Lack of internet access holds immigrant communities back | Opinion

Language barriers, migration patterns, and fear on the part of undocumented families of signing up for service can block families from online access.

I finally made the difficult decision to flee the violence of my war-torn homeland of Syria when I realized that there was no longer hope of building a future there for my wife, son, and parents. It was a difficult road to get where I am today. The process of applying for refugee resettlement in the United States is extremely rigorous and drawn out. I know how lucky we are to be here in a place where people look out for one another, a place built on connections.

As we see an educational system that is transitioning more online, that support needs to extend to tackling the digital divide—and how it holds back immigrant communities. With resources increasingly available, we must work to ensure that all people find their path to that connection.

For centuries, immigrants to this country have availed themselves of the educational opportunities the U.S. offers to build better lives for themselves and brighter futures for their children. Access to education is critical to those futures.

» READ MORE: Why Internet access is a ‘super’ determinant of health | Expert Opinion

I should know. I was a teacher in my home country, but, as with many professions, my overseas certification turned out not to be valid in America. I found a way to continue my life’s work of helping others by working at the Nationalities Services Center (NSC) here in Philadelphia, where I have served as the Job Development Coordinator for the past four years. While I’m no longer in a classroom, I still work to connect with people and provide them knowledge and tools to improve their lives.

In this role, and at home, I’ve seen that accessing quality, affordable internet is essential, especially during the COVID pandemic.

When the pandemic forced my son’s schooling to an online format, I was able to help him set it up and navigate his various classes. But not as many immigrant children were so fortunate. Nonwhite Hispanic Americans lag White Americans in internet adoption by 8%, although the gap has been closing. There are a number of reasons for this, including language barriers, migration patterns, and fear on the part of undocumented families of signing up for service.

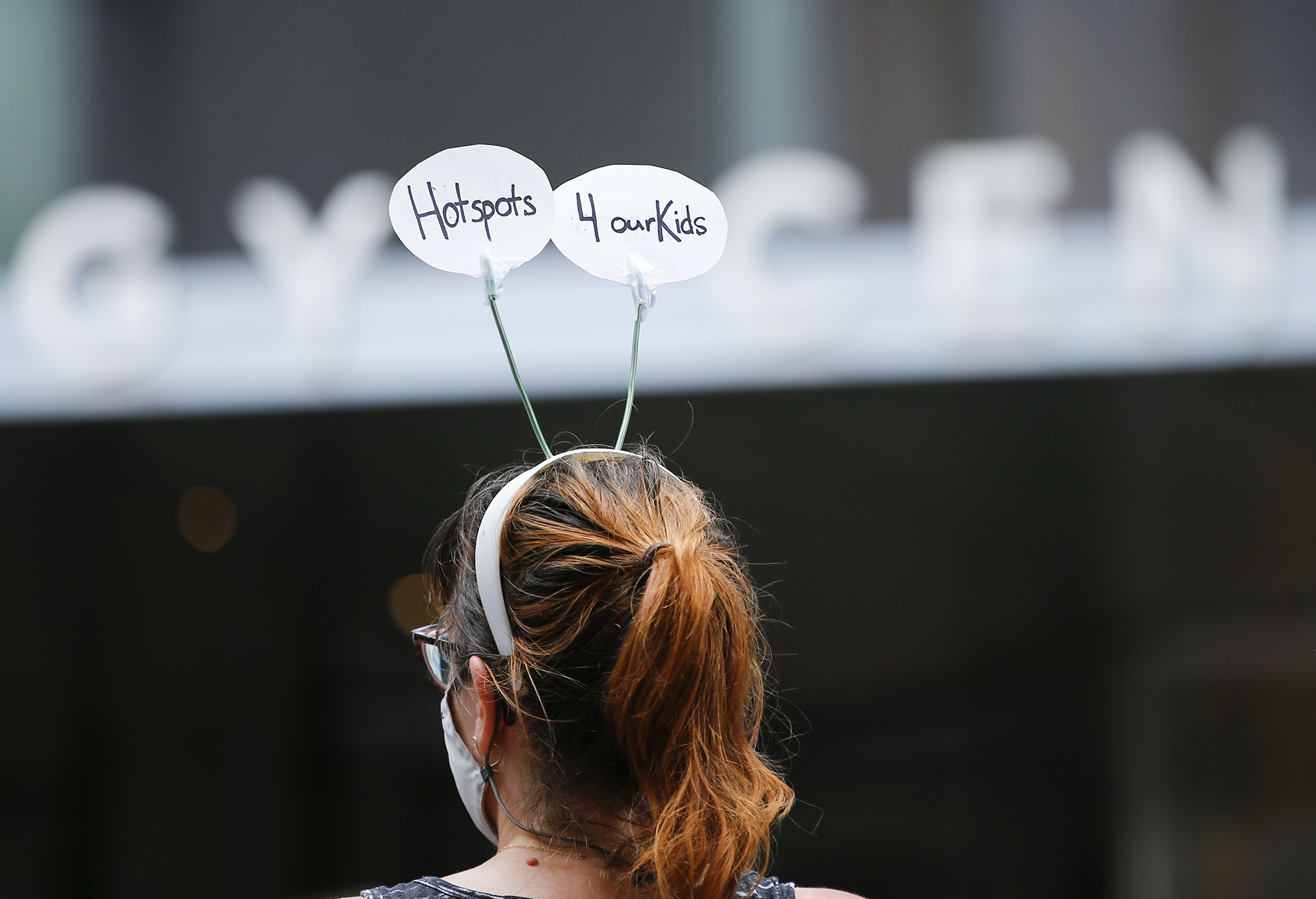

When the Philadelphia School District announced that public school students would not return to classrooms until mid-November earliest, I worried that immigrant youth – already facing multiple barriers to equity and inclusion – would fall farther behind.

Some of my worries were assuaged when the City, School District and a number of philanthropic and business partners announced their “PHLConnectED” initiative to link 35,000 low-income families – including many of the immigrant youth I serve – to free broadband services. These students will be connected to the internet via Comcast’s Internet Essentials program, the service my family signed up for when we first arrived and which we still rely on to this day.

While I applaud this effort, providing free internet is only the first step. Now we have to make sure every student properly receives this service. This means Philadelphians stepping out of our siloes and getting creative in identifying families who lack internet service. It also means understanding why these families may not have signed up for internet prior to this, like language barriers and lack of digital literacy that go well beyond cost.

» READ MORE: Philly promises public school students will have internet access as coronavirus keeps classes online

At NSC, we work with the School District’s Immigrant and Refugee Education Collaborative, a group that includes government agencies, non-profits, and student advocates to solve the multi-faceted, complex challenges facing families. In addition to addressing the digital divide, the group has spearheaded efforts to ensure the needs of limited English proficient students and parents are met this fall by, for example, launching a community hotline and facilitating parent info sessions in different languages.

We will continue to work with this group throughout the rest of the summer and into the beginning of the school year to make sure the internet adoption rate among immigrant students is high, and that the students understand the technology they’re tasked with using.

These are the type of collaborative groups who will need a role in the digital learning process to ensure that the most vulnerable children among us are honored their right to better themselves through education.

By working together, we can deliver a brighter future for all of our children—just like the one I envision for my son.

Nasr Sadar is a Syrian refugee and currently employed as a Job Development Coordinator at the Nationalities Services Center.