with a new and evolving health threat like COVID-19. We tried to do our best with the knowledge we had at the time, and for too many, that wasn’t good enough.

But the lockdowns were lifesavers, stopping hospital systems from being overwhelmed, leaving enough medical-grade oxygen and ventilators for everyone to be treated. We lacked treatments, but the lockdowns gave us time.

The unintended consequences of the lockdown — extreme social isolation, educational and economic disruptions, and the escalation of violence — were a public health failure, and unfortunately, the narratives that have grown around those aspects of the pandemic lockdown have increasingly supplanted any narratives about the ingenuity, dedication, and compassion of frontline health-care workers.

As one of those who worked in the trenches, I don’t believe defunding science or not treating global disease is the appropriate reaction to the difficulties we confronted during the pandemic lockdowns.

Disease knows no boundaries. For example, in the past, the United States has intervened in West Africa to halt Ebola outbreaks, thereby preventing that highly contagious virus from becoming a widespread global crisis.

Being a frontline health-care provider responding to diseases like COVID or Ebola is scary, and as the measles upsurge and vicious influenza season has recently reminded us, concerns about highly infectious viral outbreaks aren’t limited to other continents.

Five years on, the political and emotional consequences of the COVID pandemic have altered all of our lives — and not always for the better.

However, there are some positive takeaways:

Vaccines work and save lives.

Your nurses, physicians, and respiratory therapists will be there when you need us.

And we are here today, able to reflect on how that moment has led us to where we are.

Nitin Puri is an associate professor of medicine at Cooper Medical School of Rowan University. The opinions expressed in this essay do not necessarily reflect those of Rowan University or Cooper Medical School.